Tricking your brain into saving

Lesson 1

Most families currently rely on whatever money is left over after covering expenses, but this “residual saving” isn’t always enough to fall back on in tough times.

A good rule of thumb is to have three to six months’ worth of living expenses saved as a financial safety net to manage unexpected costs or a sudden loss of income. However, not many families have an adequate buffer in place. Whether it’s job loss, a medical emergency, or a major home repair, these burdens can quickly become overwhelming.

On average, across countries, around two-thirds of households have less than three months’ worth of savings, leaving many vulnerable to unexpected expenses, such as job loss, medical emergencies, or urgent home repairs.

Saving money isn’t easy. It demands deliberate effort and long-term planning for uncertain future financial needs demanding a future-oriented mindset. Also, it often feels like a punishment as we restrain ourselves from spending, reducing both current purchasing power and immediate pleasures. This makes saving emotionally disconnected and negatively perceived because while the effort to accumulate wealth for the future goes unnoticed, the loss of spending power is felt immediately. In short, saving feels like a sacrifice—giving up some of today’s purchasing power for a future benefit we can’t yet see. This sacrifice feels burdensome, which often leads people to avoid saving altogether.

On the contrary, spending satisfies our impulses and current needs. It’s a more automatic and natural behaviour—if we want something, we buy it. Spending is present-oriented, requiring little planning. It’s emotionally rewarding because gratification is immediate. Spending also taps into our positive emotions, fulfilling desires for the things we want now.

For instance, buying a dress or pair of shoes is an almost automatic decision. We go to the shop, select the item, and make the purchase. Spending is present-focused, offering instant gratification. In contrast, saving for that same item demands patience and restraint, delaying the reward. While spending delivers immediate pleasure, saving feels like a slower, more uncertain process—a sacrifice for future benefits.

Secondly, when it comes to saving, many of us fall into a trap we’re often not even aware of: overoptimism. We know we should be setting money aside for the future, but the way we think about our future financial situation is often clouded by this overconfidence, leading us to both overspend by indulging ourselves and to delay or avoid saving altogether.

We tend to be overoptimistic about our future income, expenses, or opportunities. We’ve all been there—telling ourselves that while saving might be difficult now, it will be much easier in the future when we’re earning more money. Maybe you’re expecting a promotion at work, or you assume your career will naturally progress, bringing larger pay checks and more disposable income. Similarly, we tend to downplay the likelihood of future financial challenges, imagining our future as smooth sailing, where unexpected expenses, rising inflation, or job loss are unlikely to happen to us. Finally, this overoptimism can manifest in the belief that, somewhere down the line, good things will come our way, allowing us to hit our savings targets all at once.

But life rarely unfolds as predictably as we imagine. Promotions and raises might not come as quickly as expected, and life events like marriage or having children may increase expenditures, and unforeseen circumstances like medical bills, home repairs, or a sudden drop in income can significantly strain finances.

Optimistic expectations lead to a form of overconfidence that, instead of helping us build a savings buffer for unexpected expenditures, results in spending more freely. We tell ourselves we’ll "catch up" later when conditions improve. As a result, saving gets postponed, and the longer we wait, the harder it becomes to build a solid financial cushion. While it's natural to feel optimistic about the future, it’s essential to balance that optimism with a dose of realism. Rather than assuming that you’ll earn more, spend less, or stumble upon a lucky opportunity, it's better to take deliberate steps to save now.

Planning for saving and staying committed is challenging, as we need to overcome the feeling of sacrifice, adopt a forward-thinking perspective, and resist the emotional dissociation from immediate gratification. However, there is a method that can help us remain engaged in the process.

