Four ways the conflict in Ukraine will change the approach to risk management

Global risksArticleApril 28, 2022

The invasion of Ukraine has changed the risk landscape for generations to come. How businesses assess, plan and mitigate risks will also need to change. Here’s how…

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has caused tragic loss of life and destruction as well as unleashing a major humanitarian crisis with more than 5 million refugees fleeing the country and over 7 million internally displaced in Ukraine.

But the impact of the conflict goes far beyond the borders of Ukraine. The global scale of the political and economic disruptions has not been seen since World War II and there is still no end in sight to the conflict.

For businesses, it has created risks to their people, assets, operations, reputations and supply chains in the region and globally. Risks that for many seemed totally unthinkable in 2022. It meant many businesses were woefully unprepared. And it has caused business leaders to reassess their approach to risk management. Here are four ways that risk management should change:

1. Geopolitics must move up the risk agenda

Other than Brexit and concerns over a possible U.S.-China trade war, geopolitics has not been front and center on most risk radars that have been preoccupied by the COVID-19 pandemic and climate risks. But the conflict in Ukraine is a reminder that geopolitics can have deep ramifications – at least in the short to medium term.

“During the pandemic and subsequent lockdown restrictions, companies were able to find alternative operating models to enable them to continue business virtually and remotely. But the fallout of geopolitical events can act more like an unavoidable catastrophe event,” says Eugenie Molyneux, Chief Risk Officer for Commercial Insurance at Zurich Insurance Group.

The conflict in Ukraine is creating a global risks superstorm. It includes supply chain interruptions, resource scarcity, food shortages, trade credit risks due to the removal of some Russian banks from the SWIFT global payments platform, greater inflationary pressures and other risks associated with the unprecedented sanctions and countersanctions. It is also another reminder of the close link between geopolitics and energy security, which can have destabilizing impacts on the global economy.

In many cases, actions taken by businesses to reduce one risk can exacerbate others. “Many companies are openly supporting Ukraine and suspending trade and investments in Russia. But this can create risks for your employees located in Russia. It also raises the possibility of becoming a target of cyberattacks,” explains Molyneux.

“Having an intimate knowledge of these diverse, complex and developing geopolitical risks is critical to identify challenges before they become problems. And you need an understanding of these risks across your entire value chain. Even if your business is insulated from these risks, what about your customers? What about your suppliers, or your suppliers’ suppliers?”

2. Worst-case scenarios should to be reassessed

“We’ve been too optimistic in the West and that’s because we’ve lived in a fairly stable environment since World War II. It has caused us to become blinkered as to what worst-case scenario can actually look like,” says Molyneux.

“I have frequently been told that the risks I highlight are too bleak and too negative. But even my worst-case scenario regarding the conflict in Ukraine has been exceeded, particularly with the speed of escalation and extent of its global impact. It highlights the need for greater diversity in the risk assessment process and a need to adopt more pessimistic worst-case scenarios.”

