Mountain guides: insuring climbing’s brave pioneers

RiskArticleJune 13, 2023

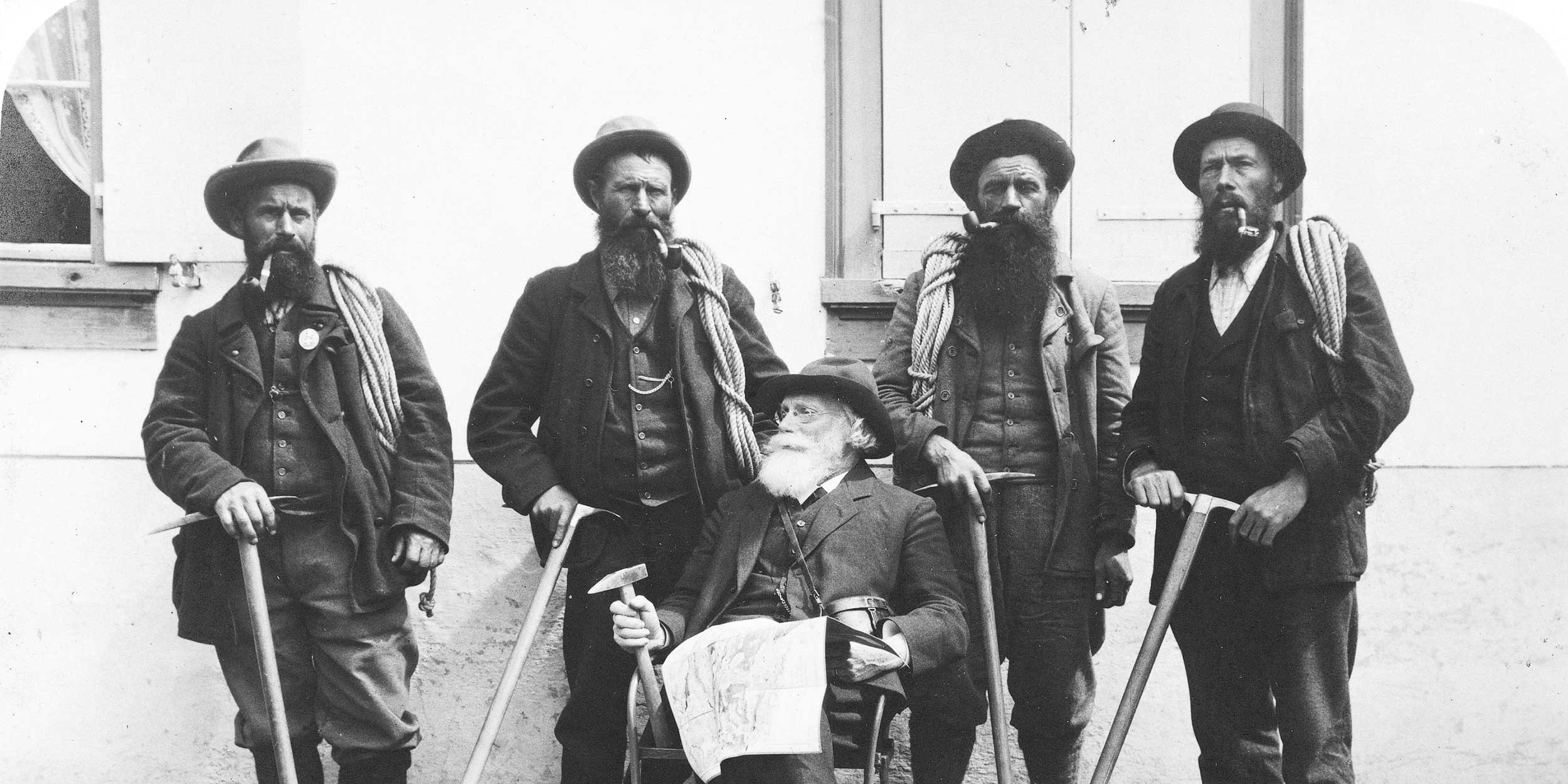

Climbing guides once scaled daunting summits with only rudimentary equipment and raw courage. Today the mountains – and their guides – still command respect.

On June 24, 1886, people living in Kals, in a valley leading to Austria’s highest peak, Grossglockner, were expecting an important visitor. Alfred Pallavicini, the dashing marquis, known to contemporaries as the strongest man in Vienna, was preparing for a new, daring alpine ascent. He had already caused a sensation 10 years earlier, reaching the Grossglockner summit via a risky new route up an icy couloir. At that time, crampons were in their infancy, and it was too dangerous to change positions on the way up. So, guide Hans Tribusser led the whole way, hacking 2,500 steps in the ice. By the standards of the day, it was extreme mountaineering. The route is still called the Pallavicini ‘Rinne’ to honor that first dangerous ascent.

In light of such exploits, Zurich’s decision to become the first Swiss insurer covering mountain guides for accidents back when the sport was still new might have seemed like a risky decision. The idea gained momentum, however, thanks to Swiss pastor Gottfried Strasser. Preaching to his flock in the village of Grindelwald next to the imposing Eiger, he took the lead in urging the Swiss Alpine Club (SAC) to introduce insurance for guides to support them through injuries, and their families in case of death.

