5 great skeptics who dared to think differently and were proven right

SustainabilityArticleJanuary 13, 20236 min read

We salute original thinkers and skeptics who boldly challenged conventional thinking about our planet to radically improve our understanding of global warming and climate science.

One half of the 2021 Nobel Prize in Physics was jointly awarded to climatologist Syukuro Manabe and climate modeler Klaus Hasselmann for their groundbreaking research into the causes of climate change.

But what makes this a remarkable story is not for why they were honored; it’s for when. Because much of Manabe and Hasselmann’s most significant pioneering research work was conducted in the 1960s and 1970s, decades before climate change became widely accepted.

This is often the role that great and groundbreaking thinkers have to play: sailing into unchartered seas, thinking radical thoughts and remaining defiantly skeptical that humanity’s current understanding of how the universe works is entirely correct.

At Zurich Insurance Group (Zurich), we understand the value of questioning long-held assumptions and looking beyond the horizon to identify future risks.

As John Scott, Zurich’s Head of Sustainability Risk, says: “Thinking creatively, being curious and exploring the limits of our current understanding of the world help us to identify and prepare for problems before they happen. It’s a way of thinking that’s helped both scientists and insurers improve not only our understanding, but also our resilience to risk. This is one of the reasons Zurich sponsors and supports the annual Global Risks Report, which has an impressive track record in highlighting emerging threats to global stability ahead of time, including the climate change crisis.”

In this article we look at how early climate scientists laid the foundations on which modern climate science was built. They challenged conventional wisdom but were ultimately proven right in the end. Sadly, as many climate protestors’ banners proclaim, “every disaster movie starts with someone ignoring a scientist.”

