Part II

The 1980s

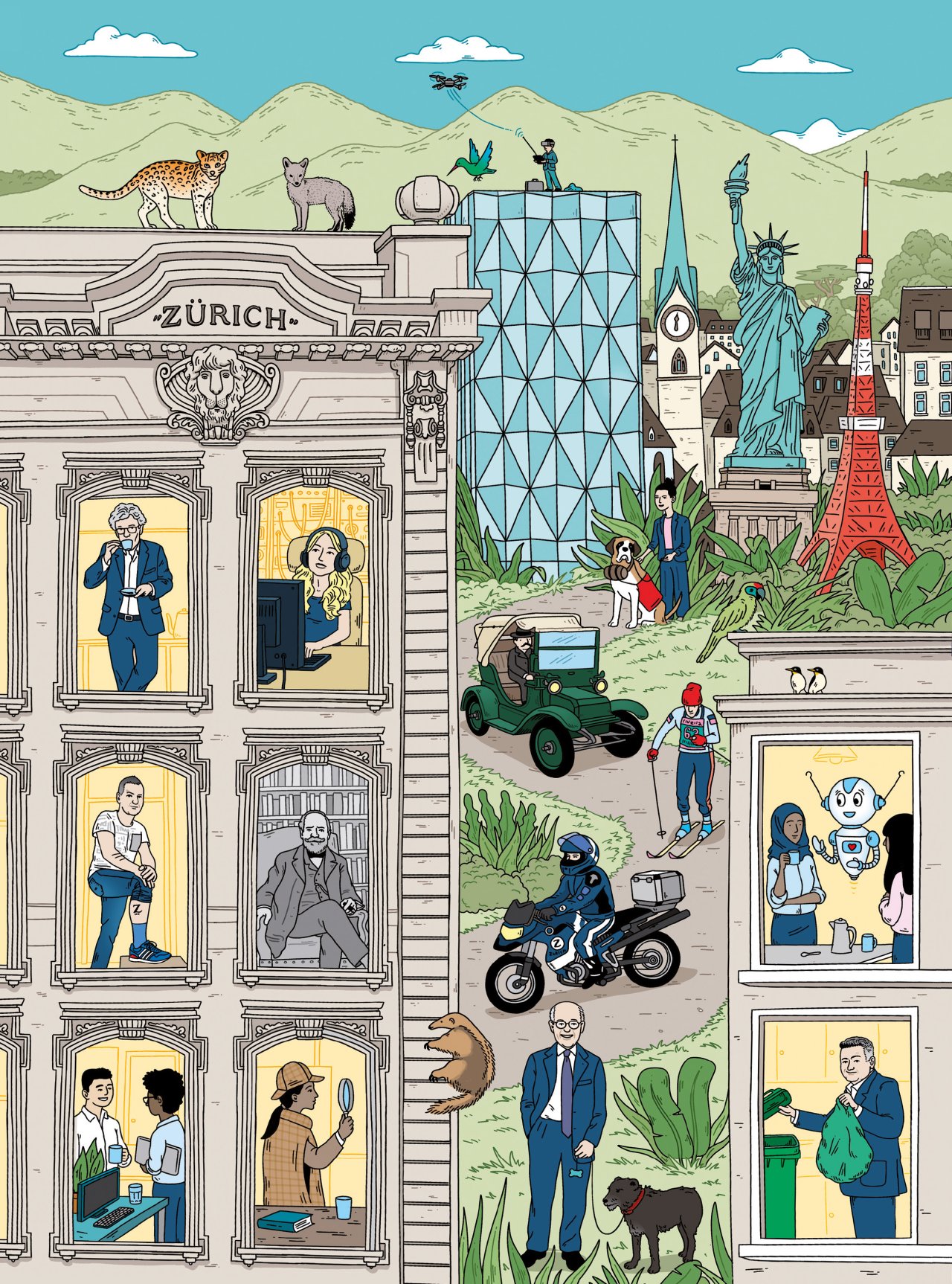

Zurich, the city and the company, is often known in clichés by those on

the outside. Staid, reserved, orderly. As Zurich employees, we know this

isn’t true, right? And Zurich, the city, was in an irascible mood in the

early 1980s. In fact, the city was burning, or as those years are known

locally from a well-known documentary, ‘Züri brännt.’ Students and young

people battled with police over funding for alternative arts spaces. It

started outside the opera house on May 30, 1980, and spread to the other

main thoroughfares around town over the coming months: Bellevue,

Limmatquai, Bahnhofstrasse. Windows were shattered, cars burned, tear

gas was used by the police, scores were injured, one person was killed,

and thousands were arrested.

