As temperatures rise, so do geopolitical tensions

Climate resilienceArticleSeptember 23, 20246 min read

Combating climate change requires co-operation and cooler heads, not conflict.

In the 1950s, the town of N’guigmi, which sat on the banks of Lake Chad in Niger, was the region’s largest fishing community. By the mid-1970s, droughts had changed this. The shores of the lake had retreated and were now 85 kilometers away, pushing the local community into precarious economic conditions.

A study by Camilla Carlesi of the Council for European Studies found that the government’s inability to support communities around the Chad Basin has led to growing social unrest, eventually pushing many young men toward radical groups such as Boko Haram.

These are not the problems of any single country. The World Bank estimates that by 2050 climate change is likely to have created around 143 million climate migrants globally, many of them traveling across borders.

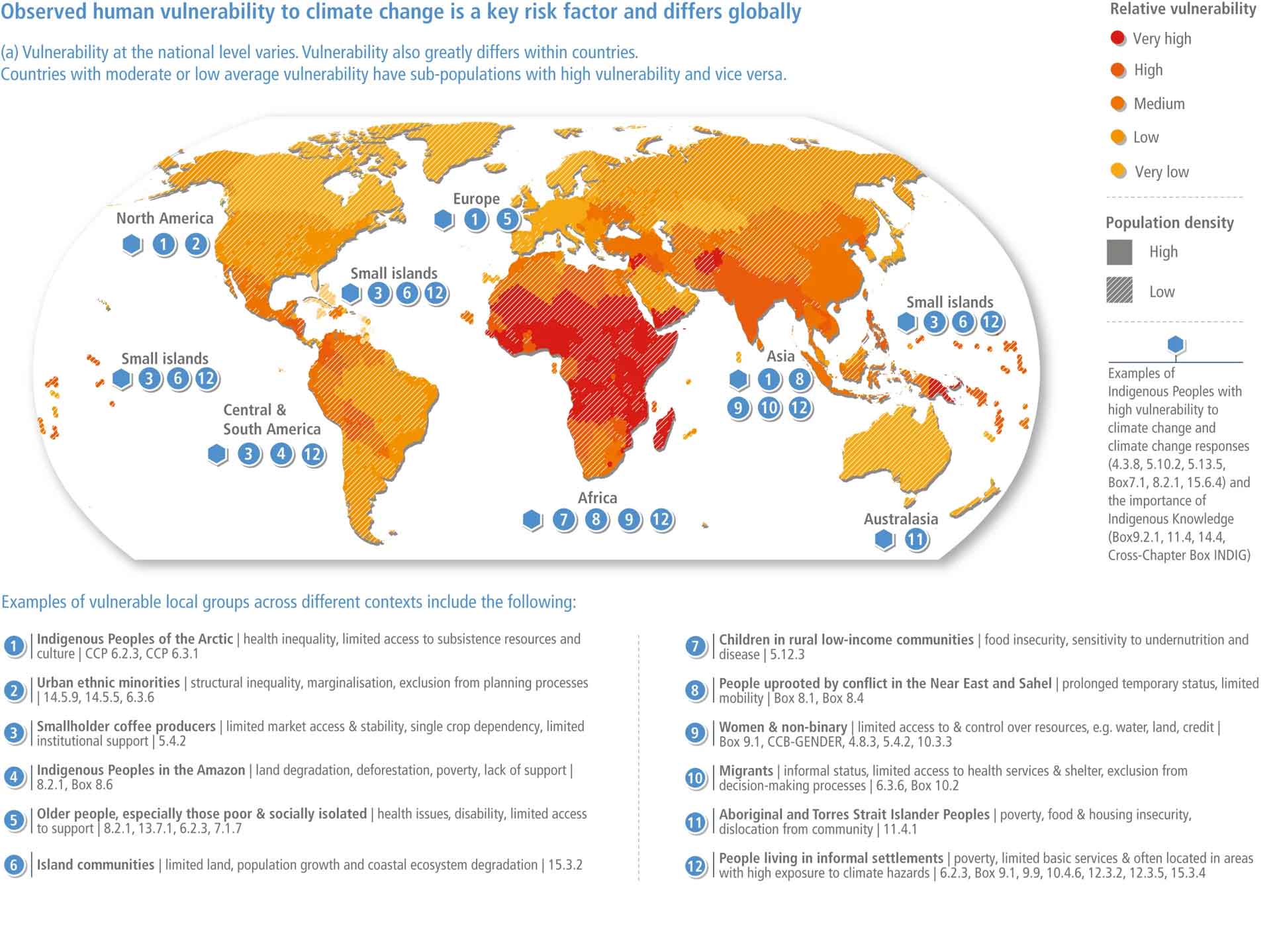

“If you look at the IPCC [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] report published in 2022, it shows that about 40 percent of the world’s population lives in areas that are highly vulnerable to climate change,” says Penny Seach, Chief Underwriting Officer at Zurich Insurance Group. “This means that there will be mass displacement over time, and any mass displacement is going to strain resources and infrastructure in receiving areas.”

