Will climate change dry up our supply chains?

Climate resilienceArticleApril 6, 2021

There is concern that droughts could cause some of the world’s most important rivers to become unnavigable leading to the loss of vital inland shipping routes. Should we be worried and how should we respond?

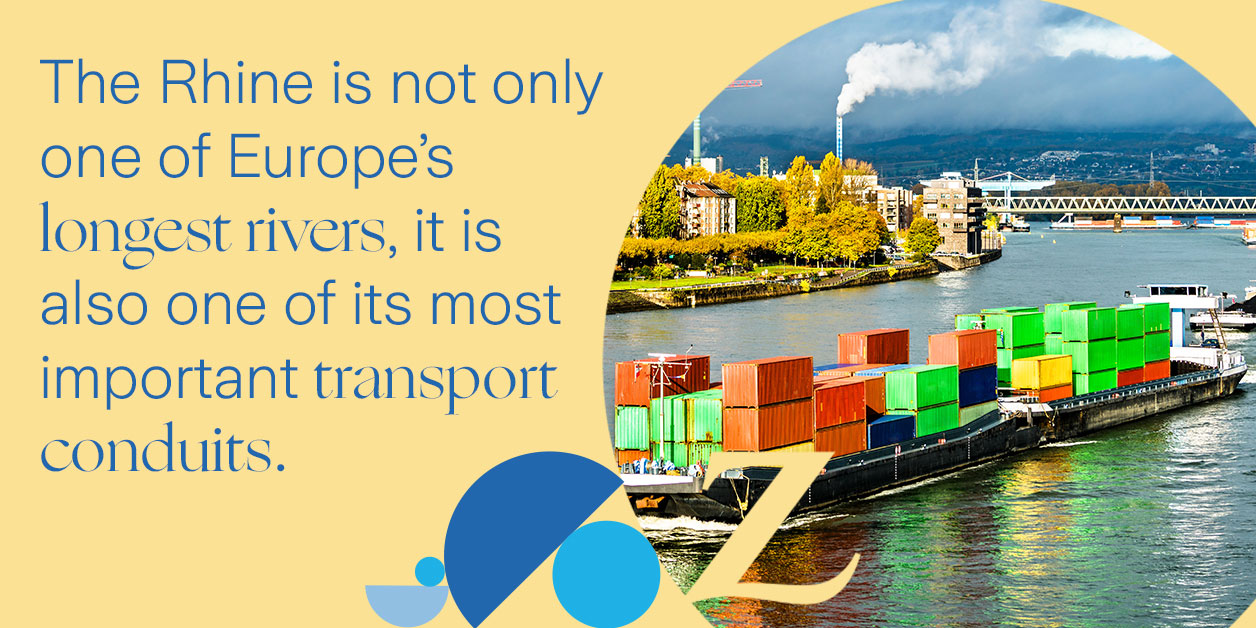

The Rhine is not only one of Europe’s longest rivers, it is also one of its most important transport conduits. Flowing from its source in Switzerland, it winds 800 miles (1,200 km) through some of the continent’s most important industrial zones before emptying into the North Sea at Rotterdam. It is a key inland shipping route that is vital for transporting chemicals, petroleum products, iron ores and other industrial raw materials.

But it’s under threat. At the end of 2018, following one of the longest dry spells on record, parts of the Rhine were at record-low levels for months. This made the river unnavigable for large cargo barges causing a 27 percent year-on-year fall in transport on the Rhine in the third quarter of 2018.

It had a major impact on all industries that use the river for transport purposes. Many resorted to road and rail alternatives or smaller barges. But ultimately, these actions were not enough.

Switzerland, for instance, had to release diesel and gasoline from its strategic reserves due to supply interruptions. Meanwhile, German chemical giant BASF had to halt production due to raw material shortages, which lowered 2018 earnings by around €250 million. In total, it is estimated the decline in Rhine traffic caused a €5 billion loss in German industrial output in the second half of 2018.

The frequency, duration and severity of droughts is expected to rise across most of Europe this century, so we could see more disruption on the Rhine. Climate change could also adversely impact trade on other inland waterways around the world, which is set to reach USD 2,250 billion by 2024.

One of the world’s most important inland stretches of water – the Panama Canal – is already struggling with drought. In February 2020, canal operators were forced to adopt new water-saving measures to sustain an operational level of water in the 50-mile (80 km) canal that transports about USD 270 billion worth of cargo every year between the Pacific and Atlantic oceans.

