Understanding risk interconnectivity

Global risksArticleJanuary 7, 2015

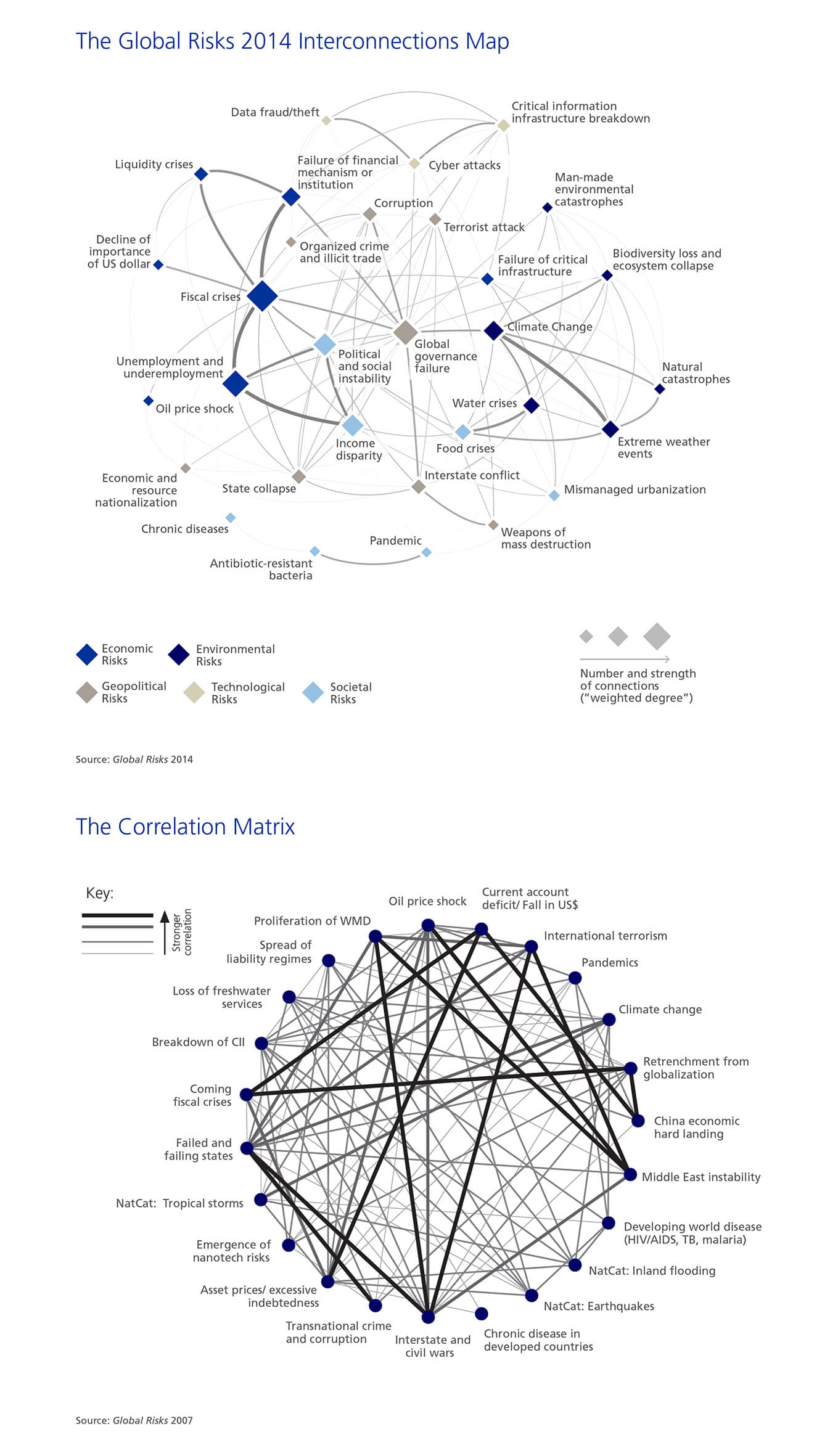

World Economic Forum's Global Risk report illustrates how links among risks can amplify the impacts, sometimes indirectly or unexpectedly.

