Global Risks Interconnections Map 2016

Global risksArticleJanuary 13, 2016

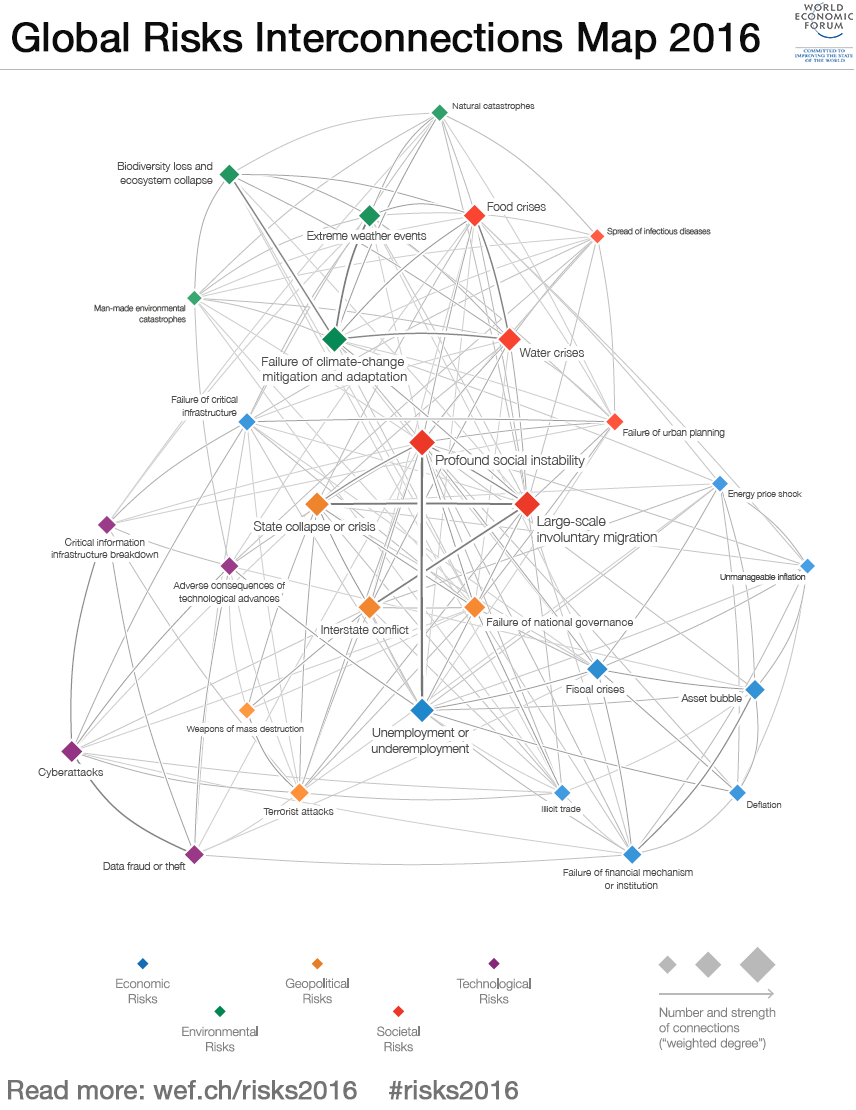

What are the risks to business of highest concern in the long- and short-term? See how the risks are interconnected as shown in The Global Risks Report which continues to raise awareness about global risks and their potential interconnections, and to provide a platform for discussion and action to mitigate, adapt and strengthen resilience.

Read more: Source: The Global Risks Report 2016, World Economic Forum

#risks2016

Source: World Economic Forum, Global Risks 2016

As in previous years, assessments of risks in this year’s Report are based on the Global Risks Perception Survey. The survey captures the perceptions of almost 750 experts and decision-makers in the World Economic Forum’s multi-stakeholder communities and was conducted in Fall 2015. Respondents are drawn from business, academia, civil society and the public sector and span different areas of expertise, geographies and age groups.