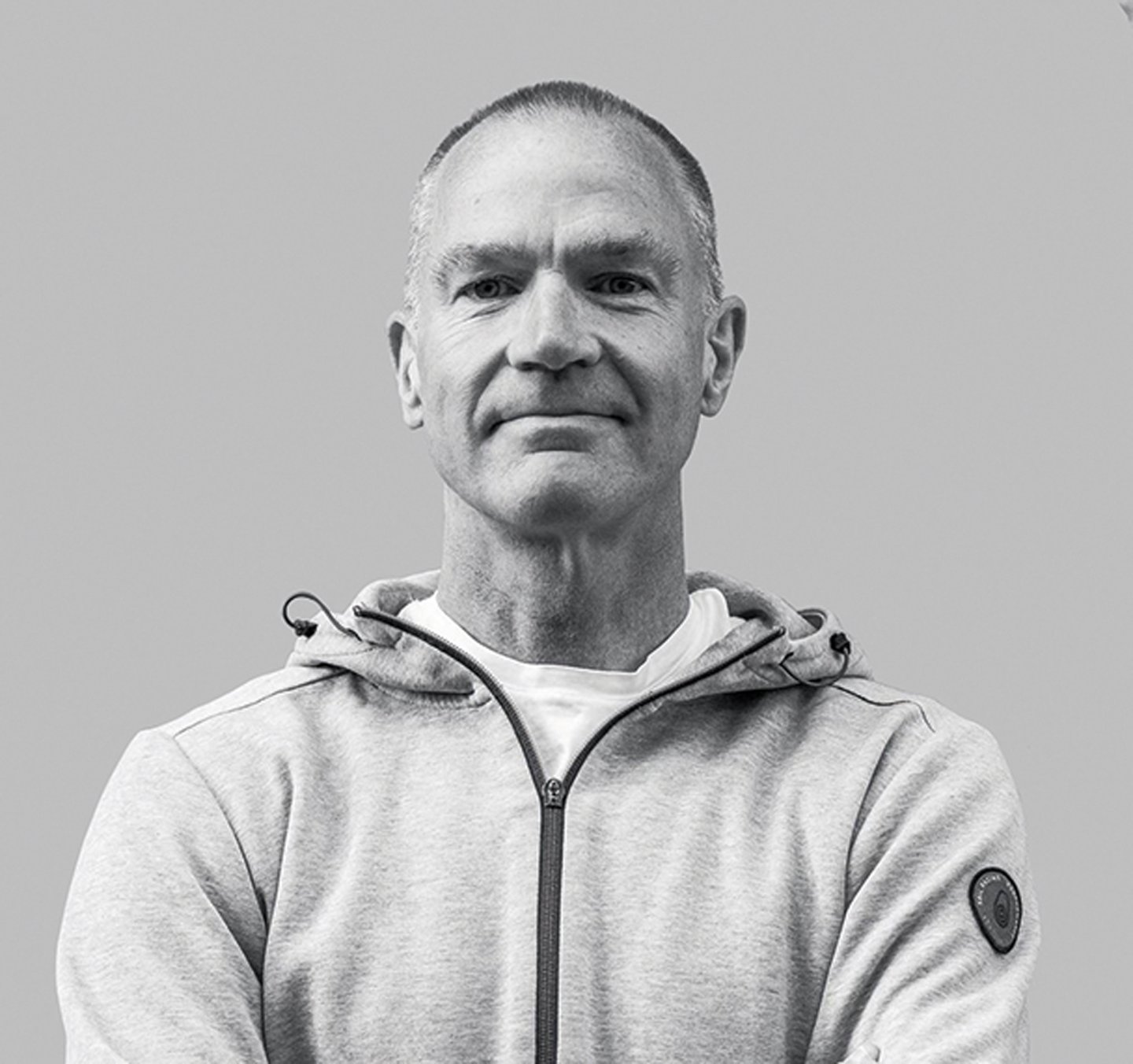

Bruno Pfister was caught in the middle, metaphorically but also

literally. In November of 1979, the 21-year-old started at Altstadt

(acquired by Zurich three years later) in customer service, but before

that he had considered a career in the police force.

“It was a different culture back then.”

On his first day, the general conditions guidelines were dumped on his

desk, and he couldn’t make heads or tails of it. “Is this job right for

me?” he wondered. The people seemed nice enough, he recalls – and yes,

they smoked in the office – but it was all Sie (you, formal) not du

(informal). “It was a different culture back then,” says Pfister, now a

senior product manager. “Today in the Oerlikon office, it’s always du.”