This was in response to rainfall in 2019 that was 20 percent below the historic average for the canal region. It followed several years of lower than average rainfall coupled by a 10 percent increase in water evaporation levels due to a 0.5-1.5°C rise in temperature. It led to record low levels at Gatun Lake, the main source of water that allows the canal to operate during dry seasons.

Mississippi River Blues

The Mississippi River in the U.S. has also suffered from disruption due to drought over the past decade. In June 2012, water levels on lower stretches of the 2,320-mile (3,730 km) river fell so low that fully loaded barges were at risk of running aground. The average barge’s cargo capacity fell by about 300 tons – a loss of more than 7,000 tons per 24-barge tow – and led to a flurry of emergency dredging by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

It is not just a decrease in rainfall that is causing concern. The Rhine’s flow, for instance, is heavily influenced on long-term reserves of water in the Alps. Melting snow and glaciers feed the river and are particularly important in the drier summer months. But climate change threatens to dwindle these natural reservoirs as summer melting out paces ice formation in winter.

According to research led by ETH Zurich, half of the volume of the Alps’ 3,500 glaciers will be lost by 2050 due to global warming already caused by past emissions. After that, even if carbon emissions plummet to almost zero, two-thirds of the glaciers will still have melted by 2100 – this will have a big impact on future water availability.

“Too much water can also be a problem,” adds Amar Rahman, Global Lead for Climate Resilience at Zurich Resilience Solutions. “I’ve seen the Rhine rise to levels where there’s not enough clearance under bridges for barges to pass. On other rivers, floods and severe weather can cause barges to break from moorings and for navigation to become dangerous.”

Water: A planet-friendly transport conduit

If inward waterways are disrupted, then it will exacerbate climate change as waterborne freight is more environmentally friendly than road or rail alternatives.

According to American Waterways Operators, one inland barge can hold 27,500 barrels (bbl) of liquid cargo, equivalent to 46 rail cars or 144 tanker trucks on the road. It means an average inland barge emits 15.6 grams of carbon dioxide (CO2) per ton-mile compared to 21.2 grams for rail freight and 154.1 grams for truck freight – almost 10 times higher.

The Panama Canal also makes a big contribution. By offering a shorter route for ships, it reduced CO2 equivalent emissions by 13 million tons in 2020. That is equivalent to 2.8 million passenger vehicles driven for a year.

This happened on the 3,900-mile (6,300 km) Yangtze River that connects Shanghai with China’s inland cities. It flooded in the summer of 2020 when heavy rains swelled water levels and caused parts of the river to become unnavigable, which delayed the global supply of vital personal protective equipment.

“Due to climate change, we will likely see more water level fluctuations and severe weather events impacting our rivers. This will undoubtedly cause more disruption to supply chains reliant on inland waterway transport,” adds Rahman.

Resilience over efficiency

So how can we minimize potential disruption to these supply chains?

One obvious response is to design new, flatter barges and ships that can operate at lower water levels, or by developing more sophisticated locks and dams to ensure minimal water levels.

But industries that rely on these inland waterways will also need to prepare better for potential disruption. This could include, for instance, investing in long-term forecasts that provide early warnings of water level fluctuations.

“Climate change is not the only issue. Supply chains have become optimized for efficiency rather than resiliency, which makes them more vulnerable if river levels fall,” says Björn Hartong, Zurich’s Global Risk Engineering Practice Leader for Marine & Security.

It is not just inland waterways at risk from a changing climate, says Hartong. On a more regular basis he is seeing temperature extremities disrupt rail lines, wildfires close airports and floods damage key road links.

“Businesses need to assess their supply chain’s exposure to physical climate risks, then adapt and strengthen areas that are vulnerable. For instance, investing in holding more safety stock in case part of the supply chain is interrupted by poor weather. There is a cost involved and a possible loss of efficiency, but it will be an investment in certainty and ultimately customer satisfaction,” adds Hartong.

But remember, rivers are not just transport highways. They also provide irrigation for farmers and water for industrial production and cooling, they can generate clean electricity, and our vital ecosystems for fish and other aquatic fauna, as well as providing water for human use.

Yes, our supply chains will need to adapt to future changes in these inland waterways. But let’s also mitigate these changes by caring for our rivers and our planet.