Understanding the growing risk of wildfires – from Hollywood to the Arctic

Climate resilienceArticleJune 13, 2025

The catastrophic L.A. wildfires were a highly visible reminder of the devastating power of wildfires. As experts warn of an increase in wildfire frequency and severity, there’s an urgent need for better preparedness and resilience.

In January 2025, the world watched in horror as wildfires raged through Los Angeles. The fires engulfed the suburbs of Palisades and Eaton, destroying homes, businesses and community facilities.

Wildfires are not a new phenomenon. Yet seeing them in the shadow of the iconic Hollywood sign and devastating the homes of A-list celebrities was a shocking reminder of their destructive power.

The L.A. wildfires razed about 16,000 hectares (40,000 acres) of land. A tiny area compared to the 152 million hectares (376 million acres) of tree cover that were lost globally to wildfires from 2001 to 2024 – an area equivalent in size to Mongolia. Last year, 2024, was the worst on record with 13.5 million hectares (33.5 million acres) lost to wildfires.

Wildfires not only cause extensive environmental damage, including the destruction of habitats, loss of biodiversity and the release of carbon into the atmosphere, they also destroy homes, livelihoods and entire communities. Even those not directly impacted can suffer from respiratory and cardiovascular issues due to smoke inhalation. Additionally, the destruction of trees and grasslands increases the risk of flooding and mudslides in downstream and downhill communities, as these natural barriers that would have absorbed rainfall are removed.

The economic costs are also significant. According to a study by the Los Angeles County Economic Development Corporation, property losses from the L.A. fires are estimated between USD 28 to 54 billion. Business disruptions are expected to cost up to another USD 8.9 billion in lost economic output over the next five years. Additionally, there are costs associated with employment losses (up to USD 3.7 billion) and lost tax revenues (up to USD 1.4 billion).

Worse to come?

The concern is that we could see many Hollywood-style sequels to the L.A. wildfires in the years ahead. According to the UN Environment Programme, the number of wildfires is expected to increase by 30 percent by the end of 2050 and by 50 percent by the end of the century. As temperatures rise, more moisture will be drawn out of soil and vegetation to create tinder-dry conditions that fuel fires. These fires can spread at incredible speeds, especially if winds are strong – like the Santa Ana winds in Southern California.

“We have seen wildfires increase in intensity and destructiveness in recent years,” says Nicolette Botha, Head of Climate Resilience and Sustainability Asia Pacific at Zurich Resilience Solutions. “Wildfire seasons are starting earlier and finishing later each year across the globe, impacting areas that were once considered risk-free. In the face of this growing risk, businesses, communities, and individuals need to better understand wildfires and learn how to prepare, respond, and recover from them.”

Canada is already experiencing an upsurge in wildfire activity. From 1990 to 2022, an average of 2.5 million hectares (6.2 million acres) of forest area burned each year. But in 2023, Canada experienced its worst year on record with nearly 7,000 wildfires torching over 17 million hectares (42 million acres) of land – almost seven times the average.

In 2024, 5.3 million hectares (13 million acres) were scorched, more than double the 1990-2022 average. This year, the 2025 wildfire season could be set to repeat the 2023 record-setting season due to a warm and dry spring that has ignited the second-worst start to the wildfire season on record.

Even Canada’s Arctic region is now under regular threat. According to the NOAA Arctic Report Card, wildfires in Canada’s permafrost region in 2023 burned more than twice the area of any previous year on record. More frequent and severe fires, as well as combustion of below-ground vegetation and organic soils, are releasing carbon dioxide and methane, which have shifted the Arctic tundra from a net carbon sink into a source.

In Asia, South Korea experienced it’s largest and deadliest wildfire on record in March 2025, with over 48,000 hectares (118,000 acres) burned and 28 fatalities reported. Meanwhile in the same month, Japan also suffered from its largest wildfire in over 30 years.

The UK: the latest wildfire hotspot

Wildfires are becoming a growing problem in the UK. By late April, 2025 had already broken the annual record of the highest area of land affected by wildfires since UK records began in 2011.

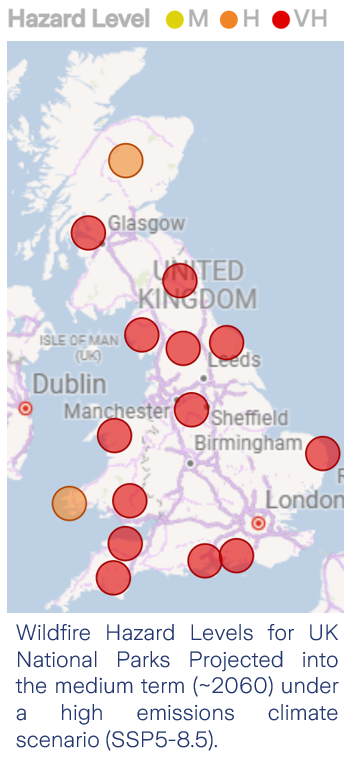

It’s a problem that is likely to intensify. According to climate data projections from Zurich Resilience Solutions, all 15 of the UK’s national parks (see map) will be at either a “high” or “very hazard” hazard level against wildfire by 2060 – based on the highest emissions scenario (IPCC scenario SSP5-8.5).

“The spring of 2025 has been the driest and one of the warmest in the UK this century, which has created ideal conditions for wildfires,” says Nicolien van Zwieten, Climate Risk Specialist at Zurich Resilience Solutions. “Flood and windstorms have historically been the two most common forms of extreme weather in the UK, but there is now an urgent need to address and adapt to the emerging threat of wildfire.”

What causes wildfires?

Three components are required for a wildfire:

- A heat source: This could be the sun, a bolt of lightning or a lit match.

- Fuel: This could be any flammable material, including dry grass, leaves and trees.

- Oxygen: Fire feeds off oxygen, which increases in high winds that also help spread the fire.

Wildfires occur naturally in many parts of the world and are an integral part of ecosystems. In Canada, just under half of all wildfires are caused by lightning – the other half are triggered by human activity, such as unattended campfires, discarded cigarettes, fallen powerlines and even intentional acts of arson. In the U.S., human activity is estimated to be responsible for nearly 85 percent of wildfires. Prescribed fires (also known as controlled burns), which are set intentionally to reduce the risk of extreme wildfires, can also become uncontrollable.

Types of wildfires

There are three main categories of wildfire:

- Surface fires: These burn in dead or dry vegetation, such as parched grass or fallen leaves and branches at ground level. They can burn fiercely and spread quickly with long flames.

- Crown fires: Occurring during hot and dry summers, these fires burn through the top layer of foliage on trees or tall shrubs. They are less frequent but far more dangerous, being the most intense and difficult to control.

- Ground fires: These ignite within peat or soil, feeding off organic material like plant roots and smoldering until they grow into a surface or crown fire. Smoldering peat fires are hard to extinguish and can rekindle frequently.

The term “wildfire” has widely replaced “forest fire” as common terminology for wildland fires. However, “forest fire” can be useful in distinguishing fires in woodlands from those in grasslands or shrublands. Fires in grasslands and shrublands are often called “brush fires,” not to be confused with “bushfire,” the common term for woodland and grassland wildfires in Australia.

Zurich Resilience Solutions

Managing risk. Unlocking opportunity.

Our Climate Resilience experts help you identify and manage climate risks, and prepare you for climate reporting.