The World Economic Forum’s Global Risks report—whose latest edition, Global Risks 2015, will be released on January 15—doesn’t just put its finger on the pulse of the top concerns of the year, helping people see risks that aren’t usually on their dashboards because the effects are indirect. It also points out how these risks are interconnected in ways that can amplify the impacts.

With hindsight some of these connections may seem obvious. However, it was Global Risks 2006 that first drew attention to how risks interconnect—and which also pointed out that effective mitigation requires a profound understanding of the interconnections ahead of time.

Since 2008, Zurich Insurance Group has partnered with the World Economic Forum as one of the main contributor of the annual Global Risks report. Over the years, the Global Risks report continues to bring together policy-makers, business leaders and non-governmental organizations to help align assessments of risk, to understand institutional gaps and to better grasp the interconnectedness of sectors and risks. Global risks in particular can be difficult for companies to visualize, and companies can't prevent such threats as natural catastrophes or chronic fiscal crises. Yet the commercial consequences are real. Identifying links between risks is crucial for understanding the big picture, the first step toward mitigating the effects of uncontrollable risks.

The ripple effect of risks is demonstrated in the fallout of the collapse of asset prices and fiscal crises since the global economic crisis of 2008. As those challenges have been worked on, the most significant risk facing the global economy has come to be seen as unemployment and underemployment, with severe income disparity featuring as the most likely global risk each year since the 2012 report. Youth unemployment rose in most regions since 2009, and over 25% of the world’s youth have no productive work. Discontent with economic conditions led to major protests in 11 countries in 2013. These risks are related to challenges for companies. Unemployment and underemployment can manifest in skills gaps for workers. Financial crises can tighten access to trade credit, choking business.

The risks perceived to be the most interconnected are macroeconomic. However, economic risks also are interconnected with other categories, such as societal risks.

For example, chronic disease in developed countries is linked to chronic fiscal imbalances. Prevention and treatment of diabetes alone was estimated to cost nearly $400 billion globally in 2010. Public spending on health-care in the European Union, for example, accounts for about 15% of all government expenditure, or about 8% of EU gross domestic product. Chronic disease also can tie back to unemployment, as corporations are hobbled by social charges or high health-care costs for employees.

Because chronic diseases tend to develop over years, they disproportionately affect the elderly, bringing up a link to mismanagement of population aging. People live longer, but suffer because they are not controlling their chronic ailments—and the elderly are more likely to have multiple chronic conditions. That creates a lost opportunity for elders to contribute to socioeconomic development.

Chronic diseases also are linked with severe income disparity. People with chronic conditions may be unable to work. In countries with limited or no government health programs, individuals may have a hard time paying for the cost of treating their chronic diseases.

Climate change presents another web of interconnected risks, linked to water supply crises, loss of biodiversity, rising greenhouse-gas emissions and also extreme volatility in energy and agricultural prices.

Constraints in water, energy or agricultural product supplies are connected to economic risks such as severe income disparity and more specific risks to the healthy functioning of the economy, such as supply chains. These risks are also linked to geopolitical risks, such as a backlash against globalization and global governance failure.

Critical systems failure was the top risk in terms of likelihood in 2007. It was among the top five in terms of impact in 2014 and, along with cyber attacks, in the top five most likely risks, illustrating the importance of digital technology to the global economy. While information infrastructure has proved to be resilient, the fear is that vulnerabilities could trigger a cascading failure of networks in an interconnected world.

A global governance failure is at the heart of many more risks, from chronic fiscal imbalances to unsustainable population growth, greenhouse-gas emissions, and critical systems failure. Global governance is essential for the international collaboration needed to make headway on so many global risks.

As the first Global Risks 2006 report pointed out, the impacts of interconnected risks can be greater than the sum of their parts. The increasing complexity of our world can lead “to rapid and unexpected contagion of global risks across industries and geographical areas.”

Global Risks 2015 will lay out a deep and distinctive analysis of risks and their interrelationships, which can help mitigate some of those risks and preserve resilience in our continually evolving world.