What is managed retreat, and is it a viable response to climate change?

Climate resilienceArticleMay 23, 20248 min read

Managed retreat is often considered a measure of last resort. But is it now time to consider it as a sensible option in response to rising sea levels, eroding coastlines, flooding and other climate risks?

New Zealand’s first national adaptation plan includes most of the climate resilient options you would expect to find. Nature-based and hard-engineering solutions, such as wetlands and sea walls, feature prominently. As do upgrades to properties and infrastructure to withstand more extreme weather events and initiatives to educate and prepare communities for climate risks.

But a section in chapter five of the plan stood out when it was unveiled in August 2022. Entitled “Adaptation options” – but what grabbed attention is that the rest of the title read: “including managed retreat.”

Managed retreat – also called managed realignment – involves the strategic relocation of people, buildings and other assets from areas vulnerable to climate change and natural hazards. It is not a new concept, but New Zealand’s plan has put it back in the spotlight.

The phrase “managed retreat” was first used by coastal engineers in the early 1990s as a response to sea level rise in Essex, UK. Today it is considered by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the European Climate Adaptation Platform Climate-ADAPT as a credible solution to global sea level rise, which could impact up to 410 million people by 2100. For instance, the low-lying Pacific island nation of Kiribati bought land in Fiji in 2014 to allow a future migration if rising sea levels make their islands uninhabitable.

In some cases, managed retreat includes mechanisms such as “setbacks” that either require new development to be a minimum distance from the shore or restricted in density. But the concept of retreating whole communities is gaining credence.

“Given the current situation of climate change, it is not a question of whether communities will retreat, but rather where, when and how some of them will retreat,” says Michael Szönyi, Climate Director at the Z Zurich Foundation, who believes managed retreat is a viable option. “In the past there was a long tradition of abandonment or managed retreat due to environmental or economic changes, such as drought or a loss of industry.

“But there may be a need to revive this tradition,” he adds. “It is not sustainable to build ever larger sea defenses or levees along vast stretches of coasts or rivers. Other options will need to be considered. In some cases, managed retreat may even become a necessary response to the impacts of climate change in the decades ahead.”

Managed retreat is not only a potential response to coastal flooding and sea level rise. The village of Matatā in New Zealand, for instance, pursued managed retreat due to flash flooding from nearby hills. Meanwhile the town of Valmeyer, Illinois, relocated due to the impacted of inland flooding caused by the Mississippi River (see box below).

