How the magic came to Madison Square Garden

PeopleArticleNovember 3, 20228 min read

From Muhammad Ali and ‘The Fight of the Century’ in 1971 to Harry Styles just recently – with Michael Jordan to Michael Jackson in between – the legends always bring their best when they perform at ‘The World’s Most Famous Arena.’ And Zurich had a hand in its creation over 50 years ago.

Buried deep in Zurich’s archive, among all sorts of unexpected surprises, is a small tray, about 10-by-20 centimeters, with an image of New York’s Madison Square Garden under construction in the mid-1960s. Above the image it reads “We helped make it happen” along with the Zurich logo to mark the 100th anniversary of Zurich North America in 2012. As they say in the Big Apple: “Who knew?”

In the early 1960s, Madison Square Garden, located on Eighth Avenue and 50th Street, was already in its third incarnation. The first two, from 1879–1925, were, true to the name, on or near Madison Square Park, at Fifth Avenue and 23rd Street.

When it was announced that the Garden would move yet again, this time on the site of Pennsylvania Station at 33rd Street and Seventh Avenue, it wasn’t exactly celebrated. After all, Penn Station, the grand Beaux-Arts treasure, was beloved by preservationists, architecture enthusiasts and the public alike. It was designed by McKim, Mead & White, one of the country’s foremost architecture firms (and, ironically, the designers of the second Madison Square Garden) and completed in 1910. Among its many virtues was the grand, light-strewn main waiting room, which was inspired by the Baths of Caracalla in Rome.

But the developers won out, and the massive engineering project lasted from 1963–68. First, Penn Station had to be taken down while relocating the entire station below ground and keeping it functioning – with its 250,000 daily passengers and 650 trains. At the same time, the vehicular and pedestrian traffic on the busy Seventh and Eighth avenues was expected to continue flowing. Then the new Garden and an office tower had to be erected on the site.

A Garden grows in the big city: Ten years ago, for its 100th Anniversary, Zurich North America paid tribute to the helping hand it gave in constructing the ‘new’ Madison Square Garden in 1968.

It was Zurich North America that provided liability insurance and workers’ compensation – financial reimbursement for injured employees – for the project. It also hatched an accident prevention program to offer protection to the 1,000 workers on the site. The “new Garden” was finished in early 1968, and the first show was a salute to the U.S.O., the nonprofit military charity, hosted by Bob Hope and Bing Crosby and broadcast on national TV by NBC, whose employees were also insured by Zurich North America.

If that debut event was ho-hum, especially to a younger generation – Hope and Crosby were past their prime by then – the nation’s eyes would be back on the new Garden in the spring of 1970. That was the year the long-suffering New York Knickerbockers – one of MSG’s two permanent residents along with the (also long-suffering) New York Rangers of the National Hockey League – won their first NBA Championship. They were led by their inspirational captain Willis Reed (who famously limped onto the Garden hardwood just moments before the start of the seventh and deciding game) and the league’s most stylish player Walt “Clyde” Frazier, who got his nickname from wearing a similar hat as Warren Beatty in Bonnie and Clyde and whom Puma would soon name a sneaker after – long before Nike’s Air Jordans. (Speaking of Michael Jordan, he has said that MSG was his favorite place to play. And no wonder: In his first game there as a pro in 1984, he put up 33 points, eight rebounds and five assists and had the basketball connoisseurs of New York oohing and aahing. Even in his last game there in 2003, as a 40-year-old with the Washington Wizards, he poured in 39 points.)