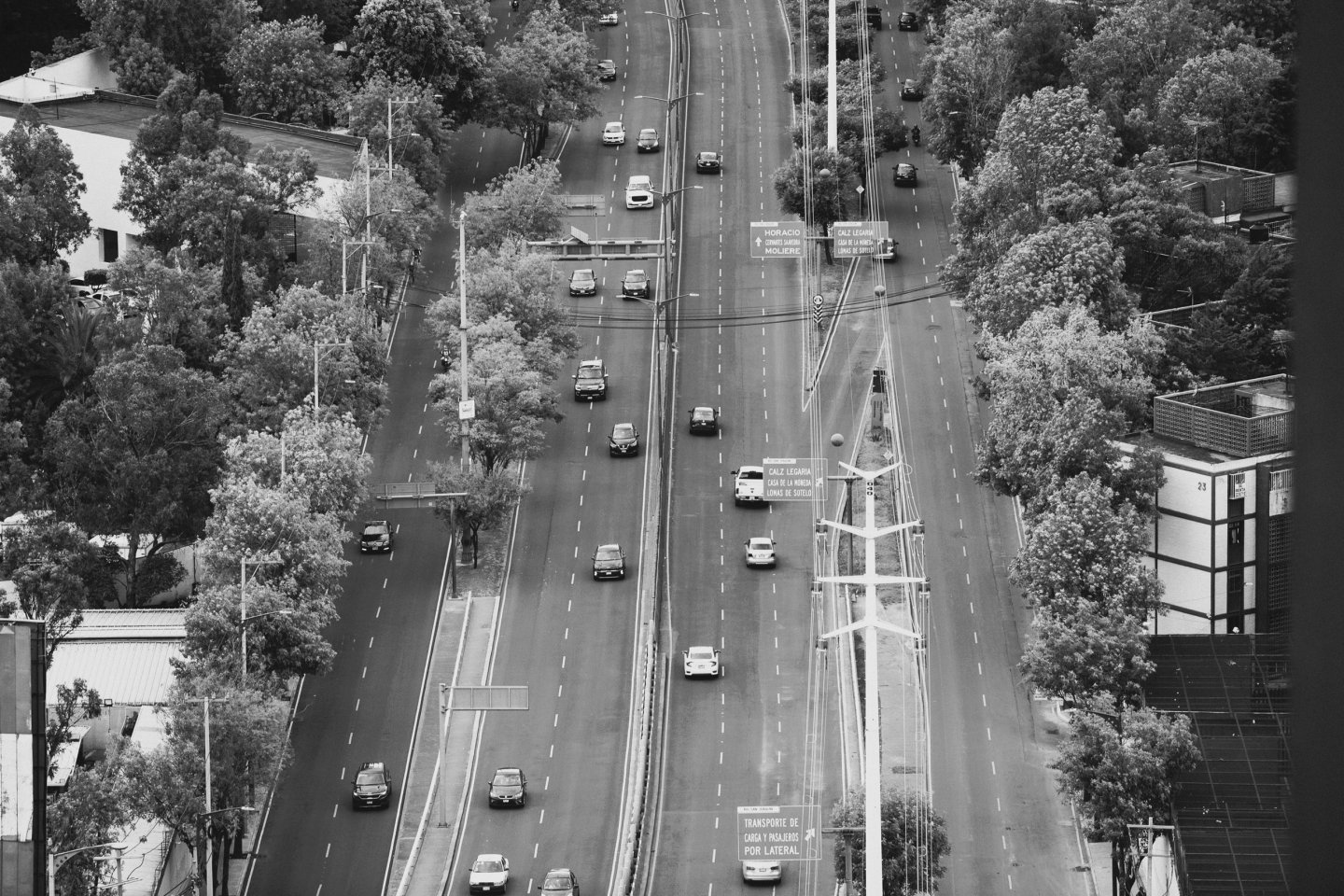

Out in the streets in 1980 and ’81, the language wasn’t formal or

informal, just angry. While driving home after work one evening, Pfister

was confronted by a police water cannon on Quai Bridge, one of the most

beautiful spots in Zurich. He had to swerve into the tram lane, and then

had to be careful not to run over the large stones that were scattered

everywhere.

A few weeks later, while heading to a movie, he was faced with police on

his left and protesters on the right. He ducked into the theater just in

time. “It was better for my health,” he says. “I knew people in the

youth scene, and it was not so nice to hear what our police were doing.”

At the same time, he didn’t like the approach of the protesters. “I

don’t think that’s the way to solve problems.”

