Rising social instability, a growing risk for global businesses

Global risksArticleMarch 29, 2015

Businesses need to consider a number of themes that may lead to social instability in their risk assessment of doing business in a country.

Social instability in the form of strikes, demonstrations and other types of civil unrest can have far-reaching and often unpredictable consequences for business and society as a whole. The effect on firms’ performance can be profound. The good news is that there are ways to assess and mitigate these risks that can leave companies in a better position to survive.

The World Economic Forum’s Global Risks 2015 report cited social instability, polarization and income inequality as major trends. Social instability is closely connected to other risks that rank high in the Global Risks report, such as unemployment, failure of national governance and fiscal crises.

“Companies need to understand the risks they are exposed to in their local markets, both directly and indirectly, and how these risks can mushroom into much bigger threats,” says Daniel M. Radulovic, Proposition Manager at Zurich Insurance Group. “Having access to timely information, having tools to monitor risks over time and the ability to model future scenarios over time should be part of every company’s enterprise risk-management tool kit.”

The Arab Spring is an example of how risks are interconnected and can create a domino effect, he adds.

The Arab Spring began when an unemployed 24-year-old Tunisian set himself on fire to protest his treatment by police. Spreading protests led to the fall of the Tunisian government and sparked similar action in a number of other Arab countries. Four long-lived regimes that had been considered stable were removed, while in Syria the protests escalated into a civil war that has claimed more than 200,000 lives and fueled the rise of the Islamic State movement.

Identifying risks and trends

“The Arab Spring caught many off guard, but the region was ripe for this kind of instability,” Mr. Radulovic explains.

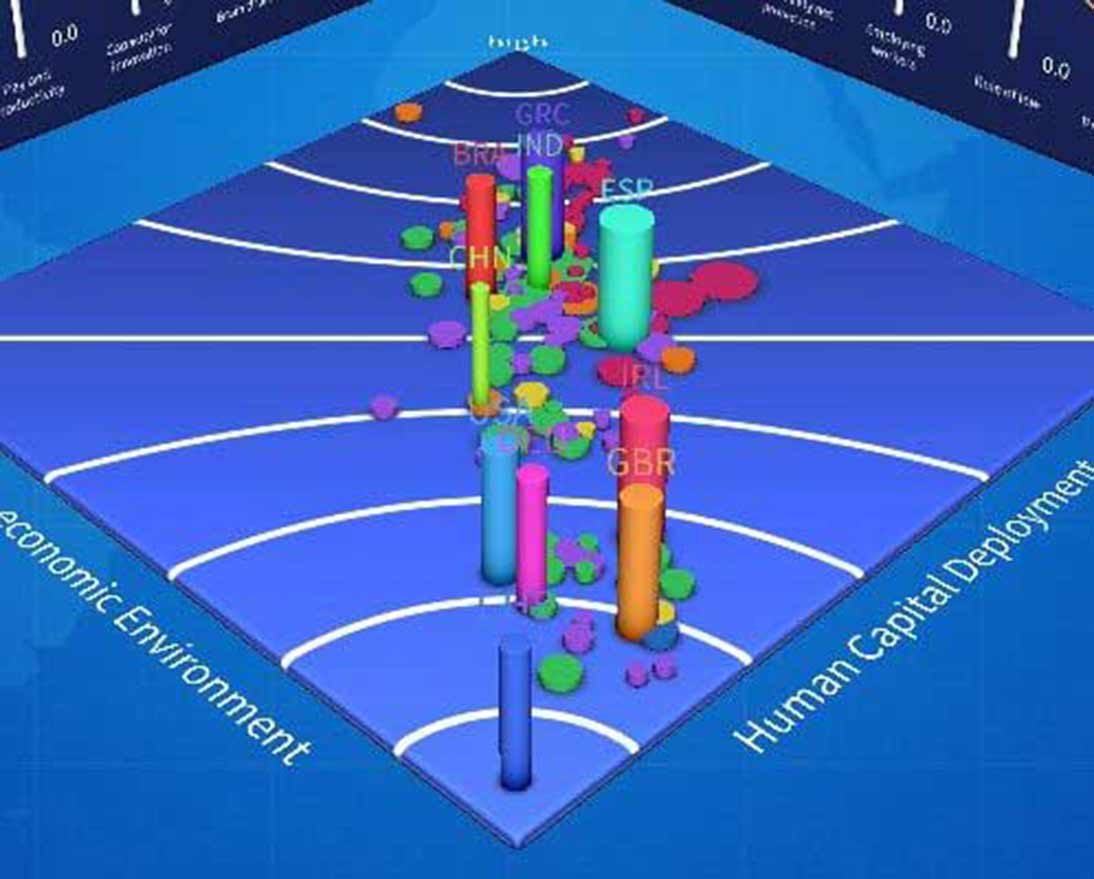

An analysis of the Arab Spring using the Zurich Risk Room, a tool that maps the connections between more than 80 risks in 174 countries, identified a broad mix of contributing factors behind the widespread and contagious protests. These included economic disparity, high youth unemployment, brain drain, rising food prices, lack of access to loans, political volatility, crime, corruption, poor social safety net protection, expropriation and human-rights abuses.

