The Global Risks Report 2017 Executive Summary

Global risksReportJanuary 17, 2018

For over a decade, The Global Risks Report has focused attention on the evolution of global risks and the deep interconnections between them. These trends came into sharp focus during 2016, with rising political discontent and disaffection evident in countries across the world. Read more here for the new outlook on the global risks landscape in 2017.

For over a decade, The Global Risks Report has focused attention on the evolution of global risks and the deep interconnections between them.

The Report has also highlighted the potential of persistent, long-term trends such as inequality and deepening social and political polarization to exacerbate risks associated with, for example, the weakness of the economic recovery and the speed of technological change. These trends came into sharp focus during 2016, with rising political discontent and disaffection evident in countries across the world. The highest-profile signs of disruption may have come in Western countries – with the United Kingdom’s vote to leave the European Union and President-elect Donald Trump’s victory in the US presidential election – but across the globe there is evidence of a growing backlash against elements of the domestic and international status quo.

The Global Risks Landscape

One of the key inputs to the analysis of The Global Risks Report is the Global Risks Perception Survey (GRPS), which brings together diverse perspectives from various age groups, countries and sectors: business, academia, civil society and government.

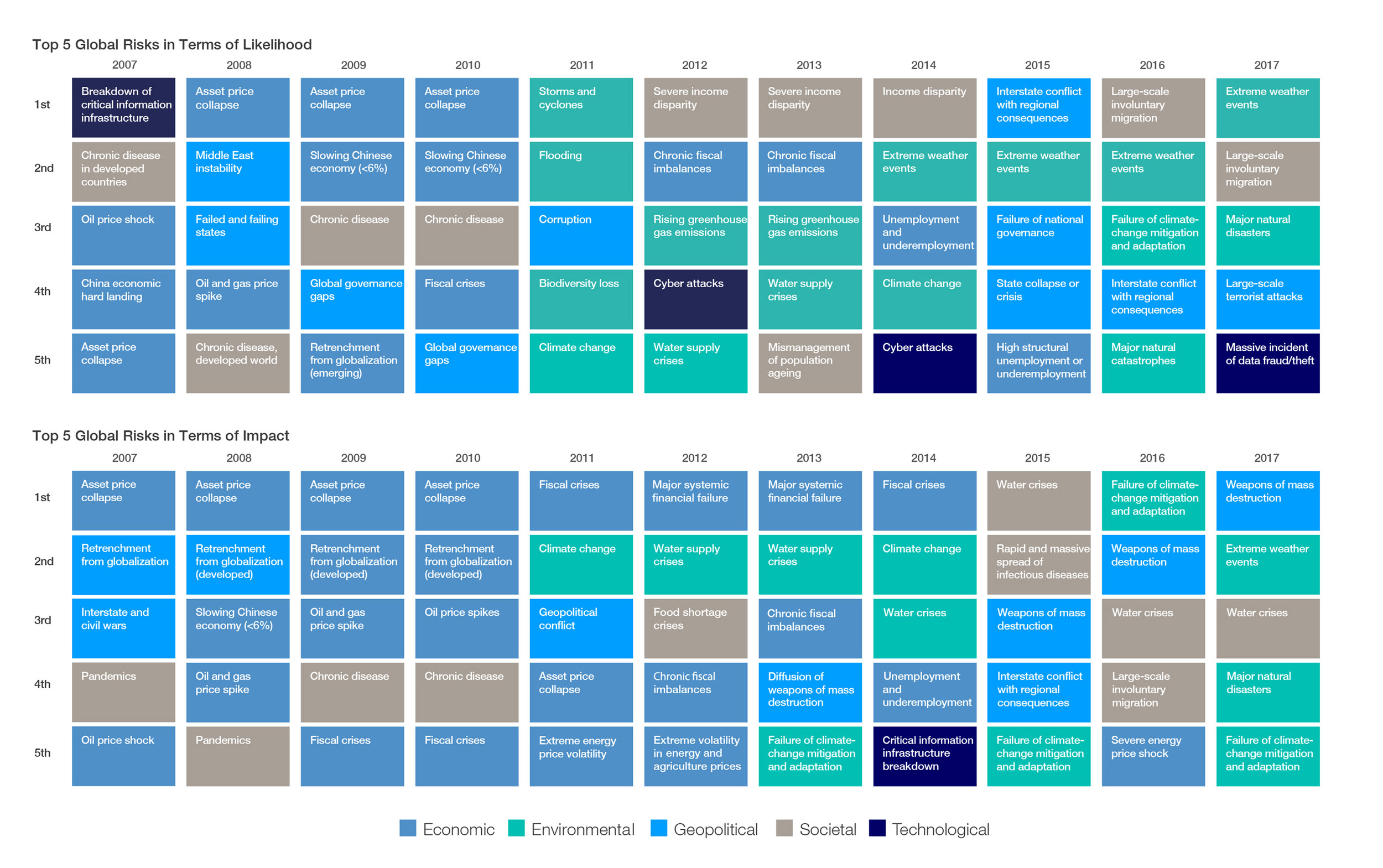

This year’s findings are testament to five key challenges that the world now faces. The first two are in the economic category, in line with the fact that rising income and wealth disparity is rated by GRPS respondents as the most important trend in determining global developments over the next 10 years. This points to the need for reviving economic growth, but the growing mood of anti-establishment populism suggests we may have passed the stage where this alone would remedy fractures in society: reforming market capitalism must also be added to the agenda.