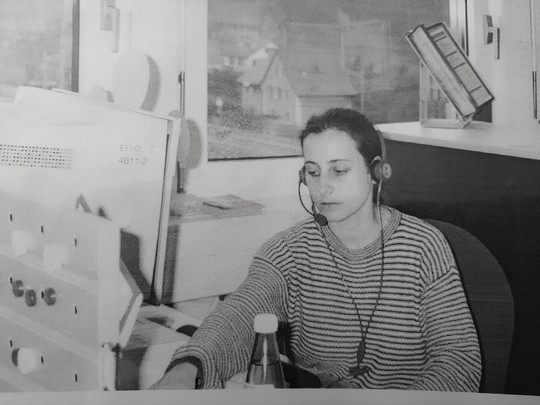

Anita Blom-Pozdnik steered clear of the riots altogether. She may have

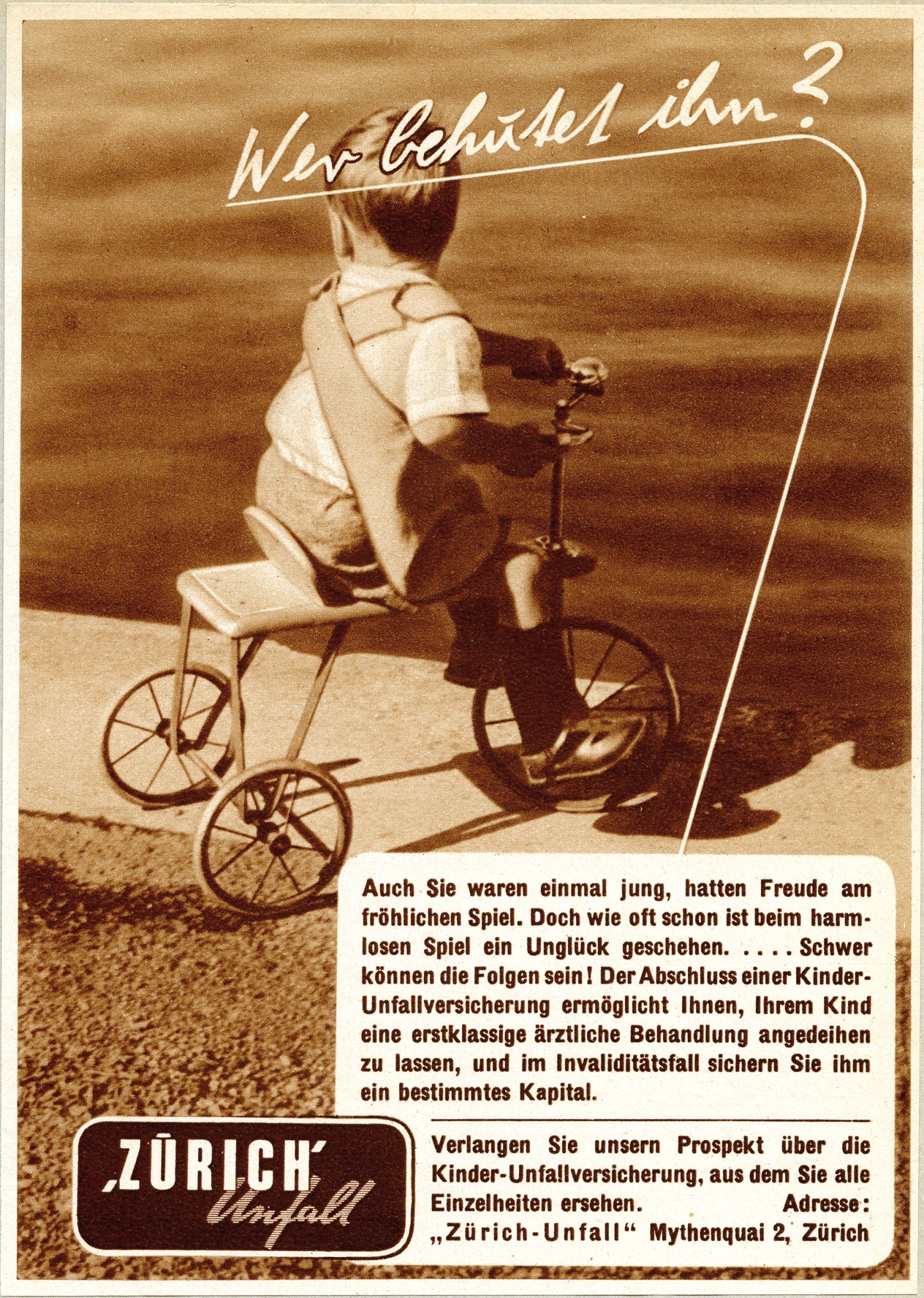

started her apprenticeship at Zurich, in the main Mythenquai office, on

April 21, 1980, nine days before the movement began, but she was a mere

14 years old. Plus, she had protective parents, especially her mother,

who “had a lot of fear about everything.” They told her the protesters

were up to no good and that she should come straight home to Thalwil, a

few towns outside the city limits. “It was a conservative environment,”

she says.

The young Anita was happy Zurich took her aboard. A prominent Swiss bank

wouldn’t on the basis that she was an Austrian citizen. And although she

didn’t know much about the company, her father had insurance with Zurich

and a sales agent named Ernst Blättler would visit their home once or

twice a year. “He was friendly and helpful and knowledgeable,” Anita,

now a business performance analyst, remembers. “My father trusted him so

much that he told us if something should happen to him, we should get in

touch with Mr. Ernst Blättler and ask him for support. I can still

picture him.”

