Taking responsibility for biodiversity loss

Climate resilienceArticleMarch 3, 20206 min read

Interconnectivity risks mean biodiversity is not a niche concern – every business has a part to play.

Mention the cinchona tree to the average CEO and you will most likely be met with a quizzical look. “What does a tree have to do with my business?” they may reasonably ask.

Yet the cinchona is more than that. It is a symbol of the biodiversity loss crisis which has placed the planet on the cusp of a sixth mass extinction – and this time the blame lies squarely at the feet of humankind.

The south American tree is the source of the malaria drug quinine. Its bark has been used as medicine for millennia, while South American liberator Simon Bolivar adopted it in Peru's coat of arms. But now it is facing extinction as vast swathes of forest are chopped down to make way for plantations.

And that link – between business and biodiversity loss – cannot be dismissed. Biodiversity loss may be the invisible aspect of the environmental emergency – compared to wildfires, floods and extreme weather events – but it is every bit as important.

“You can't just look at direct risks,” says Eugenie Molyneux, Chief Risk Officer of Commercial Insurance at Zurich Insurance Group. “You have to look at the interconnected risks because your impact may be more far reaching than you might think.”

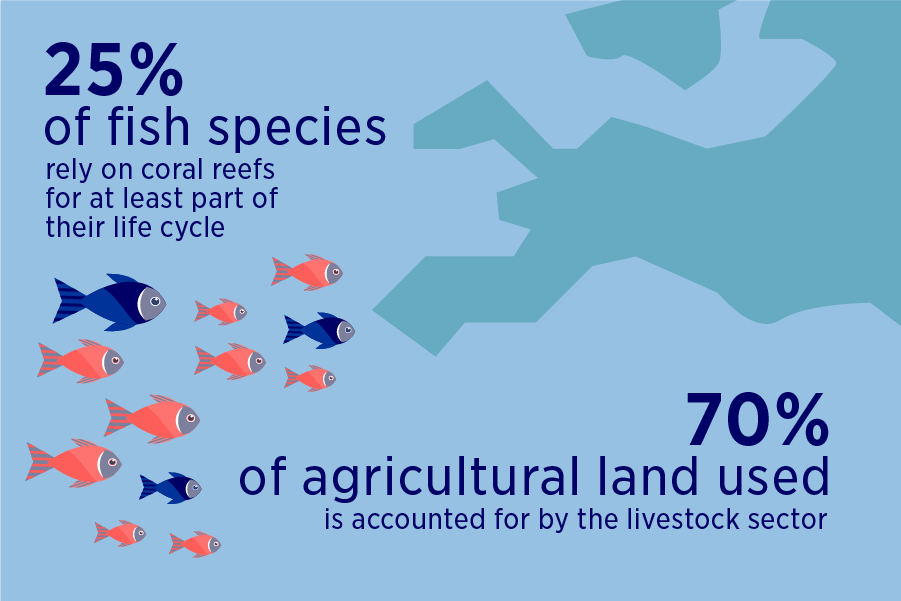

“Take a shoe manufacturer, for example. They may think biodiversity loss has nothing to do with them but where do they get their leather? Is their supplier clearing forest to raise animals? Was there an impact on biodiversity as a consequence?” Consider the fact that 70% of agricultural land is dedicated to livestock and the scale of the issue is clear.

“The way to reduce biodiversity loss is by changing your practice.”Eugenie Molyneux, Chief Risk Officer of Commercial Insurance at Zurich Insurance Group

The interconnected risks to businesses are legion, beginning with the operational problems biodiversity loss can trigger. Resource dependency, scarcity and quality is directly linked to biodiversity – especially for the food and fishing industries.

Then there are reputational and market risks for companies not taking biodiversity loss seriously, for example those linked to shareholders’ pressures or changes to consumer preferences. The global consumer revolt against single use plastics following Sir David Attenborough’s Blue Planet TV series is a prominent example of how sales can be affected overnight by public sentiment.

Consumer preferences are a major subject. According to the Union for Ethical BioTrade (UEBT) Biodiversity Barometer 2018, a majority of consumers expect companies to respect biodiversity, but do not trust them to do so. As public awareness grows, there is an increased risk of consumer boycotts, such as those of bluefin tuna and palm oil.

For companies, financial risks are exacerbated by the potential for higher insurance costs, difficulties securing finance and depreciation of assets. But it is in the arena of liability risks – the potential for legal suits – that the most pressing threat lies.

“Just as a company can be sued for polluting a water supply, it’s not a long bow to draw that a similar litigation could be applied to biodiversity loss,” adds Molyneux. “Imagine this rather extreme scenario: a company builds a plant in a remote location and local farmers experience declines in their crop yields.

“The nexus is then made to lower crop pollination, through a lower population of insects and birds - and ultimately to the timing of the company building its plant. Why is that form of environmental damage not the same, in principle, as polluting their water? “Even if the nexus is not proven legally, this is where reputational risk becomes a factor for the company.”

Indeed, the risk of legal suits founded in biodiversity may increase as disclosure and external reporting on companies’ biodiversity impact assessments increases. Yet nature-related risks remain undervalued in business decision-making.