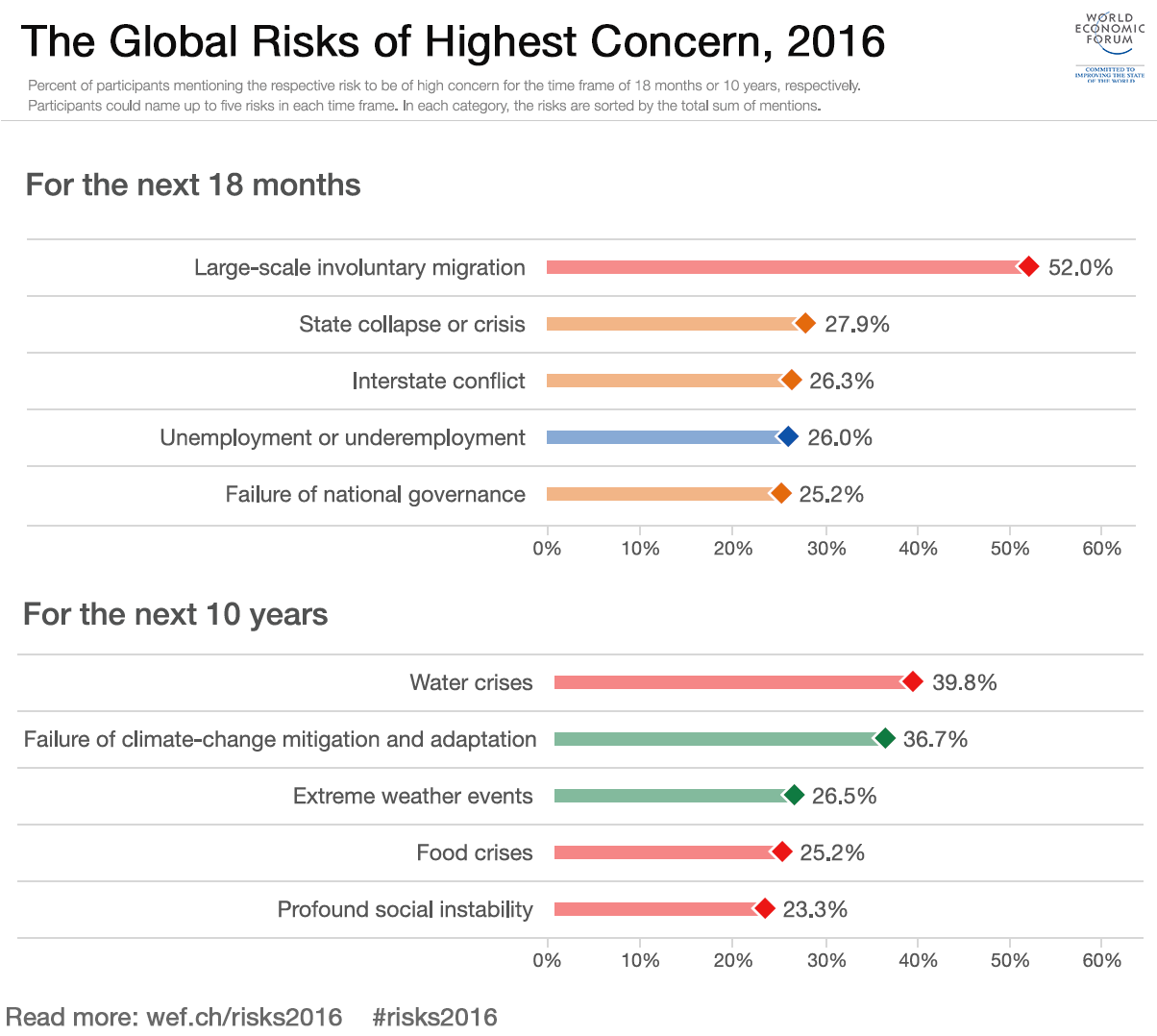

To tease apart short- and longer-term thinking and shed light on the psychology behind the responses, the survey asked experts to nominate risks of highest concern over two time horizons: 18 months and 10 years. Global risks that have recently been in the headlines – such as large-scale involuntary migration, interstate conflict and cyberattacks – tend to feature higher as short-term concerns, indicating that recent events significantly influence our thinking about risks and, hence, stakeholder action.

The longer-term concerns are more related to underlying physical and societal trends, such as the failure of climate change mitigation and adaptation, water crises and food crises. Interestingly, extreme weather events and social instability are considered a concern in both the short and long term, reflecting an expectation that the frequency and intensity of crises will continue to rise. One of the roles of this Report is to raise awareness about the importance of long-term thinking about global risks – especially significant when it comes to attempting to limit the extent of climate change and to adapt to the change that is already inevitable.