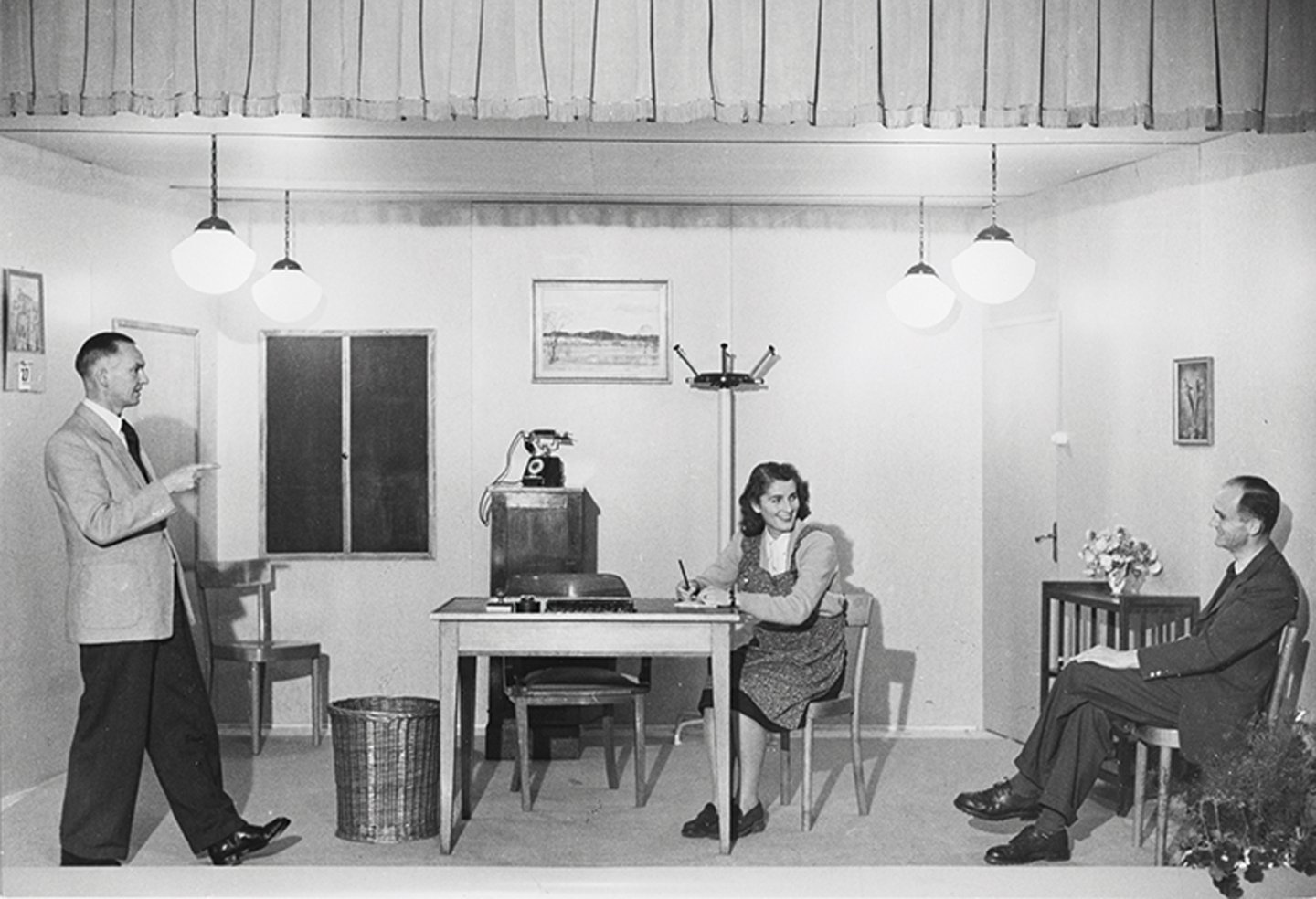

She was, like many 14-year-olds, shy and nervous. “I was in awe, like

‘Wow, everything is so big.’ ” With that, she noticed, came hierarchical

distinctions within the office – and mostly in the hands of men. In

titles, but even in signs and gestures. Normal workers, in her

recollection, had chairs without armrests, while managers had armrests –

and their own canteen. Different desks, curtains and carpets also

conveyed levels of importance.

When Anita turned 15, she committed a gaffe. Her boss asked her to bring

a paper to a director for a translation and then added, “Tell him to

improve his handwriting so I can read it.” So Anita handed the director

the paper and relayed the message. He looked at her aghast. “Did she

really say that?” he asked Anita. Yes, she said, and when Anita got back

to her boss’s office, she was proud to tell her that she passed on the

message. “No, please tell me you didn’t. That was just a joke.” Her boss

thought it could have severe consequences. It didn’t. “And his

handwriting was better from that day on.”