In the most climate-vulnerable regions, rising tensions are just one part of a much larger geopolitical picture. Take the Bay of Bengal, which extends more than 2,000 kilometers along the coast of Southeast Asia from India to Indonesia. As sea levels have risen nearly 30 percent faster than the global average, communities across the region have frequently clashed over the distribution of aid.

With sea levels expected to rise by as much as 10–12 inches along the US coastline by 2050, this is not just an Indo-Pacific problem. Insurers are already working with companies and governments around the world to build longer-term physical, economic and social resilience to climate change.

“We had a customer with a big manufacturing plant who suffered in excess of USD100 million in damage after a flood,” says Seach. “We paid on the claim, but we also helped bring together other stakeholders to find a solution. There’s a community that surrounds the company that’s just as vulnerable, so by bringing the local municipality together with our client, we were able to build resilience in the area.”

Building resilience to extreme climate events also requires wholesale energy transition. Countries that rely on oil and gas imports will remain exposed to market volatility, while companies and communities hooked into centralized grids risk losing power during increasingly frequent extreme weather events. Yet the energy transition itself raises further geopolitical risks.

Grim medicine

For countries such as Nigeria, where oil exports make up 90 percent of foreign exchange earnings, the shift toward clean energy sources constitutes a significant economic threat.

To manage this threat, governments and companies need to be focused on adaptation, explains Seach. “This is what insurance companies do well – assessing the risk, preventing the risk, taking action and mitigating that. This framework helps companies and governments focus on bringing investment to build economic resilience.”

Such a framework also helps companies to develop financially sustainable strategies. In 2020, Zurich established Zurich Resilience Solutions, which brings together climate data, customer information and Zurich’s in-house expertise to build tailored risk management models for companies. With access to industry-wide data, this service has helped clients to quantify their risk levels and benchmark their resilience strategies against others facing similar threats.

A more dynamic understanding of the energy transition helps to determine where geopolitical tensions are likely to rise. The scramble for lithium and other metals used in the manufacture of batteries has already engendered conflict with indigenous communities across resource-rich areas. Research by the Institute of Development Studies found that over half (61) of the 120 mineral mining projects across Chile and Argentina are currently in conflict with indigenous communities.

With the battery chain – from mining through to recycling – projected to grow by 27 percent annually to 2030, developing transition strategies that mitigate these risks is essential. “Understanding both physical and transition risk can help determine whether you need to pivot to build resilience into your business model,” explains Seach.

It also provides a more accurate picture for governments looking to develop multilateral partnerships. In 2023, Denmark extended a partnership with Bangladesh to develop strategies to strengthen both countries’ resilience to climate change, as well as providing €4.7m in insurance for loss and damage in relation to climate disasters.

“This is what I think the value chain should be at a global scale,” says Kent Jackson, Design Partner at architecture giant Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, where he also co-leads the practice’s Climate Action Group. “At present, we work in our own little sector or country, but by breaking down these boundaries, we can execute projects that genuinely benefit everyone.”

One of the most potent symbols of climate co-operation is Africa’s Great Green Wall. Stretching 8,000 kilometers across the continent, the project brings together governments and businesses from multiple countries to restore 100 million hectares of degraded land. The project, which will sequester 250 million tonnes of carbon and create 10 million jobs by 2030, is not only integral to slowing down climate change, but an example of how we can improve economic resilience in the process.

But it is not just Africa where these projects need to take root. “In the global north, we’re seeing a lot of this change occurring incrementally, which isn’t enough to change behaviors,” says Jackson. “There needs to be policy driving change, versus everyone coming together organically.”

This is an opportunity for companies to lead, Jackson says. Investing in key technologies can help companies build their own resilience, while forming strategic partnerships with other companies, research institutions and governments can create new avenues for revenue generation.

As global warming accelerates, proactive adaptation and collaboration across sectors will be crucial in mitigating the effects of climate change and ensuring a sustainable future for all. It should have started a long time ago, warns Jackson. There is no more time to delay.

This article was originally published on Economist Impact.

Climate Resilience

Our Climate Resilience experts help you identify and manage climate risks, and prepare you for climate reporting.