With the electoral surprises of 2016 and the rise of once-fringe parties stressing national sovereignty and traditional values across Europe and beyond, the societal trends of increasing polarization and intensifying national sentiment are ranked among the top five. Hence the next challenge: facing up to the importance of identity and community. Rapid changes of attitudes in areas such as gender, sexual orientation, race, multiculturalism, environmental protection and international cooperation have led many voters – particularly the older and less-educated ones – to feel left behind in their own countries. The resulting cultural schisms are testing social and political cohesion and may amplify many other risks if not resolved.

Although anti-establishment politics tends to blame globalization for deteriorating domestic job prospects, evidence suggests that managing technological change is a more important challenge for labour markets. While innovation has historically created new kinds of jobs as well as destroying old kinds, this process may be slowing. It is no coincidence that challenges to social cohesion and policy-makers’ legitimacy are coinciding with a highly disruptive phase of technological change.

The fifth key challenge is to protect and strengthen our systems of global cooperation. Examples are mounting of states seeking to withdraw from various international cooperation mechanisms. A lasting shift in the global system from an outward-looking to a more inward-looking stance would be a highly disruptive development. In numerous areas – not least the ongoing crisis in Syria and the migration flows it has created – it is ever clearer how important global cooperation is on the interconnections that shape the risk landscape.

Further challenges requiring global cooperation are found in the environmental category, which this year stands out in the GRPS. Over the course of the past decade, a cluster of environment-related risks – notably extreme weather events and failure of climate change mitigation and adaptation as well as water crises – has emerged as a consistently central feature of the GRPS risk landscape, strongly interconnected with many other risks, such as conflict and migration. This year, environmental concerns are more prominent than ever, with all five risks in this category assessed as being above average for both impact and likelihood.

Source: World Economic Forum 2017-2017, Global Risks Reports

Social and Political Challenges

After the electoral shocks of the last year, many are asking whether the crisis of mainstream political parties in Western democracies also represents a deeper crisis with democracy itself. The first of three “risks in focus” considered in Part 2 of the Report assesses three related reasons to think so: the impacts of rapid economic and technological change; the deepening of social and cultural polarization; and the emergence of “post-truth” political debate. These challenges to the political process bring into focus policy questions such as how to make economic growth more inclusive and how to reconcile growing identity nationalism with diverse societies.

The second risk in focus also relates to the functioning of society and politics: it looks at how civil society organizations and individual activists are increasingly experiencing government crackdowns on civic space, ranging from restrictions on foreign funding to surveillance of digital activities and even physical violence. Although the stated aim of such measures is typically to protect against security threats, the effects have been felt by academic, philanthropic and humanitarian entities and have the potential to erode social, political and economic stability.

An issue underlying the rise of disaffection with the political and economic status quo is that social protection systems are at breaking point. The third risk in focus analyses how the underfunding of state systems is coinciding with the decline of employer-backed social protection schemes; this is happening while technological change means stable, long-term jobs are giving way to self-employment in the “gig economy”. The chapter suggests some of the innovations that will be needed to fill the gaps that are emerging in our social protection systems as individuals shoulder greater responsibility for costs associated with economic and social risks such as unemployment, exclusion, sickness, disability and old age.

Managing the Fourth Industrial Revolution

The final part of this Report explores the relationship between global risks and the emerging technologies of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR). We face a pressing governance challenge if we are to construct the rules, norms, standards, incentives, institutions and other mechanisms that are needed to shape the development and deployment of these technologies. How to govern fast-developing technologies is a complex question: regulating too heavily too quickly can hold back progress, but a lack of governance can exacerbate risks as well as creating unhelpful uncertainty for potential investors and innovators.

Currently, the governance of emerging technologies is patchy: some are regulated heavily, others hardly at all because they do not fit under the remit of any existing regulatory body. Respondents to the GRPS saw two emerging technologies as being most in need of better governance: biotechnologies – which tend to be highly regulated, but in a slow-moving way – and artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics, a space that remains only lightly governed. A chapter focusing on the risks associated with AI considers the potential risks associated with letting greater decision-making powers move from humans to AI programmes, as well as the debate about whether and how to prepare for the possible development of machines with greater general intelligence than humans.

The Report concludes by assessing the risks associated with how technology is reshaping physical infrastructure: greater interdependence among different infrastructure networks is increasing the scope for systemic failures – whether from cyber attacks, software glitches, natural disasters or other causes – to cascade across networks and affect society in unanticipated ways.

Note: Global risks may not be strictly comparable across years, as definitions and the set of global risks have evolved with new issues emerging on the 10-year horizon. For example, cyberattacks, income disparity and unemployment entered the set of global risks in 2012. Some global risks were reclassified: water crises and rising income disparity were re-categorized first as societal risks and then as a trend in the 2015 and 2016 Global Risks Reports, respectively. The 2006 edition of the Global Risks Report did not have a risks landscape.