Autism in the workplace: a rich talent pool awaits discovery

PeopleArticleMarch 27, 202311 min read

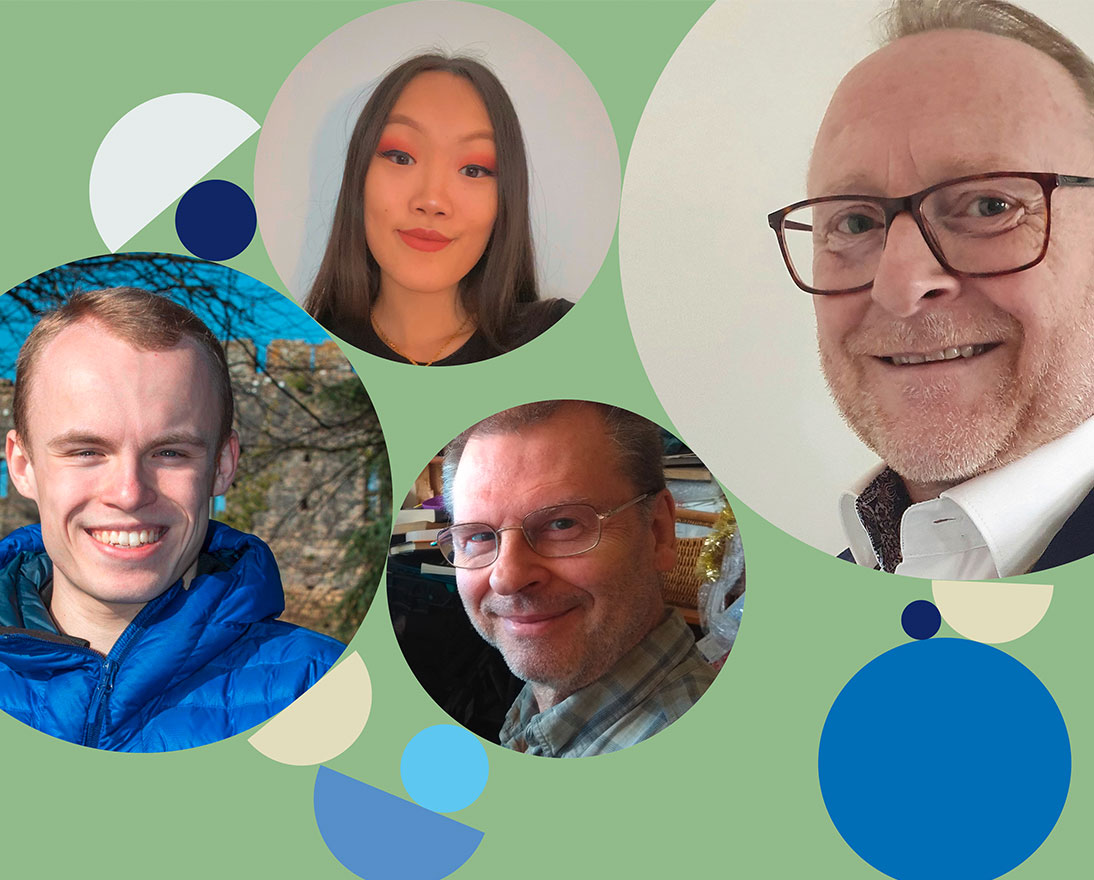

Autistic adults are wonderfully gifted people yet only 1-in-5 are in employment. Why is this talent pool being overlooked? With the help of insights and experiences from autistic Zurich Insurance Group employees we explore this question.

As a father of an 9-year-old autistic son, one of the most saddening statistics is that only 22 percent of autistic adults are in any form of employment – the lowest figure across all disability groups. And of those able to find a job, most are underemployed working part-time or in roles that do not utilize their many skills and talents.

It is not just an upsetting statistic but bewildering too as autistic people have so much to offer the workplace. This often includes a remarkable attention to detail that supports a high level of accuracy, excellent concentration levels and a narrow focus meaning they are not satisfied until a task is completed.

“I’m dedicated and stubborn. For me, it is very simple: if I’m given a task I do it. No matter the blood, sweat and tears I do it. I don’t give up,” says Lars Backstrom, an autistic consultant with auticon who has been working with Zurich Insurance Group for more than two years.

Luke Gawthorn, who has autism and will be rejoining Zurich UK as a graduate, says he’s able to be very focused and likes to analyze problems “microscopically.” He explains: “I dig into the inner details and focus in on a problem, which can often help find a solution.”