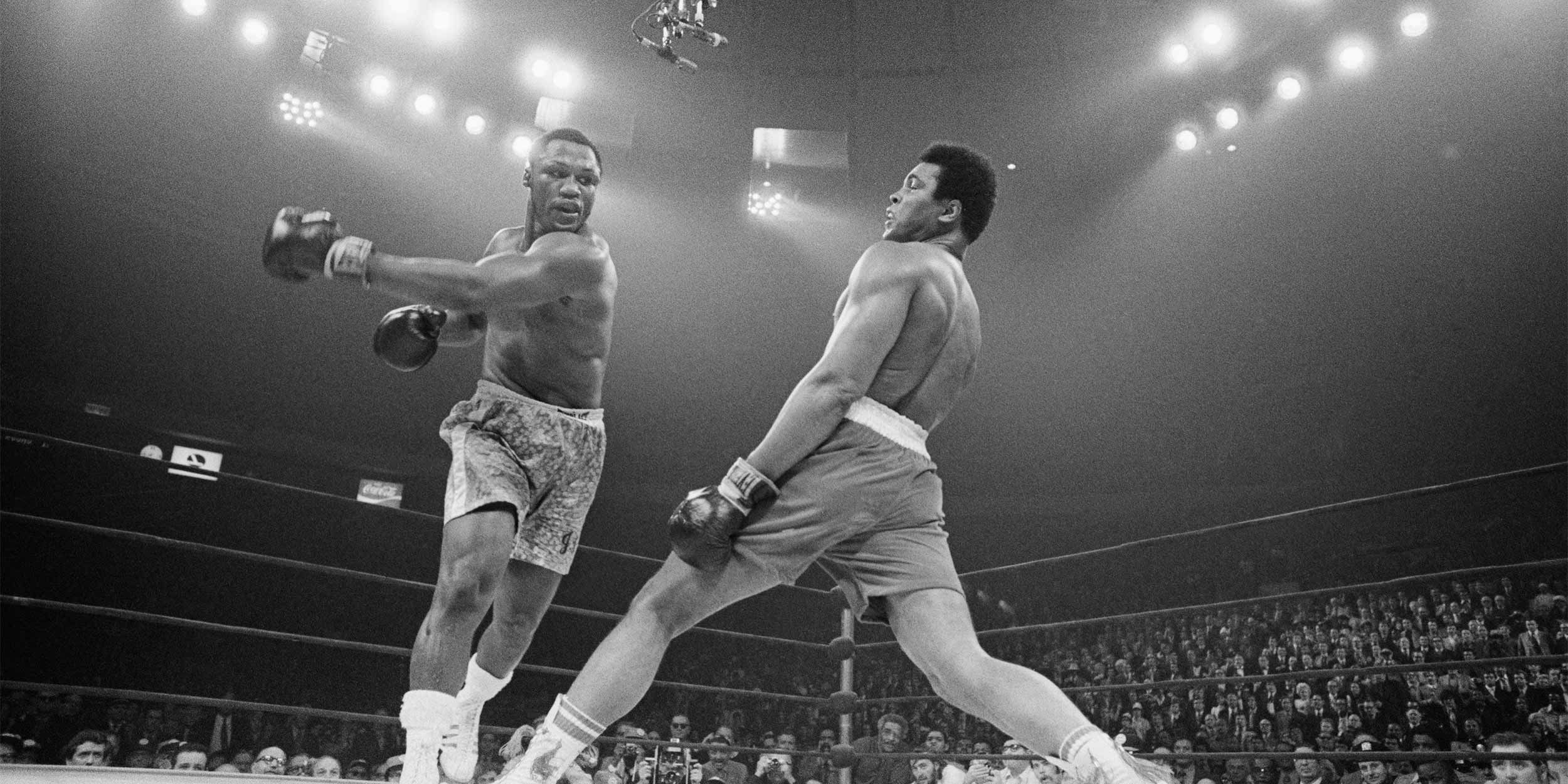

But the event of the era would come in 1971 when Muhammad Ali – recently back after his three-and-a-half-year ban for refusing to serve in the U.S. Armed Forces and by extension the Vietnam War – took on Joe Frazier in an attempt to regain his heavyweight title (see photo above). Both fighters were undefeated, and it was billed as “The Fight of the Century” or, simply, “The Fight.” It was such an impossible ticket that the only way Frank Sinatra could get in was to take photographs at ringside for Life magazine. (And his photos were pretty good, too.) Burt Lancaster was one of the announcers. In the 15th and final round, Smokin’ Joe landed his signature left hook and sent Ali to the canvas. It was a miracle Ali even got to his feet, but Frazier would win the decision, while Ali suffered his first loss. After the fight, celebrated gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson wrote that the fight was “a proper end to the Sixties.” In other words, it was more than a fight. And it placed Madison Square Garden at the center of the universe. Hence its slogan: “The World’s Most Famous Arena.” The Ali-Frazier rematch also took place at MSG, and Ali would have two more fights there, winning each time.

Now, would another insurer have stepped in if Zurich North America hadn’t in the early 1960s? Possibly, maybe, to quote Björk (who played MSG in 2007). But then again, given the massive undertaking and risk, maybe not. And if the old Garden fell into disrepair as it was likely to, would the Knicks and Rangers even have stayed in New York City? Would “The Fight of the Century” have landed there? There was no guarantee. Remember, in 1957 the beloved Brooklyn Dodgers left Ebbets Field for Los Angeles, and the New York Giants abandoned the rickety Polo Grounds in Harlem for San Francisco. In 1976, The New York Giants of the NFL left the city for a brand-new stadium across the river in New Jersey.

The new Garden also coincided with the rise of arena rock. Would Led Zeppelin have played at the old, smaller Garden in 1973? Maybe, maybe not. But their three-night stand at the new and improved Garden became the basis for the classic documentary The Song Remains the Same.

The new Garden attracted George Harrison’s Concert for Bangladesh in 1971 and Elvis in ’72. It showcased Frank Sinatra in ’74, singing this time – though in a boxing ring, perhaps inspired by Ali-Frazier – and the Rolling Stones ad infinitum; The Who to Stevie Wonder; Bob Marley to Madonna to Michael; The Godfather of Soul, James Brown, to the Queen of Soul, Aretha Franklin; James Taylor to Taylor Swift; Biggie to Beyoncé; and just last month Harry Styles’s sold-out 15-night residency, which saw his name raised to the rafters, previously reserved only for longtime New York legends like Patrick Ewing and Mark Messier (and, sadly, Billy Joel and Phish).

There were also two popes (John Paul II in 1979 and Francis in 2015), Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus and the political circuses of both the Democratic and Republican conventions.

It’s hard to believe, but MSG is now the oldest arena in the NBA and NHL, and there are calls to build yet another new one. When it was first completed in 1968, not everyone was happy, though more with Penn Station being taken down. The most scathing words came from Yale art historian Vincent Scully, who wrote: “One entered the city like a god. One scuttles in now like a rat.” But the vitriol slowly mellowed over the years and to so many now it’s an endearing landmark in the cityscape.

Back to that tray tucked away in the Zurich archive: “We helped make it happen.” It’s true, but maybe it’s more apt, and powerful, to put it in sporting lingo: Zurich North America provided an assist, a vital one, in the re-making of Madison Square Garden – and, as every sports fan knows, assists lead to goals, some of them unforgettable.

Photo credits (from top): Ali-Frazier, Getty Images; Zurich Insurance Group Ltd.’s archive (2); MSG (aerial), Anthony Rosset/Unsplash; MSG (street level), Willian Justen de Vasconcellos/Unsplash.