In the following years, there were odd comments and ‘jokes’ along the

lines of, “Oh, I’m sick, but if you were laying at my side, I’d feel so

much better.” She says, “It was nicely meant in a way, but misguided.”

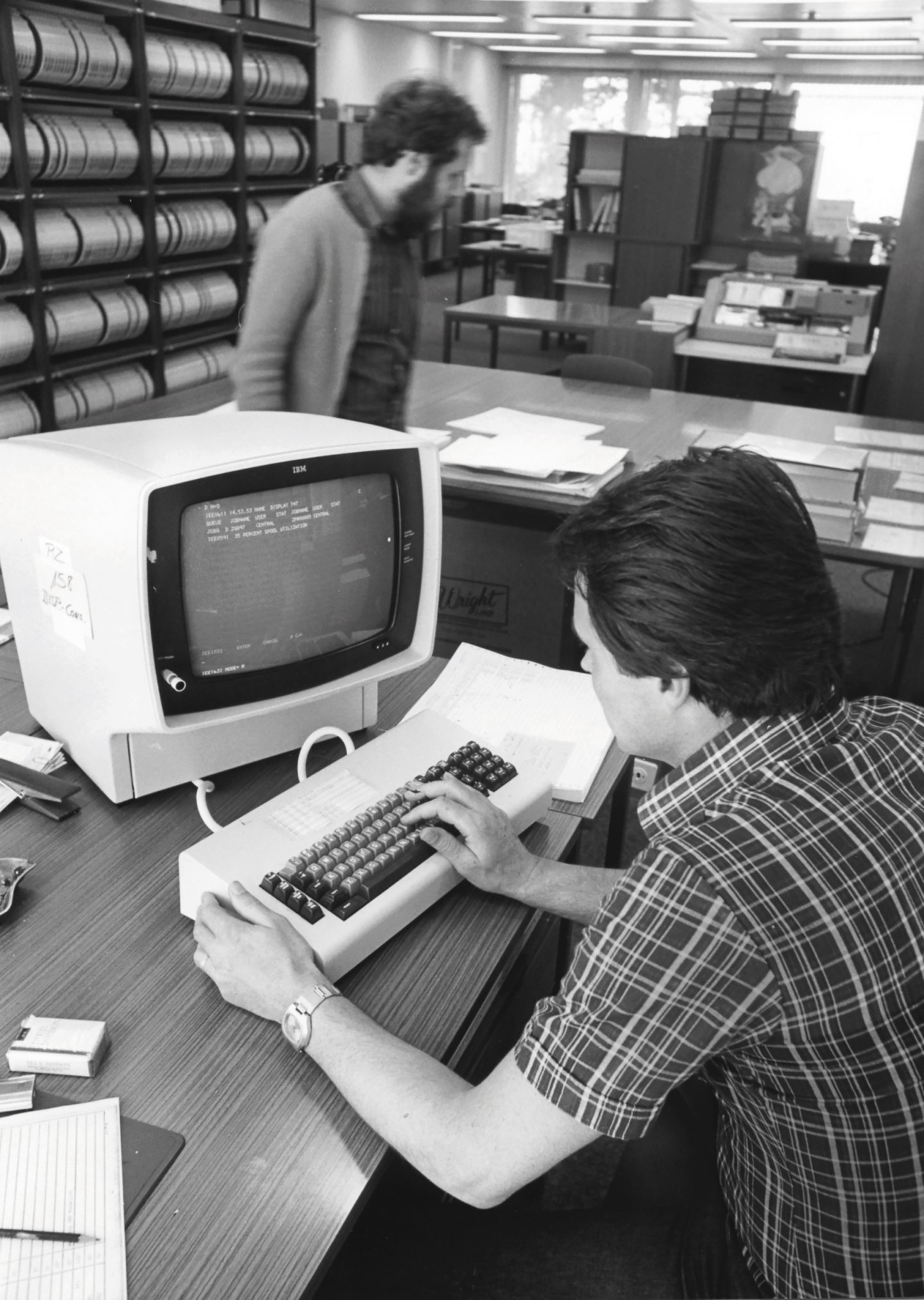

“He couldn’t believe that a woman could program.”

What was even worse, in her opinion, was always being considered a

secretary – even if she was one of the best apprentices, with the

highest scores – while the young men had more interesting opportunities.

Finally, she said, “ ‘I’m sorry, but I’m much better than this. I’ll be

wasted in this job.’ They said, ‘That’s all we have,’ and I said, ‘I

don’t believe that.’ I was appalled.” And when word got out, other

departments did want her, since she had developed a reputation as a good

worker. Even later in the mid-1980s, when she was 19 and met with

someone to discuss a new task she was supposed to program, he asked her

several times if she was really the programmer and not the secretary.

“He couldn’t believe that a woman could program,” she says. When she

originally wanted to cut back to 80 percent, she was questioned whether

she could still lead her small team. She remembers company parties where

male employees could bring their partners, but women couldn’t.

