Have we entered the decade of global risks?

Global risksArticleJanuary 4, 20236 min read

Are we living in an era in which world events trigger unavoidable cascades of crises?

Crises have always rippled out into the world around them, creating far-off and sometimes unanticipated effects. However, the early years of the 2020s have demonstrated the interconnectedness of global risks with a fresh force.

Few decades have had a less auspicious beginning. In 2020, COVID-19 swept across the globe, spreading to over half of the world’s countries in just three months and causing knock-on economic, political and social shocks. At the same time, the frequency and the cost of natural disasters have continued to increase: in 2020 alone, 389 major climate change affected almost 100 million people and caused USD 171 billion in damages. The pandemic was beginning to abate when Russia’s invasion of Ukraine triggered food and energy crises which fueled a rise in inflation and left us on the brink of a global recession.

Are we now living in the decade of global risks, in which world events trigger an unavoidable cascade of crises? And how can businesses and risk managers look to mitigate these risks? We expect this to be a key focus of the World Economic Forum’s upcoming Global Risk Report 2023, an analysis of the most pressing threats facing the world developed in collaboration with Zurich Insurance Group.

The COVID-19 pandemic

From huge gaps in vaccine availability to fraying social cohesion and a global supply chain crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic triggered a multitude of risks that reverberated around the world. What followed were two long years of immense pressure on global healthcare systems, severely limited public freedoms and a paradigm shift in the way that the global economy operated. These trends are a focus of the last Global Risks Report, which examined the cascading impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and the ongoing complications it has introduced to global efforts to coordinate on issues such as climate action.

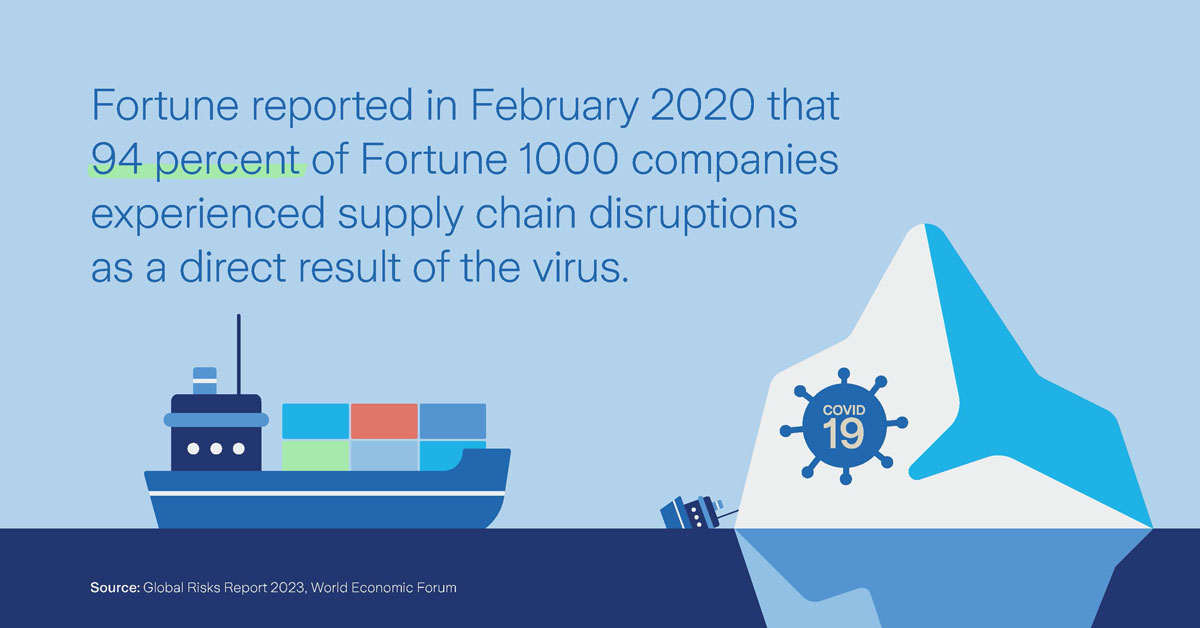

While first and foremost a human tragedy, the pandemic also caused ructions in the global economy. Fortune reported in February 2020 that 94 percent of Fortune 1000 companies experienced supply chain disruptions as a direct result of the virus. The shock and uncertainty fed into a period of considerable market volatility in which the Dow Jones Industrial Average lost 37 percent of its value between February and March 2020 before rebounding dramatically in June 2020. But it was the economic rebound - as lockdown restrictions were loosened following the successful development and rollout of vaccines - which contributed to tight supply chains and the resurgence of inflationary pressures in 2021 and commodity price increases.

The initial political responses to COVID-19 were focused on protecting national interests, with significant spread of misinformation, politically-charged accusations of responsibility for the virus and hoarding of PPE, in contradiction of multilateral health agencies’ best advice. Panicked governments largely ignored health professionals and, in some cases, removed the leadership of national Centres for Disease Control (CDC) and stopped funding of the WHO.

Past Global Risks Reports have frequently discussed the risk of pandemics to health and livelihoods. The 2020 edition (compiled and published before the COVID-19 pandemic began in earnest) identified the fact that many health systems across the world were stretched. The 2018 and 2019 editions shone a spotlight on the threat of antimicrobial resistance. And the 2016 edition stated that the Ebola crisis would “not be the last serious epidemic” and that “public health outbreaks are likely to become ever more complex and challenging”.

