Lifers (Part I) 1969–79: Manual typewriters, Bermuda shorts and cigarettes

PeopleArticleFebruary 17, 2023

What has it been like to work at Zurich for over 40 years? We asked our longest-serving employees around the world how they’ve seen the company culture evolve over the decades.

It was November of 1969, and Mike Berrenson was in limbo. He was 18, just out of high school in Baltimore, Maryland, and, like most American men at the time, eligible for the draft – with the Vietnam War still raging. When he failed his physical because of a bad arm, he enrolled in a local community college, but it left him uninspired.

Not only was the year coming to an end, but the decade and an era – the Sixties. Woodstock, and all that it represented, was in the rearview mirror, and anyway Mike had always been more pool hall than flower power, more in tune with his hometown of Charm City than Haight-Ashbury. He needed to do something with his life, but what?

Besides eight-ball, he was also good at math, so when he heard Maryland Casualty Company (which would eventually become part of Zurich) needed an audit reviewer, he applied. The interview process, as it were, consisted of 10 math questions. “That was the extent of it,” Berrenson says now. He got the job, and today, at 70, is the longest serving Zurich employee worldwide. “Who knows what would have happened had I been drafted?”

It may have been over 50 years ago, but he remembers his first day like it was yesterday: cigarettes, ashtrays and smoke everywhere; single file desks, no cubicles, most with no phones; and men were required to wear ties. He was given a huge, analog calculator from, like, the last century, and as he recalls, was told something along the lines of, “Hey, start adding these field audits, kid.”

“It weighed a ton, that thing,” Berrenson says. “You punched in the numbers as hard as you could, pulled the handle, the tape came out, and that was your answer.”

Then there was his first pay stub. “A hundred and seven bucks a week,” he says. “And no overtime back then.” Not a lot, but not bad for a teenager. “Every Friday, you were handed your paycheck, walked across the street to the bank, cashed it, and that was your money for the week,” he says.

Soon after, he dropped out of community college and just continued to show up for work. And show up and show up. “And all these years later,” he says, “it hasn’t stopped.”

Teen spirit in Portugal

Antonio Bico was a year younger than Mike Berrenson when he joined Metrópole in Portugal on March 2, 1970. There were no marches on the capital, no social revolution in Lisbon at the time – not yet anyway. The Carnation Revolution – the peaceful overthrow of the Estado Novo regime – would come in 1974, but there were armed conflicts in the former Portuguese colonies, Angola and Mozambique among them.

Young Antonio was still a few years from his compulsory military service, though, and could immerse himself in all matters of Metrópole, which was owned 95 percent by Zurich. The 17-year-old was introduced to a formal but welcoming group – with cigarettes, ashtrays and smoke everywhere. Men wore jackets and ties, women dresses and skirts. It was very hierarchical but there were also a lot of young people who played on the Metrópole sports teams – football, basketball, volleyball, you name it – that competed against other companies in Lisbon. That was a nice icebreaker.

If 17 seems young, consider that Manuel Duarte was hired as a paquete, a kind of bellhop, at Metrópole on July 21, 1970, a few days before his 14th birthday – and six days before the death of longtime dictator Antonio Salazar – which sounds like something out of a Wes Anderson film. “I still see myself walking through the door of the headquarters for the first time on Rua Barata Salgueiro, where it remains.” He has stayed with Zurich in a variety of roles, because, he says, “my job still gives me a lot of pleasure – I still feel motivated.”

Antonio, meanwhile, started in claims, where he wrote and received letters on mountains of paper. When he returned from his compulsory two-year military service in 1976 – fortunately he avoided war-time action – he continued to learn about every nook and cranny of the business. “I grew up in the company,” he says. Indeed, he grew all the way up to CEO of Portugal in 2007. He only recently stepped down as CEO, but is staying on to consult, because, he says, “I love what I do. It’s part of my life.”