Things have changed a lot since then, Anita says. And she’ll always

fondly remember how Zurich supported her during her advanced education.

She went to school full-time and was still able to work for the company

at 50 percent, putting in those hours on semester breaks and weekends.

The company was also supportive when she had children and worked

part-time. “Zurich offered me possibilities to combine my education and

my family life,” she says. “Plus, I had really good bosses, and I liked

my work so it made it easy to stay.”

Dublin wasn’t burning on June 8, 1981, Paul Croghan’s first day at Irish

National, which would eventually be absorbed into Zurich, but there was

unrest. The previous year saw 350,000 stream into the streets of the

Irish capital to protest high taxation rates. There were strikes, high

unemployment and a ‘brain drain’ among young people.

The 20-year-old Paul had been working, but he still felt particularly

lucky to get this job, which appeared secure. “And wasn’t I right,” he

says today. He was, and still is, in reinsurance underwriting, but back

in 1981, his direct colleagues all had worked together since 1952. “So

you had to break into this very settled circle,” he says. “People had a

very different attitude toward their colleagues back then. They were

more like family. Sometimes they actually were family. There was a

culture, at least in Ireland, of people getting their family into the

company. That doesn’t happen so much today.”

His first salary was 48 pounds a week, but his rent was 25 pounds. Do the

math: He had 23 pounds a week to live on. So he’d go to the local pub –

Horse Show House – rather than put the heat on in the apartment. “It was

my sitting room.” And one that was popular with colleagues.

It added to the familiarity in the office. One woman was known as Ms.

Tipp-Ex because she used the correction fluid to fix typing mistakes.

“It wasn’t in any way insulting, and she embraced the name,” according

to Paul. “Another colleague whose real name was Eamon was always called

Benjy because he looked like a popular TV soap opera character, and he

wasn’t insulted because many of us were better known by our work

nickname. But now if I told a colleague that I was going to call them

something that’s not their name, I don’t know how they’d respond. Now

it’s more businesslike and formal.”

“You know what, if that car crashes, and they all get killed, I’m the

manager tomorrow.”

In his early days, senior staffers would take off during the day for

Leopardstown Racecourse to bet on the horses. They didn’t appear worried

that there was no one in the office to cover. One day, Paul was standing

outside the office when a carload of them left for the track. His young

co-worker, with a bit of macabre humor, said, “You know what, if that

car crashes, and they all get killed, I’m the manager tomorrow.”

The combination of familiar and formal showed up in other ways. Shirt and

ties weren’t enough for men; you had to wear a jacket as well. And even

shoes had to conform. “Sometimes men would wear shoes other than black,”

Paul says, “and, I’ll never forget, they would get a tap on the shoulder

from their manager who would say ‘Never brown in town.’ In other words,

you should be wearing black shoes.”

Barbara Knost in Germany remembers a casual and collegial workplace in

the 1980s – and, she says, one that was “unbearably hot in the summer

since we were on the fourth floor under a copper roof in the old

building on Bonn’s Talweg.” There was never a dress code and, she adds,

“It was like a big family with the trainees integrated directly….The

annual company party was always good and contributed to the working

atmosphere. On Friday afternoons, we ended work early and ate and drank

together.”

The ’80s ended with two earthquakes, a literal one and another of the

geopolitical variety. At 5:00 p.m. on October 17, 1989, Vicki Trindade

was driving home from the Farmers Insurance office in Pleasanton,

California – east of the Bay Area – to her home in Tracy over the

Altamont Pass.

Traffic was light that night since it was about a half hour before the

start of Game 3 of baseball’s World Series, which was being played,

coincidentally, between the San Francisco Giants and the Oakland A’s for

the first time ever. In fact, live coverage of Game 3 from Candlestick

Park had just gotten underway on national TV. At 5:04, the video on ABC

began to break up and the legendary announcer Al Michaels, losing his

famous cool, said “I’ll tell you what, we’re having an earth….” And the

signal went off. When the audio portion of the broadcast returned

shortly thereafter, he said, in typical California showtime-style,

“Well, folks, that’s the greatest open in the history of television, bar

none!”

Vicki wasn’t a baseball fan, not at all, and during her drive home she

didn’t feel the magnitude 6.9 quake centered to the southwest in Santa

Cruz that killed 63 people, injured over 3,000 others, and caused

widespread damage. But when she heard about it on the car radio, she

says, “I was terrified something might have happened to my baby daughter

back home.” It didn’t. “The next day at work was unusual,” says the

senior commercial underwriter who started in 1971. “We had to pick up

hundreds of files that fell off the shelves and rearrange the items on

our desks. Luckily, no one was hurt and damage was very minimal in the

office. But it was really strange. We never experienced such a strong

earthquake.”