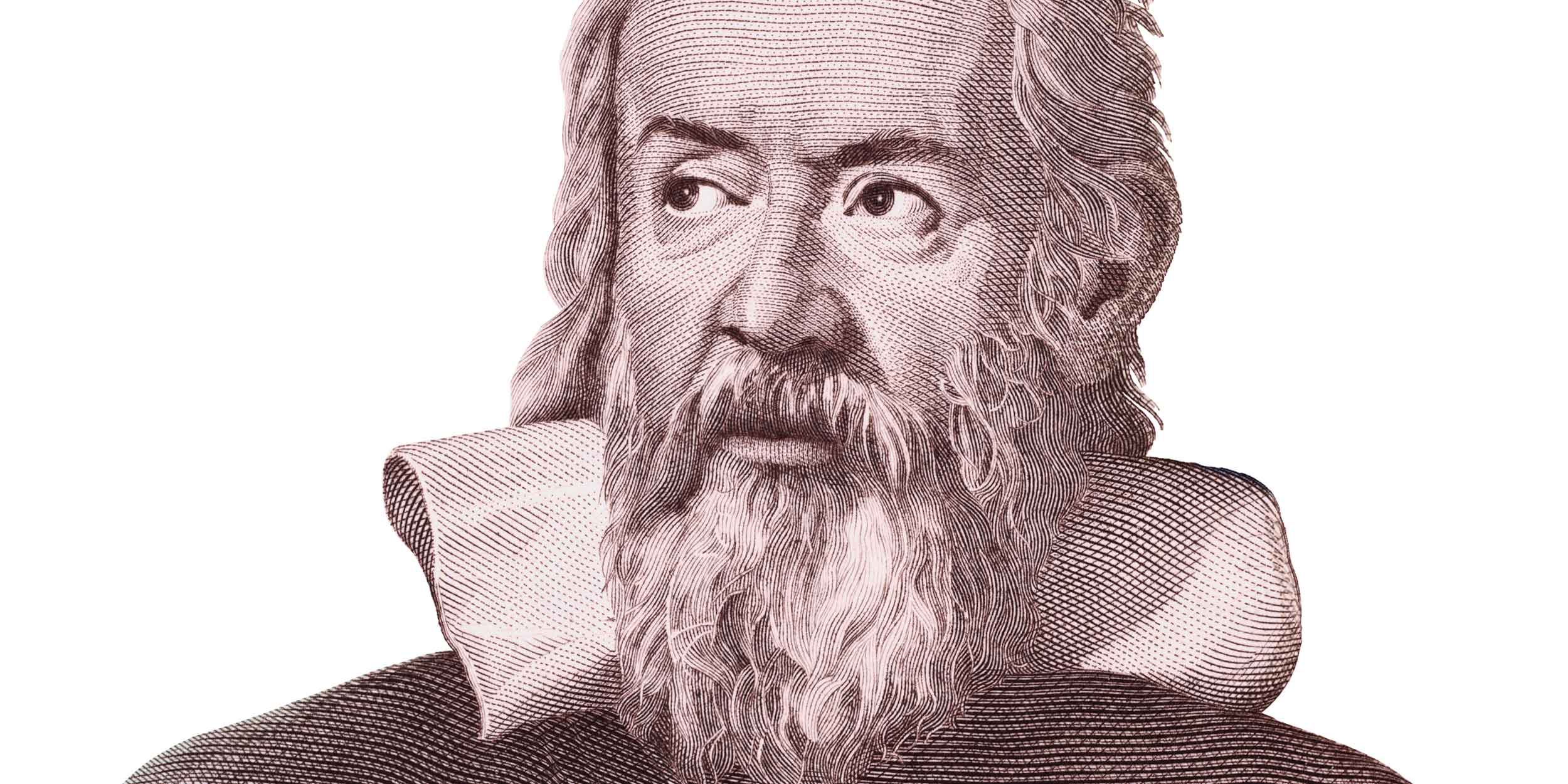

But we start with one of the most famous skeptical thinkers, Galileo Galilei. He may not have been a climate scientist, but he did challenge beliefs about our planet and is considered a pioneer of evidence-based scientific methods that modern scientists have followed.

Galileo Galilei — astronomer arrested for his observations

In 1633, the great Italian physicist and astronomer Galileo was arrested and interrogated by the Catholic Church for refusing to accept the Christian scriptural view that the Earth was the immovable center of the universe. Galileo’s own astronomical observations of the heavens had convinced him that the “heliocentric” theory put forward by Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus, which proposed that the Earth and other planets revolved around the Sun, was in fact correct.

Despite the wealth of evidence supporting Galileo’s position, the Church condemned his views and banned his books. Galileo was prevented from teaching his “heretical” views again and spent the rest of his life under house arrest. Three hundred and fifty-nine years later, the Catholic Church finally conceded that Galileo had been right all along and officially cleared his name.

Svante Arrhenius – first linked CO2 to global warming

In developing a theory to explain the ice ages in 1896, Swedish physical chemist Svante Arrhenius was the first to use basic principles of physical chemistry to calculate the extent to which increases in atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) will raise Earth’s surface temperature through the greenhouse effect.

These calculations led him to conclude that human-caused CO2 emissions from the vast quantities of coal burned to power the Industrial Revolution’s steam engine-powered locomotives, ships and industrial factories was enough to cause global warming. A conclusion which has been extensively tested, winning a place at the core of modern climate science.

Charles Keeling – laid the foundation of modern climate change research

American professor of oceanography Charles Keeling’s first major contribution was his development of the first tool to measure CO2 in atmospheric samples in the 1950s. Then, after joining the staff at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego, he designed and built a CO2 monitoring station on the Mauna Loa volcano in Hawaii in 1957 and another in Antarctica. These remote locations ensured they were far away from local sources of CO2 to allow reliable detection of changes in the background atmosphere.

Keeling showed that CO2 levels were rising steadily in what came to be known as the “Keeling Curve,” which he attributed to the use of fossil fuels. He also observed a seasonal pattern with CO2 levels highest in the spring, when decomposing plant matter releases CO2, and are lowest in the fall when plants stop taking in CO2 for photosynthesis.

Many may have moved on to other scientific investigations, but Keeling understood the power of long-term observations and, despite many funding crises, relentlessly pursued the measurements. Thanks to Keeling, we have highly accurate records of atmospheric CO2 spanning over 60 years, which has risen from 315ppm in 1958 to 416ppm in 2021. Keeling’s work has helped reveal the existence of the greenhouse effect and global warming.

Syukuro Manabe – made breakthroughs in climate modeling

In the late 1960s, Syukuro Manabe was working at Princeton University in the U.S., where he was the senior meteorologist at the Program in Atmospheric and Oceanic Studies. It was here that he applied the mathematical calculating power of early computers to the problem of modeling climate. In fact, Manabe’s climate circulation model ran on a computer that only had half a megabyte of memory despite being big enough to fill a room.

After running hundreds of hours of tests, Manabe’s model demonstrated how increased levels of CO2 in the atmosphere lead to increased temperatures at the surface of the Earth. “He was the first scientist to do a thorough calculation that was reliable,” said the secretary of the Nobel physics committee, Gunnar Ingelman, in a statement. Today, almost every climate model relies on Manabe’s work.

Klaus Hasselmann — showed climate models were still reliable despite changeable weather patterns

Klaus Hasselmann’s research, conducted in his role as a professor at the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology in Hamburg in Germany, had a similar impact. In 1980, Hasselmann was able to explain why climate models could still provide reliable predictions despite weather patterns being inherently chaotic and changeable. He also pioneered new methods of measuring the impact human activity has on global temperatures.

In this way, Manabe and Hasselmann joined the great tradition of scientists and thinkers who have dared to think differently – and eventually persuaded the rest of us to see the world in the same way.