Autistic brains are also strong at recognizing trends and patterns and often excel at visual tasks. Take Charissa Khoo, a trainee actuary in Zurich UK who is autistic, has ADHD and a love of jigsaw puzzles. “People watch me complete a 1,000-piece puzzle – without looking at the box – and they’ll ask, ‘how on earth did you do that?’ And I’ll tell them, ‘I don’t know, I just see it’.”

Then there are personal qualities closely associated with autism, such as honesty, loyalty and dedication, as well as technical competency, superior creativity, reliability and excellent memory.

“I have insane recall, and it’s very helpful as I work with many complicated systems and processes,” says Jen Mayer, an autistic senior underwriting support manager in Zurich North America. “My memory capacity allows me to keep up with so many things. Operations has endless ins and outs, decision trees, compliance, departments to work with, constant fires that come up, and endless amounts of metrics to memorize. But once I see a thing, I know it. And I can replicate it the exact same way, every single time.”

In short, autistic people think and solve problems differently, and this neurodiversity brings a unique perspective to the workplace. As serial entrepreneur and Virgin boss Sir Richard Branson says: “The world needs a neurodiverse workforce to help try and solve some of the big problems of our time.”

What is autism?

Autistic brains think, communicate and process information differently to non-autistic brains. Autistic people often have different sensory experiences, too. This means they see, hear, feel and experience the world differently to other people.

Autism is a spectrum condition. All autistic people share certain challenges. But being autistic will affect them in different ways.

So why is this wonderfully rich talent pool being overlooked?

Simon Baron-Cohen, professor of developmental psychopathology and director of the Autism Research Centre at Cambridge University, believes he has the answer: “Autistic people have been overlooked too often because employers can’t see past social skills. That is a big mistake.”

Autism and social communication skills

The social skills that Baron-Cohen refers to are a major challenge for most autistic adults. Many find it hard to understand and respond to other people’s behaviors and may not have the skills to make friends or even engage in conversation. Some are painfully aware of their social deficits and end up avoiding interactions even if they desperately want to connect with others.

Lars says he has always struggled in social settings and describes himself as “functionally emotionally illiterate.”

“There is a common misconception that people on the autism spectrum lack empathy. For me, and many others, the opposite is true. We lack a filter and get easily overwhelmed by all the emotions around us,” says Lars. “I feel emotions, I see emotions and I can read emotions in others. But knowing how to act on these emotions is a mystery to me.”

This social awkwardness is exacerbated for many autistic people by an auditory processing disorder that means it takes the brain longer to process sounds, including conversation. In addition, it is common to suffer from sensory issues with over- or under-sensitivity to sights, sounds, smells, tastes, touch and body awareness. Put this altogether and social interaction becomes an incredibly exhausting experience, as Charissa describes here.

“When most people have a conversation, they focus on what is being said. But for me, especially in group settings, it can get overwhelming. I’m quite slow at processing words, especially if it’s a technical or unfamiliar topic of conversation. Then there’s the sensory aspect to worry about, where I can get agitated if it’s too bright or too noisy. I’ll then start to get stressed over how I’m presenting myself, like my body language and eye contact. Do I look engaged? Am I fidgeting? Have I been staring at someone for too long?

“All of this makes it difficult for me to understand what’s actually going on. And so, I can get really anxious because I’m wondering, ‘what if they talk to me because I’m now very confused?’”

Autism and work

These challenges make it hard to find employment, especially as the first step – the interview – requires strong social and communication skills.

“Interviewing is just a rebadged social skills test,” says Ian Smith, an operations manager in Zurich UK who is autistic and has ADHD. “Do you like the person sat opposite you, can you work with them, and will they get on with the team? It’s recruiting based on personality fits and recruiting in our own image. And it shouldn’t be about that. It should be, are they capable of doing the job and do I trust that they are going to do that job better than any other candidate?”

The recruitment process can be made more autistic friendly: from the job description and application form through to the interview. A few minor adjustments can ensure a company hires amazing autistic talent, rather than just selecting the person who interviews best.

But even if a new job is secured, the challenges continue. The commute to work can be difficult due to sensory issues. A journey by train, subway or bus – or simply crossing a busy road – can be incredibly stressful experiences.

Then there’s the office environment to contend. Background noises, smells from the kitchen area, office lighting that’s too bright or too dim, or unexpected interruptions at your desk. All of these situations – and many others too – can make the office a distracting and non-productive environment for autistic employees or even a stressful experience that can ultimately lead to meltdowns.