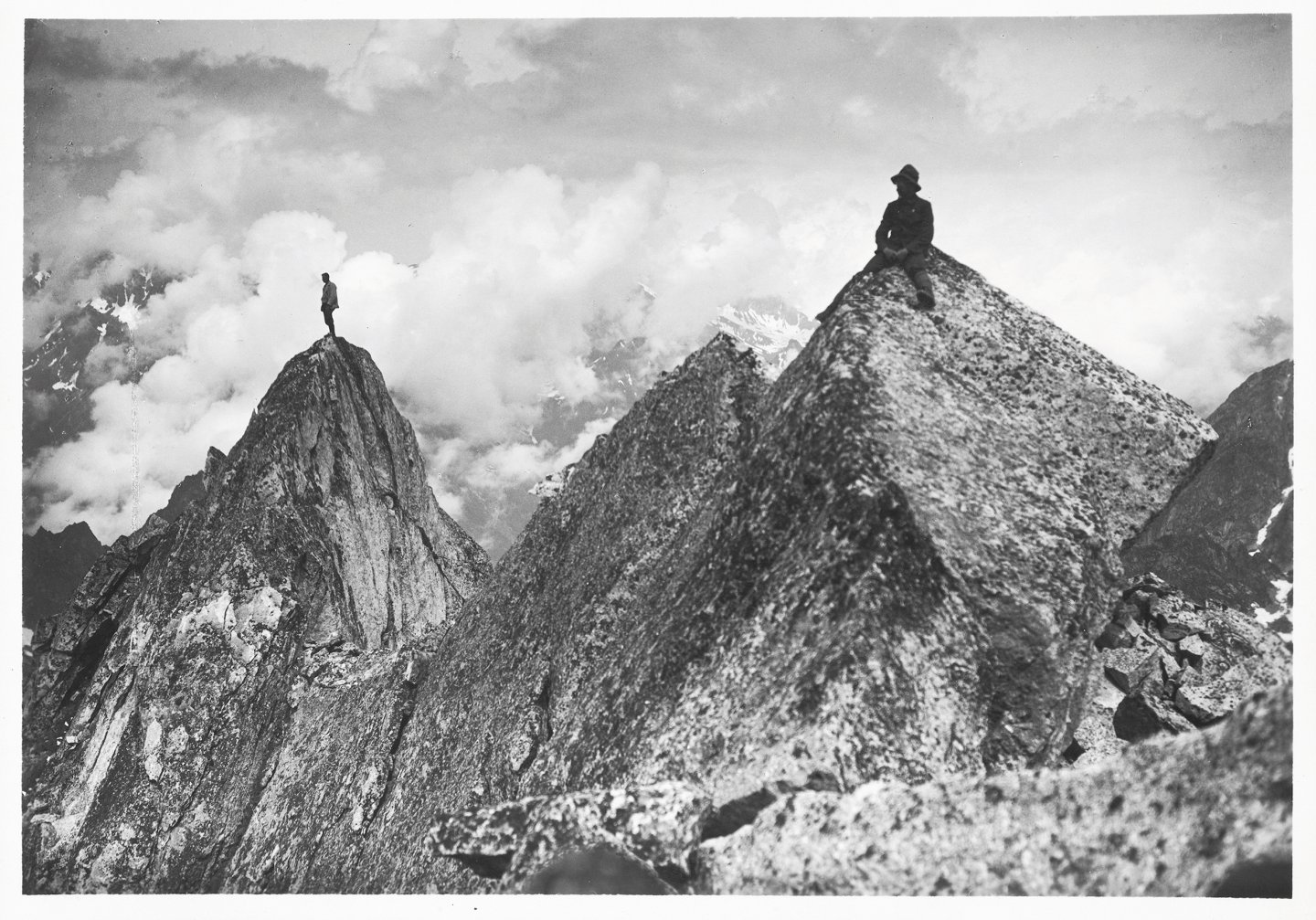

“I could not have imagined that the Wall would fall 10 years later.”

Three weeks later, on Thursday, November 9, there was a tectonic shift

geopolitically: the Berlin Wall came down. “I can’t remember what was

said between my colleagues,” says Angelika Metternich of the Köln

office, “but at the beginning of my training in 1980 at Deutscher Herold

[soon part of Zurich] I could not have imagined that the Wall would fall

10 years later.”

“Everyone was surprised that the opening of the border took place so

quickly,” says Klaus Baldeweg, an international service team leader who

started in 1980 in the Frankfurt office, which at the time was beside

the old opera house. “We were all happy about the ‘new’ Germany but were

aware that reunification meant a huge financial effort. Nevertheless,

the euphoria among the population was very great.”

“I had a flexiday on November 10, and so was only able to speak to my

colleagues the following week,” says Ute Stammel, who started in the

Köln office in 1977. “Most thought it was good, but of course there were

also naysayers.” If not everyone was moved at the time, the aftershocks

are still being felt today, more then 30 years later.