Three risk clusters are discussed in more detail: the cluster linking the failure of climate change mitigation and adaptation with water crises and large-scale involuntary migration; the cluster linking large-scale involuntary migration with a range of risks related to social and economic stability; and the cluster linking economic global risks with uncertainty around the impacts of the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Coping with the changing climate

Read more: Source: The Global Risks Report 2016, World Economic Forum

#risks2016

Source: World Economic Forum, Global Risks 2016

Climate change and water crises, which have featured prominently in the Global Risks Landscape over the last five years, are joined this year by largescale involuntary migration. The links among these risks appear clearly in the Global Risks Interconnections Map 2016 (Figure 2 below), and the intertwined challenges are unfolding against a background of many socio-economic pressures.

As illustrated by the Global Risks Interconnections Map, climate change and water risks are intricately linked to food security concerns – a subject explored further in Part 3 of the Report. About 70% of the world’s current freshwater withdrawals are used for agriculture, rising to over 90% in most of the world’s least-developed countries. Carbon dioxide also causes ocean acidification, which makes it harder for small shellfish to form the calcium carbonite shells they need to grow – with implications rising up the food chain, threatening the availability of food from the seas as well.

Challenges around water management are already immense. On the one hand, over a billion people lack access to improved water. Some 2.7 billion – or 40% of the world’s population – suffer water shortages for at least a month each year. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and 2030 across Asia. Globally, based on current trends, water demand is projected to exceed sustainable supply by 40% in 2030. Adding to the pressures, agricultural production will have to increase in the coming decades to feed a growing population and a rising demand for meat.

Unless current water management practices change significantly, many parts of the world will therefore face growing competition for water between agriculture, energy, industry, and cities. Tensions are likely to grow within countries, especially between rural and urban areas and between poorer and richer areas, and also potentially between jurisdictions. More than 60% of the world’s trans-boundary water basins lack any type of cooperative management framework. Even where such frameworks do exist, they often do not cover all states that use the basin. Interstate tensions over water access are already apparent in some parts of South Asia, and could impact the evolution of the international security landscape, as discussed in Part 2.

Climate change will only exacerbate these challenges. The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, in November 2014, reaffirmed that this warming in the climate system is “unequivocal” and that human influence is “extremely likely” to be the dominant cause. Atmospheric concentrations of three major greenhouse gases (carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide) are at their highest level in 800,000 years, with CO2 concentration up 13% since 1990. The world today is estimated to be about 1°C warmer, on average, than it was in the 1950s, and the effects are being felt. Regional analysis of the Global Risks Perception Survey shows that declining water availability features as the most likely risk in the Middle East and North Africa and South Asia, and the likelihood of extreme weather events is considered especially high in North America, South Asia and East Asia and the Pacific.

Scientists caution that a total warming of 2°C implies a high risk of catastrophic climate change that could damage human well-being on a global scale. Yet even if each country meets its Intended Nationally determined Contributions plans, submitted to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and agreed at the Paris Climate Conference in December 2015, warming is projected to reach 2.7°C by 2100.

Given these developments, it will, therefore, be impossible to live without adaptation – but adaptation planning is complicated by the difficulty of predicting not only the expected degree of warming but also the expected pace. One source of uncertainty is the Arctic feedback loop – will ice sheets collapse slowly or rapidly? The average sea level is already rising by 3 millimeters per year, faster than any other time in the last two millennia; many of the world’s cities lie on the coast or on river banks, with poor neighborhoods most likely to be in low-lying areas vulnerable to flooding. Another source of uncertainty is the “Amazon Dieback” scenario: recent oscillation between unusually dry years and heavy flooding could be an early indicator of irreversible system phase change. If the Amazon stops absorbing carbon and starts releasing the estimated 120 billion tons of carbon it holds – equivalent to 15 years’ worth of 100% fossil fuel emissions – the impact will be global.

Failure to address climate change and water crises will forcibly displace more people – the IPCC warns that droughts and coastal floods could cause “large-scale demographic responses – for example, through migration”. Forced displacement is already at an unprecedented level, causing severe humanitarian challenges, as explored more in the Report.