Reasonable adjustments

In the UK, employers have a duty to undertake “reasonable adjustments” – called “reasonable accommodations” in the U.S. – to ensure employees with disabilities are not substantially disadvantaged when doing their jobs.

Charissa suggests companies implement a reasonable adjustments policy for their neurodiverse employees. “For instance, noise canceling headphones can make a big difference for those with sensory difficulties, which would be especially beneficial in a busy office. I bought a pair over lockdown and they changed my life.”

Other examples may include providing autistic employees with fixed workstations in hot desking environments, or a quiet space where they can retreat if the open plan office becomes overwhelming. But ultimately, autism affects everyone very differently so reasonable adjustments need to be made on a case-by-case basis – there’s no fixed template.

Charissa believes the concept should be extended to ensure neurodiverse differences are not considered as performance issues or skill deficits. “If you benchmark people on communication skills, then an autistic person is going to struggle to meet that expectation,” she says. “It’s like judging someone with dyslexia on how long it took them to write a 50-page report – that would be unfair.”

The role of people managers

Clearly, people managers have a big role to play. Autistic adults appreciate consistency, controlled and structured environments, and – just like any team that works well together – clear communication. For instance, it helps if managers set clear objectives and avoid ambiguity, unnecessary detail or small talk when explaining new assignments. Complex and detailed instructions should also be given clearly and in writing rather than verbally.

In his thesis for his MSc at Cranfield University, Ian researched the topic and found that when there was good understanding and support from their managers, autistic employees excelled and outperformed other employees. But the opposite was true when there was a breakdown in communication. Autistic employees then found themselves on performance improvement plans, their work-life balance deteriorated, and they got depressed.

But it needs to be a two-way street, adds Ian, where employer and autistic employee listen to one another’s needs to find a way they can best work together.

“This is why I’m trying to be open about my condition and limitations with my manager. As a result, there has been a marked improvement in our communication because my manager is on the journey with me,” explains Ian.

Any changes that help more autistic people thrive in the workplace – from the recruitment process to management styles and reasonable adjustments – should also be open to all employees, adds Alice Jenner, an autistic employee at Zurich UK who works in the Salesforce and data team.

“A lot of the difficulties faced by autistic people are the same that neurotypical people face, they are just more intense,” says Alice. “So any adjustments or other changes to help autistic employees should be offered to all employees. This will help undiagnosed and other neurodivergent employees – or just neurotypical employees who may temporarily or permanently struggle with specific tasks or situations. It will also help to ‘normalize’ adjustments in the workplace so that autistic employees – who often feel excluded – don’t feel set apart from everyone else.”

Creating an autism-friendly culture

There is one other hurdle and that is office culture, which can reflect broader society. Sadly for Lars, he has endured traumatic job experiences due to the way he has been treated by other employees.

“Bullying is unfortunately a fact of life for many autistic people. Our social isolation and our social awkwardness mean we tend to get isolated at work. This makes it easy for us to be frozen out and become targets or scapegoats. This has happened to me. It has left mental scars and caused me to suffer from PTSD.”

In jobs where Lars has excelled, he has had colleagues and mentors that were supportive, tolerant and kind.

Be kind

We should all follow the words of my 6-year-old daughter (who adores her autistic big brother) and “be kind to the autistic mind.” But not everyone who is autistic has a diagnosis. Both Jen and Ian did not know they were autistic until their late 40s, Lars was 50. There is also a long list of other neurodiverse conditions – like ADHD, dyspraxia, dyslexia or learning disabilities – that mean many people experience, interact with, and interpret the world in unique ways.

So let’s not just be kind to the autistic mind, but embrace and celebrate all people who are different to us. Because wouldn’t the world be dull and lack color if we all thought exactly the same?

The parents’ perspective

Jen Mayer has a deep understanding of autism as her two sons, Lou (18) and Max (15), are also autistic and she admits that she worries about their employment prospects.

“I think a lot about it and what they could do. Lou would be a great coder or could work in accounting or actuarial because he’s insane with numbers. But he could never work in an office because his sensory issues mean he doesn’t like wearing clothes.

“Max barely speaks. I don’t know what he’s going to do, but he’s freaking brilliant so there’s got to be something that can utilize that brain. A company could really benefit from having his creativity and his questioning thought process behind it. But what could he do where he doesn’t have to speak to people?”