Strict dress codes in Chicago

The Zurich office in Chicago was 4,000 miles from Lisbon, and 700 from Baltimore, but it had at least one thing in common in 1970: cigarettes, ashtrays and smoke. On June 25, 1970, another 17-year-old, Carol McArdle, commuted to the Zurich office in downtown Chicago – 111 W. Jackson Boulevard – for her first day as a claims draft typist. She was two weeks out of high school when she answered a job ad in the newspaper and was understandably nervous. She had never even gone into the city by herself.

“I didn’t want to go to college,” she says, “and back then you didn’t need a degree. I didn’t like typing – I hated typing in school – but I passed their test. They didn’t want speed, they wanted accuracy. But you couldn’t make a mistake, so it was very intimidating. And though the people were nice, they were all a lot older than me. I think the next youngest person was probably in their 40s.”

There were plenty of other women in the office, but they weren’t allowed to wear pants, just skirts and dresses. Men were in jackets and ties. Phones were only on supervisors’ desks. What was new were the typewriters. Gone were the big old manual typewriters. In were the big electric typewriters. “I never saw an electric typewriter before,” she says. “I didn’t even know how to turn it on.”

After three months, Carol found typing monotonous, so she went to her boss and asked if there was anything else. He said no. But that weekend she saw more job ads at Zurich for all kinds of positions, so, with the encouragement of her father, she went back to the boss and was like, hey what gives? He relented and she was transferred to the accounting department processing cancellation credits for three months. Then she moved into the rating and coding department, where there were more young women her age.

“That first year, I did this for three months, then moved over there for three months, and started learning new things. My dad said at the time, ‘Don’t give up.’ And it ended up all working out.”

A day job Down Under

Like Carol, Kathie Grierson was nervous, petrified, on her first day. It was September 1, 1975, and the 20-year old Australian, like so many at the time, loved Stevie Nicks and Christine McVie and had Fleetwood Mac playing in her head, especially ‘Rhiannon’ and ‘Landslide.’ She also loved the Eagles, ‘One of These Nights’ and ‘Lyin’ Eyes.’ It’s no wonder she was attuned to the pop sounds of the day; she had, after all, come to Melbourne from Perth in Western Australia three years earlier to take up a career in dance but thought it might be time to find a day job. She had gone to night school to be a secretary and, through the government employment service, applied to Guardian Royal Exchange (which would be acquired by Zurich).

She sat in on reception, helped in the mail room, ordered stationery and filled the copy machine with toner and paper. “I hated doing the toner,” she says. “It got all over me.” If she hated the toner, she loved her managers: Mr. Lush and Mr. Cohen. No first names were ever used, and if you didn’t know their last name, you called them Sir. “To this day,” Kathie says, “I still find it hard to call them by their first names when talking about them.”

Certain things were the same Down Under – smoking, of course – but miniskirts were allowed in the office, as were bellbottoms and platform shoes. This being Australia – and the 1970s – men would often come to work in safari suits or (heaven help us) Bermuda shorts with socks to their knees. Supervisors had their own room in the canteen and could also have beer and wine. On Fridays, everyone went to the pub for lunch.

“A lot of deals,” she says, “were signed on a drink coaster, or so I was told.” There was also a ‘tea lady’ that came around with tea and biscuits – savory in the morning, sweet in the afternoon. “Mary was her name – I can’t believe I remember.” And there was a ping-pong table – long before they became de rigueur at hip tech start-ups.

At the end of 1975, Kathie went back home to Perth for Christmas to see her family. They saw ‘Jaws,’ which had just opened in Australia – “between you and me, I had my feet up on the seat screaming when the shark came up to the boat” – and had a great holiday. They were happy she got that day job, one with a future. “Little did they know I would still be here nearly 47 years later.” Or, put another way, in the words of her beloved Fleetwood Mac: ‘Don’t stop....’ well, you know the rest.

From Zurich’s 150th Anniversary Book.