The lessons delivered by the COVID-19 pandemic and the changes to the geopolitical and economic risk landscape that it generated arguably laid the foundations for the next set of risks to be triggered, when geopolitical tensions led to the first interstate war in Europe for 70 years with dramatic economic and societal consequences.

The Ukraine conflict

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has further destabilized the geopolitical order. The aggression triggered the greatest refugee crisis in Europe since World War II, internally displacing eight million people and causing a further six million to flee to neighboring European nations.

The COVID-19 pandemic issued some hard lessons about the interdependence of global risks, but few could have predicted the extent of the instability that would follow. Another dramatic shift in global economic, societal, environmental and technological risks was triggered in February 2022, driven this time by a new war in Europe.

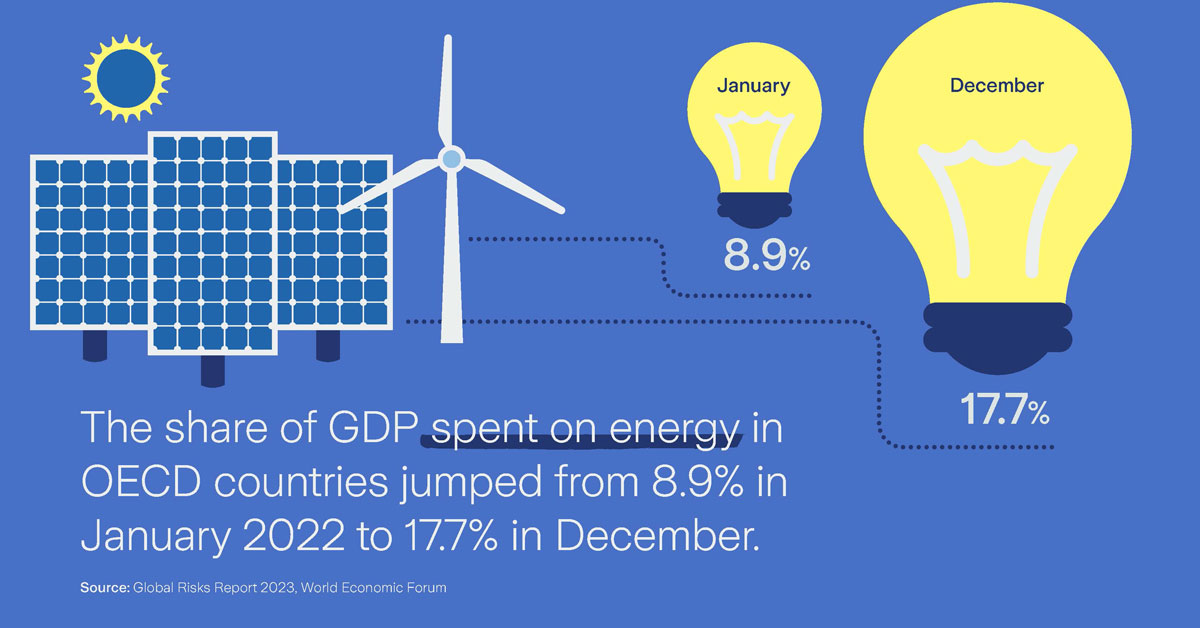

The global energy market was already reeling from shortages and price rises as a result of the pandemic. The invasion exacerbated this and created the greatest energy price shock since the 1970s: the share of GDP spent on energy in OECD countries jumped from 8.9 percent in January 2022 to 17.7 percent in December.

Food prices also spiked as a result of the conflict. Between them, Russia and Ukraine account for almost 30 percent of global wheat exports and play a key role in the supply of fertilizer. The blockade of sea ports and the destruction of croplands exacerbated a pre-existing global food crisis in which 345 million people in 82 countries are facing acute food insecurity. In richer countries, inflation is eroding living standards and making it harder for central banks to fight the risk of recession.

Carbon emissions climbed as the post-pandemic economy fired up and tightening supply chains drove rising prices. Food and energy have been weaponized by the war in Ukraine, contributing to soaring levels of inflation and a globalized cost of living crisis that is fueling social unrest. The remedial shifts in fiscal and monetary policy mark the end of an economic era defined by easy access to cheap debt, generating significant implications for governments, companies and individuals as well as widening inequality within and between countries.

The consequences of the interdependencies between geopolitical tensions and socioeconomic risks, have driven world leaders’ collective focus to be on ‘survival’ of today’s “emergency” - the crises that are driven by the risks of cost of living, social and political polarization, food and energy supplies, and geopolitical confrontation. Yet much-needed attention and resources are being diverted from longer term risks and trends including climate change, natural ecosystems, human health, security, digital rights, resource constraints and economic stability - that could become the polycrises which define the next decade.

Building resilience

These two case studies demonstrate the way in which crises are deeply interconnected. The cascading nature of global risks has created a far greater need for risk management practices to factor in this interdependency – when we plan for one risk, we must plan for all of its possible dependencies.

It is vital, as we continue to live through the decade of global risks, that businesses are proactive in their anticipation, identification, monitoring, and mitigation of risks and in the building of resilience to future shocks.