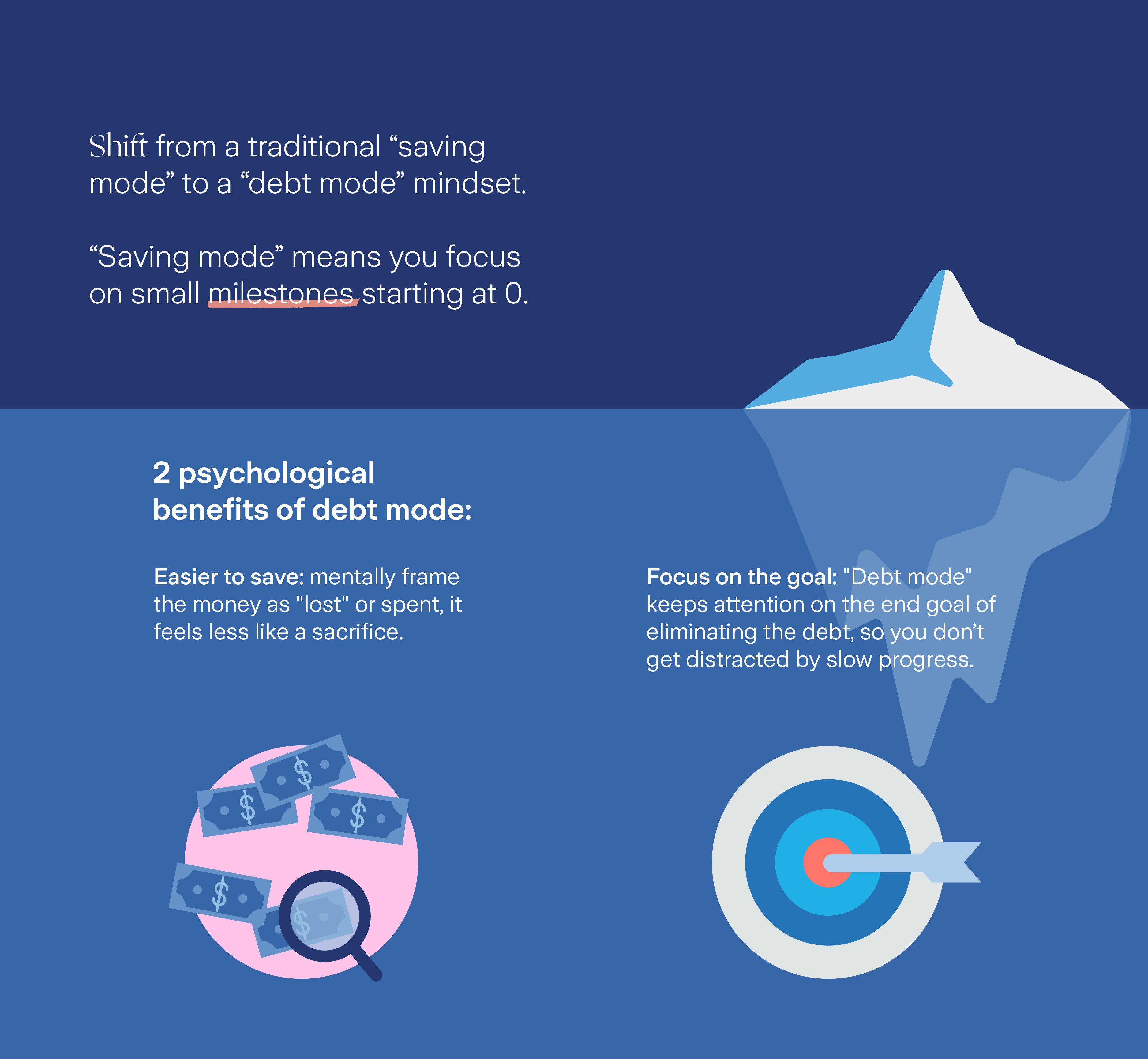

We often feel overwhelmed by the total amount we need to save to reach our goals. For example, saving $1,500 for home improvements can seem daunting. This is because we often take an accumulative approach, or "saving mode", where we measure progress by accumulating from zero to our target ($1,500). Since the reference point is 0, we need to save small amounts to perceive any progress. Moving from a 0 balance to some savings feels encouraging initially. However, paying $100 a month and reaching $500 after five months may not feel significant as well as making us lose focus on the ultimate goal of saving $1,500, leading to discouragement and quitting.

It might be more effective to adopt a decumulative approach, or "debt mode", where progress is measured by reducing the target ($1,500) to zero. The focus here is on moving from a large sum to a smaller amount. Imagine saving as if repaying a debt of $1,500, where saving becomes similar to debt repayment. Instead of accumulating, "debt mode" is about progressively reducing a substantial "debt." For example, paying $100 a month and going from -$1,500 to -$1,000 after five months may not seem like much, but the remaining debt still feels significant, which keeps us motivated to eliminate it. This way, we save while adopting a debt repayment mindset.

There are two key psychological aspects at play in "debt mode" that are missing in "saving mode":

1. We don't count on money we have already "lost", making it easier to set it aside.

Since saving involves a sacrifice and reduces our current purchasing power, we tend to avoid it. However, when we think of the money as already "lost" (as needed to repay a debt), we no longer rely on it for immediate needs. In "debt mode", we trick ourselves into believing that the money we’re saving is already spent or lost, making it easier to set it aside. Therefore, adopting this mindset doesn’t make us feel like we’re making a sacrifice. In our minds, the money is already gone, so saving feels less painful. On the contrary, we may even feel rewarded for repaying an "apparent" debt.

2. Focus on the final target instead of the growing balance.

In typical saving behaviour, we focus on the process and intermediate milestones, such as gradually accumulating towards a specific sum (e.g., $1,500). This approach can sometimes cause us to lose sight of the total amount we aim to save, as we become overly focused on the growing balance. If the balance seems sufficient, we may feel tempted to stop saving. In contrast, when repaying debt, our minds are more attuned to the total amount owed, as we measure progress by subtracting payments from the overall debt to reach a debt-free state. This end-goal focus helps maintain consistent motivation, as progress is tracked by reducing the total balance, rather than accumulating savings. By adopting this mindset for saving, we stay focused on achieving our final goal without getting discouraged by slow progress.

By applying this "debt mode" mindset to saving, you focus on the final goal and avoid getting discouraged by small gains. Moreover, you’ll stay focused on the target for longer, keeping motivated throughout the process. Finally, you won’t feel like you’re losing purchasing power, as the amount has already been mentally written off as lost.