In a world of increasingly dire climate warnings, can innovative science and engineering change the way we think about carbon?

Dr. Jennifer Holmgren, CEO of carbon capture recycling firm LanzaTech, thinks so.

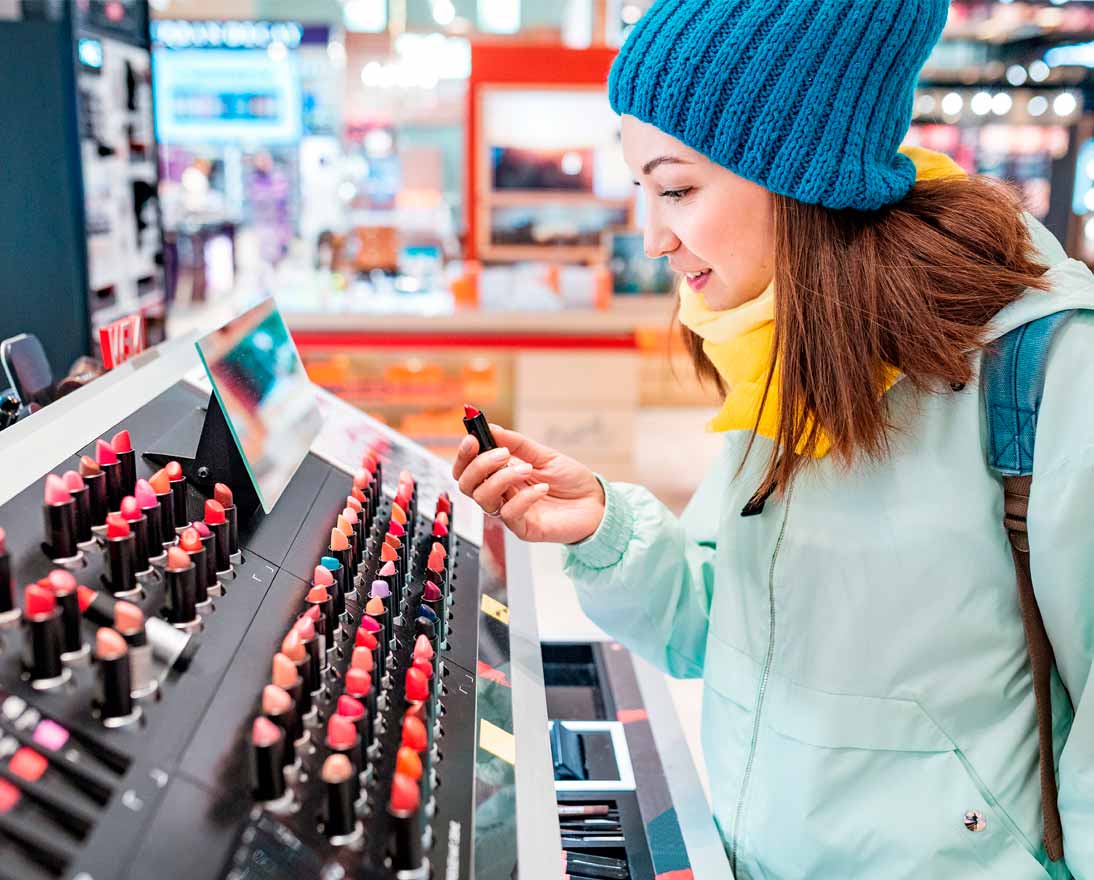

Nasdaq-listed LanzaTech, the company Holmgren leads, goes beyond simple carbon capture and storage by turning waste into everyday items. The company’s carbon recycling technology is already turning carbon waste into Zara party dresses, H&M workout gear, Bridgestone tires, sustainable aviation fuel and Coty fragrances.

The company was named one of TIME100’s most influential companies of 2023 and it was a finalist for The Earthshot Prize 2022, the environmental prize launched by Prince William.

LanzaTech uses rabbit-gut bacteria to ferment the waste gas from factories to generate ethanol. This process of microbial gas fermentation breaks down the waste into smaller chemical building blocks. Known as feedstocks, these can then be used to make new products.

“It's just like making beer, except instead of using sugar, we use gases,” Holmgren tells Bloomberg’s Francine Lacqua.

The company's method starts with waste input. This could be anything from household waste to carbon dioxide from an industrial steel mill. LanzaTech’s ability to recycle a wide range of waste from different sources makes it an attractive option in a world where carbon dioxide emissions are still rising and global waste generation is expected to grow by 70 percent by 2050. As Holmgren notes, the world is no closer to weaning itself off petroleum, and demand stands in the region of 100 million barrels every day. Technology that reduces fossil fuel reliance and emissions is much-needed.

LanzaTech is an example of the growing number of companies attempting to create a closed-loop or circular economy system, where waste is eradicated, and materials retain their highest utility and value. The company’s proprietary method can use every type of waste resource, making it particularly attractive for big emitters.

Not only can it reduce emissions, but it can create new revenue streams, reduce potential pollution penalties for companies, and allow firms to stay in business, protecting jobs at the same time. LanzaTech claims the carbon-reducing capacity of each plant is the equivalent of taking 120,000 cars off the road annually and has a payback period of as little as two years.

So far, so compelling. But could this technology delay the deployment of new green technologies by helping a steel mill or a refinery reduce its emissions today? The fourth plant built using LanzaTech’s method reduced the emissions produced by a Belgian steel mill by 3.9 million tons.

Holmgren bats away this line of questioning. “We're at the point where we just need to go fast. I don't think it's sensible to say, ‘we're going to shut down every steel mill right now and we're going to restart it using something that is less polluting’. That’s just not how the world works.”

“Every bit of carbon we prevent from going into the atmosphere is a massive win right now,” she says. Holmgren believes the technology offers hard-to-abate industries the chance to reduce their emissions while they develop their next-generation implementation. “I think we have to be careful not to let perfect be the enemy of good.”

To help it innovate faster, LanzaTech licenses its technology, allowing customers to build their own recycling plants near waste sources. Turning waste into materials for recycling cannot be done on a small scale. LanzaTech’s recycling plants are effectively like refineries, and each one costs in the region of $100 million to build.

By licensing the plant designs to their customers, they can scale faster without having to raise as much of the capital costs. To date, LanzaTech has four commercially operating plants, soon to be six. The company is aiming to have hundreds of plants built over the next decade, but Holmgren says that finding the finance to fund such ambitious expansion can be hard, even with the backing of the Earthshot Prize.

“You find that there's a lot of money for early-stage ideas,” Holmgren says. LanzaTech has already raised over $500 million, but scaling and innovating on multiple fronts rapidly requires a high level of investment. To get around this challenge, LanzaTech launched a separate spin-off called LanzaJet, to develop carbon recycling technology for airlines. It will open the world’s first and only ethanol to Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) plant in early 2024.

The momentum is there but breaking through with a disruptive idea takes a “tremendous effort,” Holmgren adds. “There are so many rules and regulations that become barriers to disruptive ideas. To me, that's the biggest challenge.”

LanzaTech is part of a growing number of companies working to address the world's growing carbon emissions. The science behind these companies is compelling, but good science alone won’t be enough. Challenges relating to scale, profitability and infrastructure must be overcome. But with a growing number of supporters, investors and partners, LanzaTech already has the momentum to match its ambition. It may have been shortlisted for the Earthshot prize, but it has its sights set on something even bigger.