Strasser was persistent, and persuasive. A poet, he had a way with words. And it took a lot of convincing to introduce guides to insurance, and insurance to guides. At the outset, some doubters even suggested that insurance would create a moral hazard, leading guides to risky adventures, secure in the knowledge their families would be provided for! But, thanks to Zurich’s participation, Strasser’s vision was transformed from merely “a pious wish” into practical reality. Zurich introduced mountain guide accident insurance starting in Switzerland in the summer of 1881 and extended it to Austria and Germany in 1883.

A knife-ridge and the devil’s horn

In Kals, in that wet late spring of 1886, Pallavicini had engaged two local guides for his latest adventure. Together with Dutch diplomat Hermann Crommelin, he planned to traverse directly along a geography with imposing features like the Gröger Knife-Edge, the Glockner Wand (Glockner Wall) and Teufelshorn (Devil’s Horn) to reach the Grossglockner summit. Both the local guides – Christian Ranggetiner, and Engelbert Rubisoier – were very familiar with the terrain. Knowing the Glockner range as well as they did, they likely had misgivings about Pallavicini’s undertaking. Surrounding peaks were white with new snow, and fog drifted in and out. Hardly good climbing conditions. Nevertheless, Pallavicini, used to success, wasn’t to be dissuaded. So, the four climbers set out for the Stüdl hut on Grossglockner’s southwestern flank. And then – they disappeared.

When Zurich’s accident policy was introduced, to get cover, a guide had to be not only able, and licensed, but also “honest and have polite manners.” At the outset, there were numerous debates about what was covered by insurance. For example, whether freezing constituted a climbing risk. It was decided that if a guide froze in the line of duty after plunging into a crevasse, he was covered. But if the guide stopped for the night and froze during a bivouac, he wasn’t eligible to file a claim.

During the worrying days in Kals after Pallavicini’s party failed to return, a woman in charge of the nearby Stüdl hut went to open it. Not finding the keys, she forced the lock on the door. Inside she found the rucksacks, blankets and food belonging to the four climbers, evidently left behind. She saw none of the men. However, bad weather closed in, delaying any search. When at last other local guides could set out to look for the missing climbers, they found a sorry sight. The bodies of three lay broken at the base of high cliffs. The search continued until the searchers at last located the fourth missing climber, Pallavicini. He’d somehow survived the fall and, missing a shoe and an eye, lived long enough to crawl a fair distance until he’d expired by the edge of a ravine. Vienna’s strongest man had finally met his match.

Providing cover to those in need

Newspapers in Austria, Switzerland, Germany and England published moving accounts of the sensational tragedy. And one description also turned up in an unlikely place – Zurich’s in-house insurance periodical, ‘Die Unfall-Versicherung.’ In its journal, Zurich noted that it had insured both of Pallavicini’s guides. Christian Ranggetiner’s and Engelbert Rubisoier’s survivors duly received financial compensation.

The news of the accident drew other insurers’ attention to what they hoped might be a lucrative new market. Climbing, despite the risks, was becoming a trendy sport for Europe’s wealthy set. But, as Zurich might be forgiven for noting to its satisfaction, the competitors were “too late.” Zurich had firmly established itself as the market leader in insuring mountain guides.

The business of insuring mountain, glacier and similar guides against accidents seems to have had its share of claims in climbing’s early days. These included sprains, fractures, crush wounds, contusions, dislocated shoulders, bruised and broken ribs and skulls. And there were also unusual cases, including a claim filed by one game warden and mountain guide. He’d been shot. Around that same time, a newspaper account relating an accident to this guide related with glee a case of “divine justice.” When this same game warden (who evidently took pleasure in filling his fellow compatriots with buckshot, just for poaching a little meat, according to the paper), accidently shot himself, it might have seemed almost to be heavenly retribution, or so the newspaper assured its readers.

An era ends

When the SAC marked its 75-year anniversary in 1938, it observed in a jubilee publication that since mountain guide insurance cover began, it had led to a “loss” to the providers, which by that time had increased to four Swiss insurers. The SAC even went so far as to praise these insurers for their sacrifice.

While Zurich’s businesses no longer offer the type of accident insurance to guides common in the 19th and early 20th centuries, in Switzerland Zurich still supplies guides with professional liability insurance. Zurich also insures some of the SAC's huts, which today are in a few cases far more than huts. A few even boast warm showers!

According to Michael Wicky, the head of Bergpunkt, a Swiss-based professional mountain guide business that connects guides with potential customers, it can be difficult in modern times for mountain guides. But mountaineers tend to be highly resourceful, resilient men and women. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Wicky and others kept busy offering online climbing coaching.

Mountain guiding is not typically a profession in which to grow wealthy. But it offers other rewards to those who are passionate about it. “I am always looking to bring something special to those I guide,” says Wicky. He especially enjoys taking people into unfamiliar and remote places, “where they must overcome obstacles as a group.” Wicky adds with pride: “When the day is over, and the people who have mastered a climb can look back on their achievements with satisfaction, that, for me, is the biggest reward.”

A special thanks to Zurich’s archives for their support and insights in researching much of the historic information for this article.