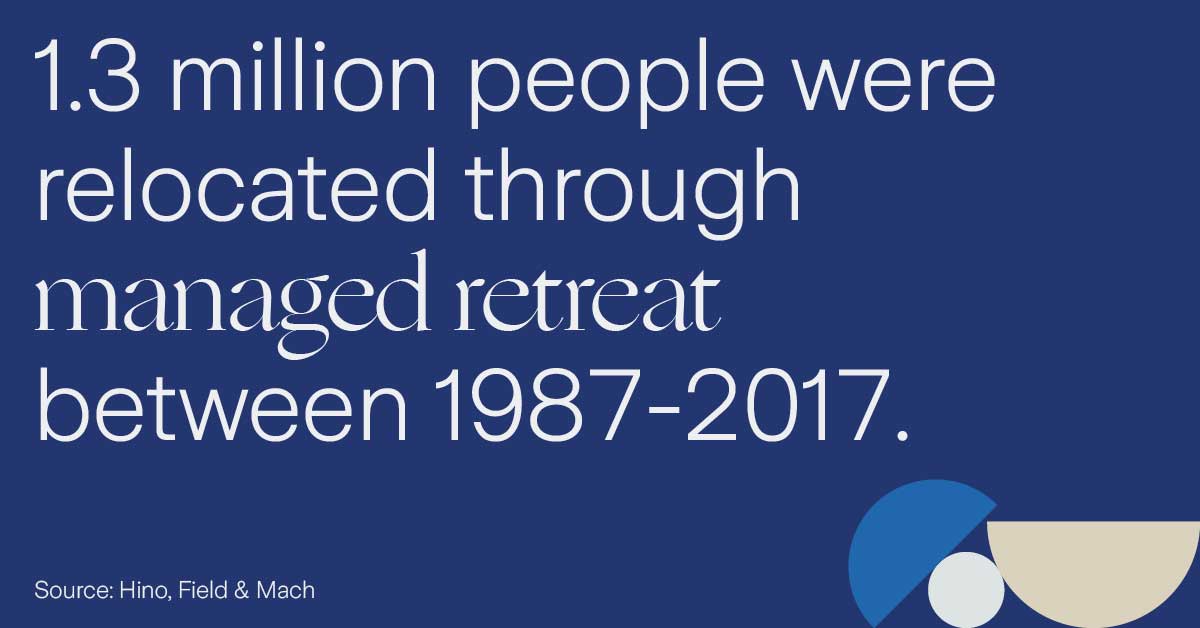

A 2017 study, which analyzed 27 cases of managed retreat in 22 countries, found that about 1.3 million people have been relocated through managed retreat over the past three decades. This was in response to natural hazards including tropical storms, erosion, earthquakes and tsunamis.

Examples of managed retreat

The coastal village of Matatā in New Zealand was engulfed in slurry, rocks and timber in a massive debris flow caused by flash floods coming down from the surrounding hills in May 2005. It destroyed 27 homes and damaged 87 other properties. The regional council was unable to find any viable engineering solutions or early warning systems that could mitigate the risk, so it opted to pursue a managed retreat in 2012.

In summer 1993, the farming community of Valmeyer, Illinois, was flooded twice in a month when the swollen Mississippi River topped its levee system. The floodwater lingered for months, damaging 90 percent of properties. Faced with rebuilding the town and risking further flooding, the 900 residents instead decided to use funding – including assistance from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) – to rebuild an entire town “New Valmeyer” on higher ground a mile away.

Due to the threat of rising sea levels and storm surge, the coastal village of Fairbourne in west Wales, UK, will need to adopt a policy of “managed realignment” between 2025 and 2055. It will require the relocation of properties, businesses and 850 residents. The area will then be turned back into a tidal salt marsh.

The challenges of managed retreat

But people are not easily relocated from their homes. They build close attachments to their property, local culture and community, which can cause social and psychological difficulties – particularly if it involves loss of cultural heritage or moving a family from their ancestral lands. Even the term “managed retreat” to some people sounds like you are accepting defeat or giving up on a community – and that can be difficult to internalize.

The retreat of communities also involves a huge financial cost. Compensation is often paid to residents and property owners. Local economies can be damaged if, for example, fishing communities are moved farther away from the ocean. All these challenges – ethical, logistical, financial and legal – make it difficult for local and national governments to take decisions that could be considered controversial or politically perilous.

Retreating from a megacity

It is one thing moving a small town or village; it is another when you try to undertake a managed retreat from a megacity. But that is what Jakarta – Indonesia’s capital city – plans to do.

Jakarta is one of 570 coastal cities vulnerable to a sea level rise of just 0.5 meters by 2050. An issue compounded by severe land subsidence – caused mostly by excessive groundwater extraction – that is causing parts of the city to sink.

This is why in 2019, the Indonesian government announced plans to move its capital to East Kalimantan on the island of Borneo to a new city called Nusantara. In the first out of five phases until 2045, development is focused on the core government area of Nusantara that will host a population of 1.2 million by 2029.

Although it is not an official managed retreat, the move would help relieve pressure on Jakarta and potentially enable people in the worst affected areas on the coast to resettle.

“Even in a dire situation like that in Jakarta, you do not need to abandon the whole city,” says Szönyi says. “Some cities could undertake a partial managed retreat on some of its land on the coast to create a wetland area, such as mangroves. That would not only move people to safety living in those areas; it could also provide more natural flood spaces that can help the rest of the city’s population.”

Forced retreat

Despite some of the controversy that surrounds the concept of managed retreat, many communities are already in a forced retreat. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), an annual average of 21.5 million people have been forcibly displaced by weather-related events – such as floods, storms, wildfires and extreme temperatures – since 2008.

The plight of climate refugees shows us that climate change does not only pose an immediate threat to people and property due to a destructive hurricane or wildfire. Climate change is also a long-term danger that is already destabilizing societies and economies. It can reduce water availability and water quality, increase the spread of disease and raise the likelihood of drought leading to crop failures that may reduce incomes and cause hunger.

“The need to take conscious decisions about managed retreat will inch closer,” Szönyi says. “Climate change is already altering the size and direction of migration flows. Instead of people being forced into an unplanned relocation, strategically moving people and their assets through managed retreat may be a better policy. Faced by climate change, our survival depends on changing our ways of life, including where we live.”

Climate Resilience

Our Climate Resilience experts help you identify and manage climate risks, and prepare you for climate reporting.