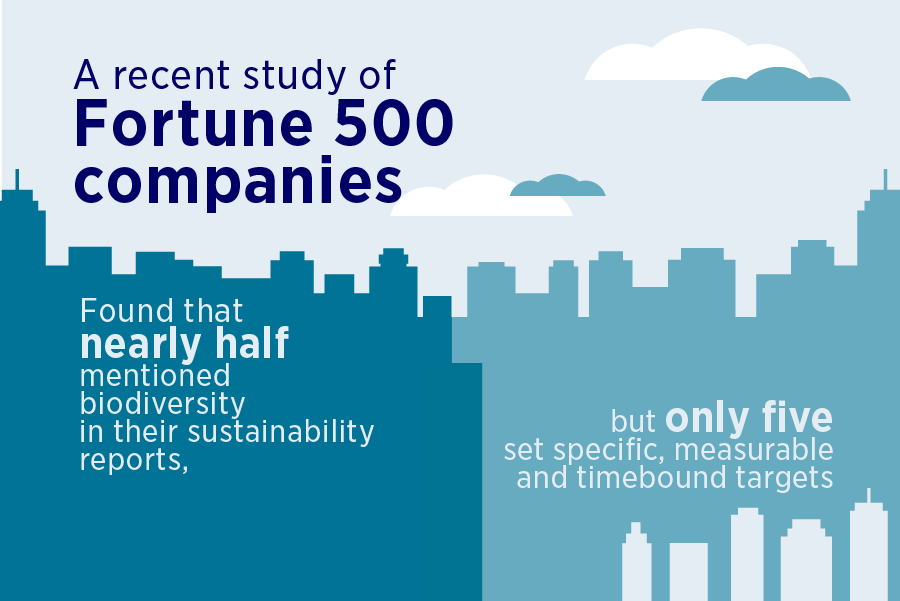

As noted in the Global Risks Report 2020, produced by the World Economic Forum in collaboration with Zurich: “All businesses should account for ecological risks to their operations and reputations, yet few do. A recent study of Fortune 500 companies found that nearly half mentioned biodiversity in their sustainability reports, but only five set specific, measurable and timebound targets.”

There is, however, still time for businesses to take action to halt – and even reverse – biodiversity loss.

“The way to reduce biodiversity loss is by changing your practice,” concludes Molyneux. “The starting point is to carry out a total risk assessment, assessing the areas where your company has an impact.”

“That means looking across your supply chain, where your resources come from, and making changes to mitigate your impact on biodiversity loss.”

“This is an issue for every single one of us – businesses, governments and individuals – and everyone has to play their part. Organisations like Zurich Insurance Group have the resources to help guide businesses through the risk assessment and mitigation processes, so we can make a real difference.”

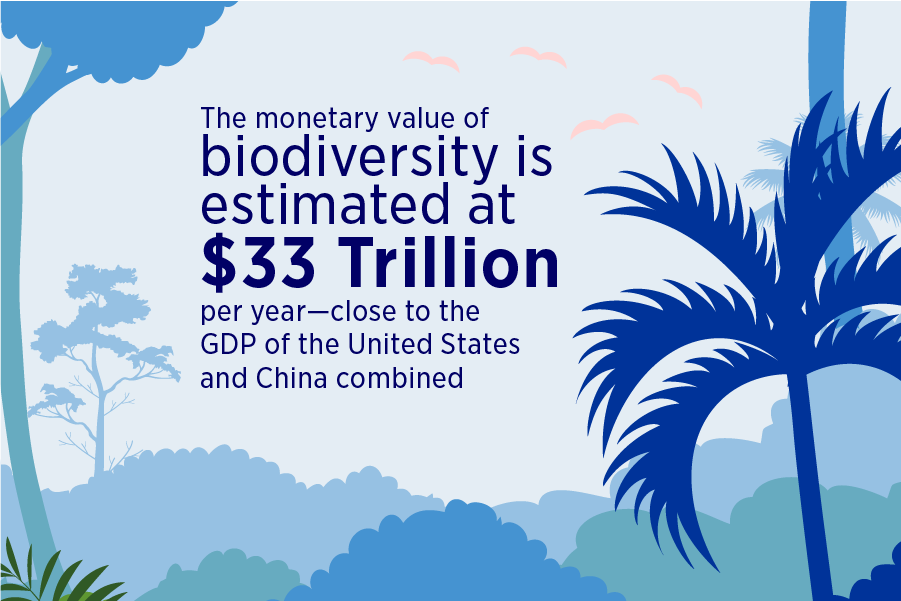

The motivation to take swift action on biodiversity is compelling. There is a growing body of evidence that biodiversity loss and the warming planet are mutually, destructively reinforcing – each exacerbating the other. The higher the level of biodiversity in the ecosystem, the more successfully it can adapt to change.

Meanwhile, there are plenty of opportunities available to companies which act responsibly on their biodiversity impact. There is growing interest in the areas of organic food and drink, ecotourism, eco fibres in the textiles and fashion industries.

Meanwhile the year 2020 has been designated a “super year for nature”, when the global community will rededicate itself to halting biodiversity loss with a 10-year action agenda, in a plan scheduled for agreement at the conference of the parties to the UN Convention on Biodiversity (CBD) in Kunming in China in October.

Ethical forest management has the potential to act as the backbone for sustainable economies, while pharmaceutical companies are dedicating increasing resources to remedies found in natural resources.

Meanwhile one Singaporean firm has begun producing artificial shrimp in the laboratory – a sustainable challenge to the controversial prawn farmers who raze biodiversity-rich mangroves, leaving coastal regions vulnerable to flooding.

As the Global Risks Report 2020 points out, the preservation of biodiversity is an important measure to manage climate transition risk. By applying climate resilience adaptation strategies to assess their positions and come up with solutions, there is still time for the world’s businesses to prevent catastrophe.