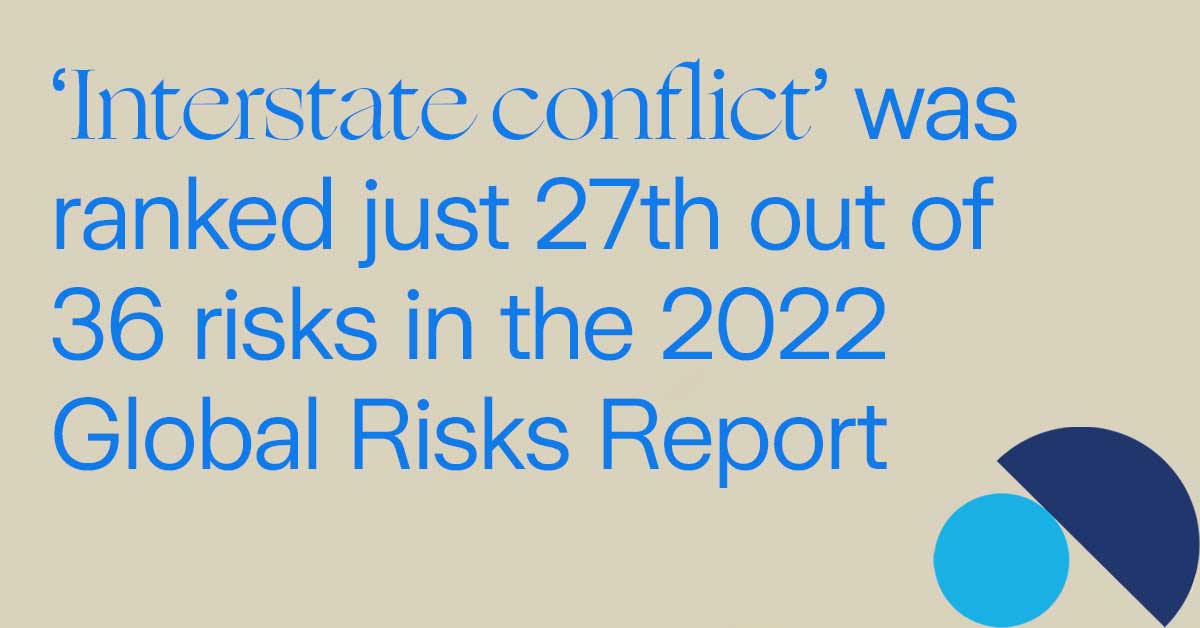

Molyneux’s views are supported by data in the World Economic Forum’s 2021 Executive Opinion Survey that forms part of the 2022 Global Risks Report where interstate conflict (“conflict between states with global consequences”) was ranked just 27th out of 36 risks.

But many Eastern European countries and former Soviet countries ranked interstate conflict in the top three. All the Baltic countries – Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania – ranked it number one and must be struggling not to say “I told you so” to their NATO and EU partners who should have listened to countries with a far deeper understanding of the Kremlin. Georgia (1st), Armenia (1st), Tajikistan (1st), Kyrgyzstan (2nd), Moldova (3rd), Bulgaria (3rd) and Poland (3rd) also ranked it in the top three. In Ukraine, interstate conflict was ranked the third highest risk, while tellingly in Russia, respondents ranked it first.

Molyneux says both countries and businesses can suffer from bias in their risk assessments that can cause them to neglect high impact risks, such as pandemics or geopolitical conflicts. She references global strategist and commentator Michele Wucker in the 2018 Global Risk Report.

“This behavioral element is crucial to managing risks effectively,” says Wucker. “Our brains play tricks that make some risks appear to be more or less likely than they are in reality.”

Wucker says leaders can offset these distortions by ensuring there are diverse voices around the table and by encouraging structured debate and constructive dissent. “Among other things, too little diversity can heighten confirmation bias and make it more difficult for individuals to speak out about risks for fear of disrupting consensus,” Wucker explains.

The conflict in Ukraine has dramatically changed the global risk landscape – worst-case scenarios need to keep pace.

3. Leaders need to avoid ‘availability bias’ and change mindsets

Zurich’s Molyneux says a reassessment of worst-case scenarios needs to apply to the threat of cyberattack, but many business leaders will find this challenging.

“Many leaders focus on what they can see and have seen. So in terms of cyberattacks they will mostly think of the NotPetya attack of June 2017. But this falls into the trap of Michele Wucker’s concept of ‘availability bias’ where decision-makers rely on examples and evidence that come immediately to mind.”

Wucker says availability bias “draws people’s attention to emotionally salient events ahead of objectively more likely and impactful events.”

As well as overcoming availability bias, Molyneux says leaders also have to adopt a new risk mindset. “In risk management, we develop and assess a lot of scenarios, we plan for these scenarios, and we develop mitigating actions. Everything is carefully planned.

“But the current situation is moving so fast that we have to undertake active risk management. It means taking decisions using imperfect information, which means leaders have to accept that they will get some decisions wrong. This is unchartered territory for many leaders. Most are hired to work in a usual paradigm. But we’re in an emergency paradigm that requires a different mindset.”

4. Outdated risk management techniques to make a comeback

“Old fashioned risk management techniques are very relevant to the world we are living in. Particularly in our supply chains,” says Molyneux.

