Taking the measure of biodiversity

Climate changeArticleNovember 3, 2022

There is a growing awareness of the need to align voluntary carbon markets with efforts to promote nature and biodiversity as essential tools in the fight against climate change.

As the urgency of combating climate change becomes ever greater, a growing number of companies are turning to voluntary carbon markets to offset their carbon emissions – a vital step along the path to net zero.

This year, the market for voluntary carbon credits – as opposed to credits bought for compliance reasons – surpassed USD 2 billion for the first time, and it has quadrupled in size since 2020. Forest and land-use projects have shown the strongest growth – from 57.8 million credits traded in 2020 to 227.7 million last year.

Yet a growing body of research shows that not all carbon projects benefit nature and biodiversity, which are fundamentals pillars in mitigating climate change, building resilience into food systems and maintaining the quality of air and water.

John Scott, Head of Sustainability Risk at Zurich Insurance Company Ltd (Zurich), argues that carbon-offset projects can only become truly effective tools in helping to combat climate change if they also benefit nature and biodiversity.

“It’s time for businesses to realize that you cannot do business on a dead planet,” he says. “We have to make the connection between nature and carbon projects.”

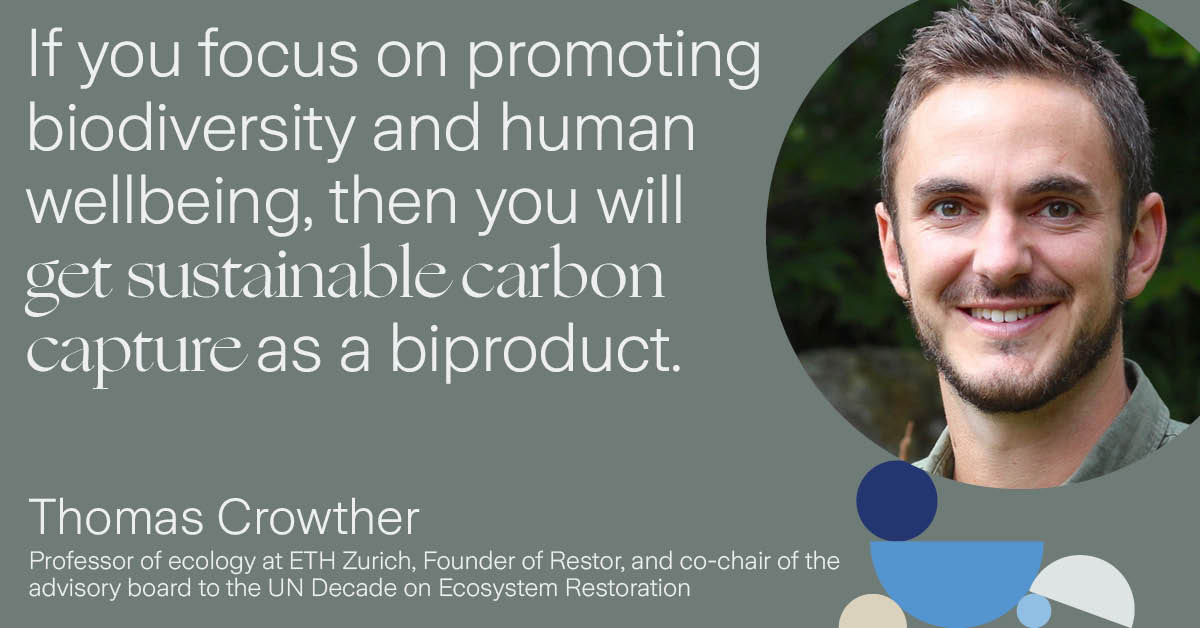

Thomas Crowther, a professor of ecology at ETH Zurich, Founder of Restor, and co-chair of the advisory board to the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration, says that carbon projects need to focus on nature and biodiversity rather than on sequestering carbon, per se.

“If you’re trying to capture carbon and, hopefully, helping biodiversity and people along the way, you’re likely to fail and cause more harm than good,” he says. “If you’re trying to restore healthy biodiversity for the wellbeing of local people, then you’re far more likely to get healthy carbon capture because carbon is the byproduct of healthy ecosystems.”

The importance of biodiversity in trying to limit climate change has risen steadily up the sustainability agenda, and December’s UN Biodiversity Conference has already published a draft of an accord that sets a base goal of ensuring that at least 30 per cent of land and sea areas are conserved through effectively managed well-connected systems of protected areas.

But what is the best way to measure biodiversity given the complexities of ecosystems? And how could it be used to inform companies’ and investors’ decisions as they look to use voluntary carbon markets to offset their emissions?

John Scott at Zurich argues that investors in carbon projects until now have often lacked a good understanding of the quality of the underlying assets and the underlying schemes. “A lot of money has gone into things that haven’t actually done what they said they would do,” he says.

In response, bodies such as The Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market, an independent governance body for the voluntary carbon market, are working to lay down a set of so-called core carbon principles, which help to identify and define what makes a good-quality carbon-removal project.

Another initiative, by the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD), a body representing financial institutions and corporates, is looking to develop a risk-management and disclosure framework for organizations to report and act on evolving nature-related risks.

In particular, TNFD is establishing metrics to help understand how the companies that investors are supporting are interacting with nature and biodiversity, not just by looking at a specific asset in a specific geography but by how that asset or activity impacts nature through its supply chain.

Meanwhile, Crowther and others are working towards creating a globally standardized simple measure of biodiversity for any given location on the planet as a way to make comparisons, assess the impact of a carbon footprint as well as to see how biodiversity complexity changes over time – whether in a positive or negative way.

“We work with a large network of academics around the world using a multi-dimensionality approach to collapse as many of the global layers of data as possible about the genetic composition of plants, microbes and animals at any location,” Crowther explains. “We can then come up with a measure for every 10m2 patch on the planet from 0 to 1, with zero being a square of asphalt to one being a natural, intact ecosystem.”

Together, the hope is that these initiatives will make carbon-offset projects and voluntary carbon markets focus more closely on nature and biodiversity as essential pieces in the sustainability puzzle.

In the meantime, however, Anja-Lea Fischer, Global Head Operational Sustainability at Zurich, says that companies and investors can take immediate steps to raise the importance of biodiversity in their sustainability strategies. One of the most important, she says, is to incorporate nature and biodiversity into their due-diligence.

“Ultimately, you are buying an invisible commodity so it’s incredibly important that you understand who you are working with,” she says. “Even if you are not yet active in the voluntary carbon-market space, there are opportunities to influence through your power as a business – whether that be your suppliers, your customers or in your investment decisions.”