“If we apply that analysis to other countries around the world, we can see countries that have similar types of risks and that raises some red flags for potential social instability,” says Mr. Radulovic, who runs Zurich’s Risk Room. “It isn’t a crystal ball. It can’t possibly tell us that in six months a country will have protests. But it can say that a country is similar and needs to be monitored, because if certain risks get even worse, conditions might reach a tipping point and go from being unstable to protest to armed conflict or regime change.”

Such scenarios can help companies assess the risks in the countries where they operate, as well as the extent of their exposure.

“The challenge facing enterprise risk-managers is how to take the information that’s out there, how to interpret it and how to put into place mitigation strategies that can help companies avoid some of these risks,” Mr. Radulovic says. “To do that you have to make sure you’re aware of all the risks the company faces, monitor those risks on a regular basis and try to quantify the impact of those risks.”

Economic disparity links to other risks

One of the main ingredients of social instability is economic disparity. “It’s always a combination of risks, never one or two in silos,” Mr. Radulovic says. “Economic disparity coupled with political volatility is the combination of risks that makes a country ripe for social instability.”

“The reality of poverty varies considerably between countries, as does people’s outlook,” says Ortwin Renn, Professor of Environmental Sociology and Technology Assessment at the University of Stuttgart in Germany and co-author of a paper for the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development on social unrest. “In Burma, people are poor but mostly equal, and it seems that they hope things are getting better.”

Food prices jumped from 2006 to 2008, but the global forecast was for boom times. After falling in 2009, food prices climbed again, and economic crisis gripped most of the world. Amid a bleak future with high unemployment, the second rise in food prices was the final spur and made an individual Tunisian’s protest grow into the Arab Spring.

Economic disparity is closely related to unemployment and underemployment. Global unemployment stood at 5.9%, compared with 5.5% in 2007, before the global economic crisis, according to the International Labor Organization. Youth unemployment is nearly three times higher than for older workers, even though the younger generation has attained higher levels of education.

Social unrest surged in 2009, after declining—along with unemployment—in the 1990s and 2000s, the ILO says. Social unrest is now 10% higher than before the crisis.

Free markets, rule of law

Unemployment isn’t a sufficient condition for unrest. Unemployment rates during the economic crisis topped 25% in both Greece and Spain, and neared 15% in Ireland. But while Greece has seen many protests, some violent, Ireland and Spain have had fewer, even though Greece was one of the less unequal countries in the OECD, says Takis Pappas, Associate Professor of Comparative Politics at the University of Macedonia in Thessaloniki, Greece, and author of the recent book “Populism and Crisis Politics in Greece.”

However, with a higher number indicating greater perception of corruption, Greece stands out for weak governance, ranking No. 71 on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index as the crisis took hold in 2009, versus No. 32 for Spain and No. 14 for Ireland.

“What causes corruption? Is it income inequality?” Prof. Pappas asks. “No. It has to do with rule of law, whether the constitution in a country is respected, whether there are strong institutions of horizontal accountability, independent courts, etc.”

The simple political reaction to economic stagnation is populism, Prof. Pappas says. “The more populism gains strength, the less secure the environment for business and investment,” he says. “If I were a corporation, I’d try to invest in places where rule of law is strong and where feelings are not against open markets, but the reality is that many of the emerging markets, where the growth is, are weak in those areas.”

Some solutions to volatility

While companies have little power to reduce social instability, they can be good citizens, pay fair wages and start programs to make neighborhoods better, which “have very often helped address the unhappiness due to loss of social equity,” Prof. Renn says. Often, successful foreign investment begins with a community officer being assigned to work interactively with local communities as the project or operation develops.

Companies also can work with governments to identify the skills and jobs needed, Mr. Radulovic says, so that funds for training and education are put to the best possible use.

Corporations also need to focus on risk mitigation. They may want to transfer some of their risk via insurance, such as political risk policies that offer coverage for losses due to political violence, expropriation, currency inconvertibility or government default.

Companies are also increasingly looking at the role their captive insurance can play in managing these risks. The credit losses coming out of the global financial crisis, and in the past few years the political risk insurance claims, have not only made risk managers more aware of the risk, but also of the value that insurance can bring. There are ways to protect the supply chain as well—through supply-chain insurance, backup production or diversifying the supply chain into more stable countries, says David Anderson, Senior Vice President at Zurich Credit & Political Risk.

“Social volatility has a number of components, and each country is different,” he says. “There isn’t any one-size-fits-all indicator for social instability and political volatility. That’s what makes it such a challenge. But there are measures firms can take to get ahead of the risk and be resilient when these types of events unfold."

Disclaimer: Views expressed on this page and in the reports are not necessarily those of the Zurich Insurance Group, which accepts no responsibility for them