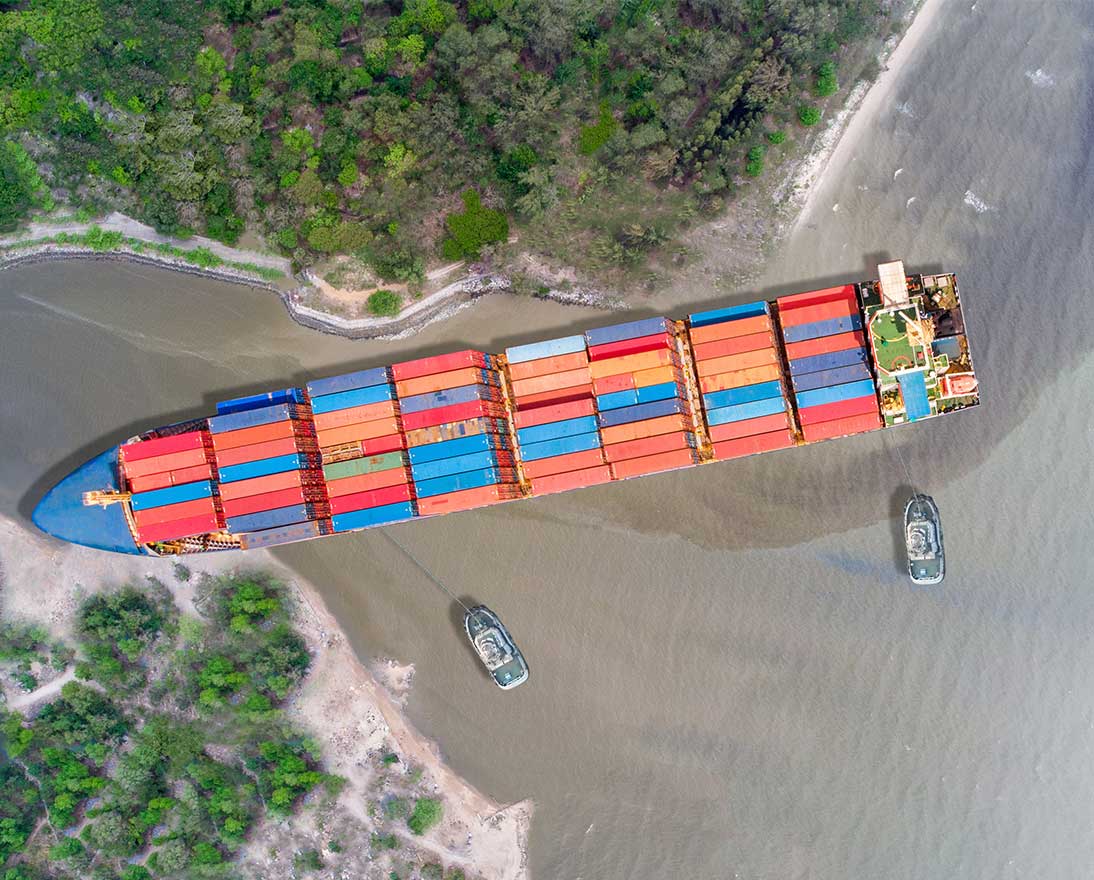

Just as global supply chain woes related to the pandemic were starting to soften, the conflict in Ukraine has delivered another shock. As well as the reliance in Europe on gas and oil from Russia, there is a global dependence on both Russia and Ukraine for key agricultural commodities, including wheat, corn, sunflower oil and fertilizer. Russia is also a key global source of critical minerals including palladium, titanium, nickel and neon.

Supply chain issues may also compounded by a shortage of Ukrainian and Russian seafarers, who make up 14.5 percent of the global shipping workforce with many holding senior rank with critical responsibilities.

COVID-19 and now the conflict in Ukraine has exposed the fragility of our global supply chains and the vulnerability of production strategies, lean inventories and just-in-time replenishment. To increase resilience, many businesses are trying to diversify supply chains and introduce dual sourcing. Others are investing in artificial intelligence that can create smart and nimble supply chains able to quickly shift production strategies.

But Molyneux suggests considering more old-fashioned techniques. “There now needs to be more emphasis on holding stocks, shorter and more localized supply chains, and even bringing manufacturing in-house.”

Molyneux says businesses also need to revisit system modularity. When systems within a global organization and its value chain are highly interdependent, a change in one can drastically affect the performance of the others. These effects can cascade and lead to the failure of the entire system.

“Having the same systems across an organization is desirable, in normal times. But it creates a difficulty right now as you cannot easily isolate part of the business. “If may feel like we’re going back to the future, but system modularity, if done correctly, can significantly improve resilience.”