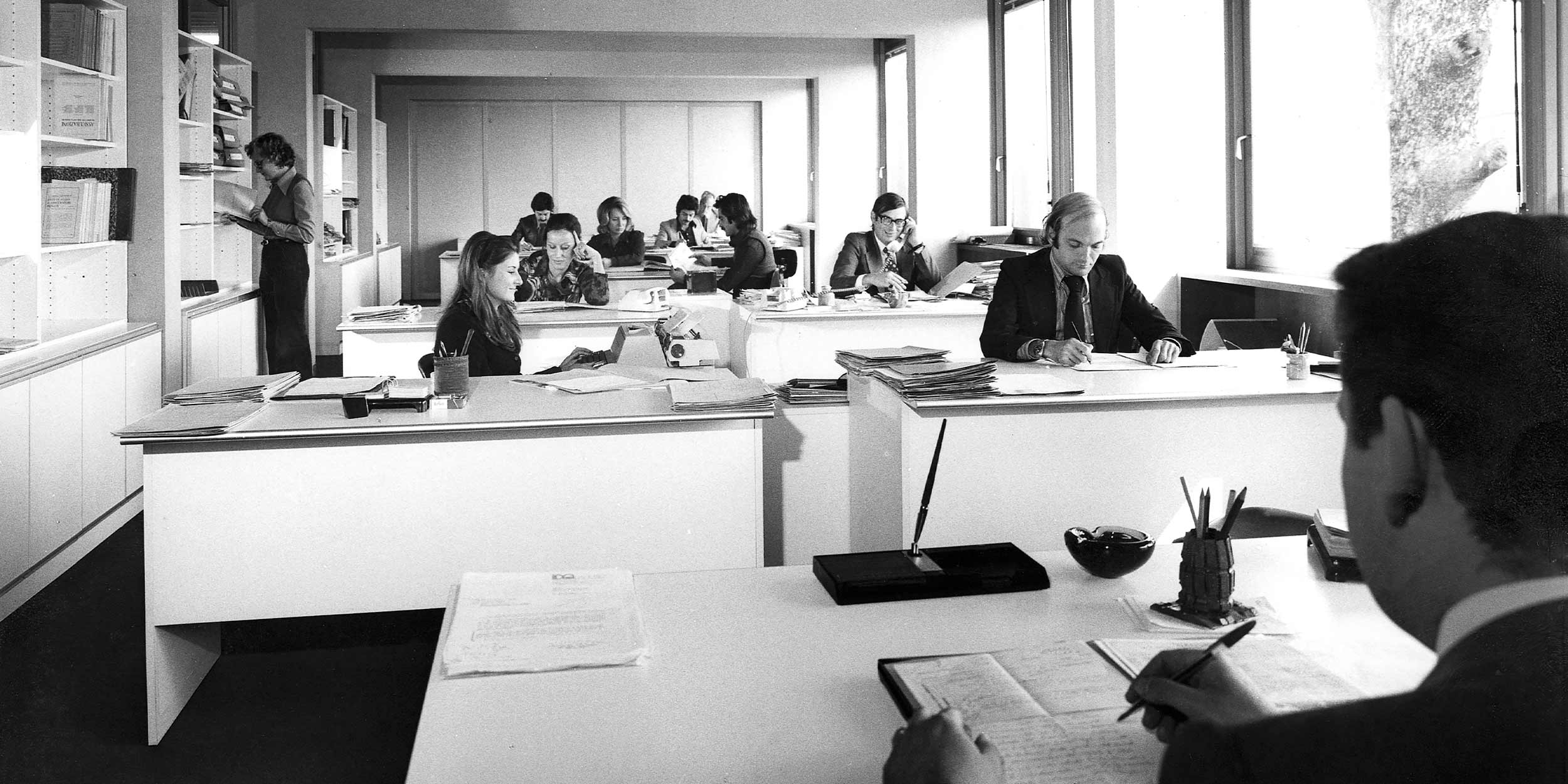

Photo: Claims office of the Zurich subsidiary Danubio in Italy (1974).